Empirical SCOTUS: If Ginsburg leaves, it could be the liberals’ biggest loss yet – A look back at previous justices replaced with more conservative successors

The saga over Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s health seems to ebb and flow from the headlines almost daily. Part of the mystery relates to the amount of information shared with the public. We know that, while treating Ginsburg for rib fractures, doctors found malignant lesions in her lungs that were promptly removed, and that subsequent tests have shown no evidence of any other cancer. Ginsburg has since missed oral arguments and is reportedly recovering at home while keeping current with the court’s business through reading briefs and written transcripts of oral arguments.

Any major health scare for Ginsburg at 85 is a concern, and she is not out of the woods yet. Meanwhile news outlets such as Politico have reported that the White House is looking for potential replacements if the justice cannot continue on the court. Much of the future direction of the court rests on Ginsburg’s health, as a Trump appointment to her seat would almost certainly lead to the most conservative Supreme Court in recent memory.

Members of the public appear aware of the uncertainty surrounding Ginsburg’s health, even with the reassurances that she is cancer-free. I recently posted on Twitter a poll that asked what will happen to Ginsburg’s seat on the court depending on President Donald Trump’s length of time in office. The poll asked if respondents thought Trump would remain in office for one or two terms and whether Ginsburg would remain in her seat for the length of Trump’s term(s) of office. Although the majority of respondents, 55 percent, think Trump will last one term and Ginsburg will remain in her seat throughout the term, a not insignificant minority, 22 percent, feel Ginsburg will not remain in her seat even if Trump is only a single-term president. The other 22 percent of respondents think Trump will be re-elected to a second term, with 86 percent of this group thinking that Ginsburg would not last through a second Trump term. Only three percent of total voters think Ginsburg would retain her seat through a second Trump term.

The results of this poll express a mix of expectations that chiefly appear to depend on whether Trump is re-elected. Many political commentators including those on the left were aware of Ginsburg’s potential frailty leading up to the last presidential election and pressed her to retire in time for President Barack Obama to fill her seat with a younger justice. Commentators have followed up on these observations following Ginsburg’s most recent health concerns. However, given Chief Judge Merrick Garland’s unsuccessful nomination, Ginsburg’s decision seems more justifiable because the confirmation of a successor appointed by Obama might not have been guaranteed.

Why is this seat more important than Scalia’s or Kennedy’s?

If Trump fills Ginsburg’s seat, it will be the first time this president has the opportunity to shift a seat on the court from a strong liberal to a staunch conservative. Although such a shift has happened before, it is at best debatable whether it has happened on such an already conservative court. Let’s take a look.

Marshall to Thomas

The only comparable ideological shift occurred when Justice Thurgood Marshall stepped down from the court and Justice Clarence Thomas replaced him. The polarity of difference in these justices’ views cannot be overstated. Marshall was a pillar of liberalism in the Warren and Burger Court years, while Thomas has been arguably the most conservative justice of this generation. This difference is measurable as well. A justice’s vote can be viewed as most consequential when it shifts the outcome of a decision. We see this in cases decided by one vote, in which a shifted vote would switch the outcome from one side to the other.

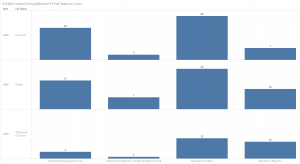

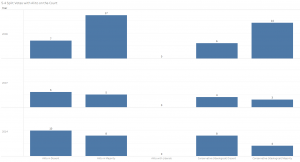

First a look at these closely decided cases from Marshall’s last years on the court:

The figure only looks at 5-4 decisions in these three terms. The first column shows the number of 5-4 decisions in which the court’s liberal minority, at that time Marshall and Justices William Brennan, Harry Blackmun and John Paul Stevens, formed a bloc in dissent. (When Brennan retired in 1990, the fourth most liberal justice on the court was likely Justice Byron White, who was a swing vote for liberals in prior terms.) The next column shows the number of times the liberal bloc was in the majority with the aid of the most common swing vote (The one observation in 1990 involved both White and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor siding with the liberals.). The third column shows the number of times Marshall was in dissent in 5-4 decisions in each of these terms and the fourth column shows the number of times Marshall was in the majority in 5-4 decisions in these terms.

Marshall’s votes had more than a theoretical impact on the course of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence late in his career. In 1989, Marshall had a key vote in the County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union decision. Marshall voted alongside Blackmun, Brennan, Stevens and O’Connor to hold that a creche inside a courthouse was an endorsement of Christianity in violation of the establishment clause. In 1987, Marshall was the deciding vote for the 5-4 majority in United States v. Paradise, which upheld against an equal protection clause challenge a state scheme that required the promotion of one black employee for every white employee. Such decisions would most likely have gone in the other direction without Marshall’s vote.

The liberal end of the court was clearly weaker after Brennan’s departure, although Justice David Souter, who joined in 1990 to fill Brennan’s seat, later turned out to be a consistent liberal vote. Still, overall Marshall was clearly in the minority in most of these close decisions toward the end of his tenure on the court. The important counterpoint is that if Thomas had sat in Marshall’s seat in these three terms, many if not most of the 5-4 decisions in which Marshall was in the majority would have shifted in the opposite direction.

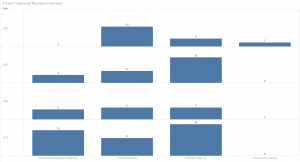

Some of this becomes evident when we look at comparative statistics for Thomas in 5-4 decisions.

Thomas didn’t come out of the gate with as clear of a conservative predilection as would become evident later in his tenure. In his first term he didn’t join the more conservative justices in any 5-4 decisions, while he sided twice with the four most liberal justices to shift the outcome in their favor in both cases. In his first term Thomas was also in dissent 10 times in 5-4 decisions while only in the majority in four such decisions.

This term marked the last time that Thomas was a swing vote for the court’s liberals, however. In the coming years Thomas would join with Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy, and O’Connor to form a strong, although not impenetrable, conservative majority. Thomas was in this ideological majority in 5-4 decisions four times in his second term, five times in his third, and 13 times in the 2000 term. Thomas tended to be in the majority of all 5-4 decisions more times after his first term and was in dissent less frequently.

Thomas’ votes had a substantial impact in close decisions in his first few years on the court. The court’s conservative majority (Thomas, Rehnquist, Scalia, White and Kennedy) in 1993’s Heller v. Doe held that under rational basis scrutiny, Kentucky’s procedures for involuntarily committing mentally retarded persons did not violate the equal protection clause. That outcome would have likely gone in the opposite direction with Marshall on the court instead of Thomas.

In another 1993 decision, Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School District, a 5-4 conservative majority composed of the same justices held that a school could not deny an interpreter to a deaf child based on the establishment clause. Under that ruling the state’s responsibility to provide an interpreter should not hinge on whether a school is religious or secular. The decisions described above only provide some context from Thomas’ first years on the court. Thomas would prove time and again to be an essential conservative component in closely decided cases.

O’Connor to Alito

O’Connor was nowhere near as predictable a liberal vote as was Marshall. To the contrary, O’Connor predominantly aligned herself with the court’s conservatives, but was more moderate than some of her conservative counterparts. Still, the shift from O’Connor to Justice Samuel Alito marked another significant move rightward for the court.

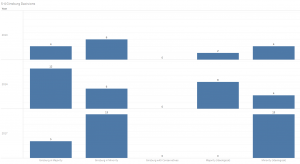

O’Connor’s importance to both ends of the ideological spectrum is evident from her last two terms on the court:

During these two terms O’Connor was much more often in the majority than in the minority in 5-4 decisions. Although she acted as the swing vote more often for the conservatives (Scalia, Rehnquist, Thomas and Kennedy), she was also the swing vote for the liberals — Stevens, Souter and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer — not an insubstantial number of times.

Without O’Connor’s vote in support of abortion’s legality, for instance, the court very well might have overturned Roe v. Wade with its decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. This was not the only landmark case that O’Connor helped decide with the liberals. In Grutter v. Bollinger, O’Connor wrote the majority opinion that was joined in full by Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg and Breyer, which upheld the University of Michigan Law School’s use of racial preferences in admissions decisions. O’Connor was also a swing vote for the liberals in McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union, in which the court held that displays of the Ten Commandments in public schools and courthouses violate the establishment clause.

In contrast to O’Connor’s votes joining the court’s liberals, Alito has never waffled between ideological poles in close cases.

Alito has still yet to side with the four more liberal justices on the court in a 5-4 decision. Half or more of his decisions in the 5-4 cases depicted above supported an ideologically conservative majority consisting also of Chief Justice John Roberts, Thomas, Kennedy, and either Scalia or Justice Neil Gorsuch. The vast majority of his dissents in 5-4 decisions were with the same grouping aside from Kennedy.

The impact of Alito’s coalitions is substantial as well. Early in his tenure on the court, Alito sided with the other conservative justices in Kansas v. Marsh upholding Kansas’ death penalty statute that would allow capital punishment in instances with equal mitigating and aggravating factors. Soon thereafter Alito also sided with the conservative majority in Gonzales v. Carhart, in which the 5-4 majority upheld the constitutionality of the partial-birth abortion ban. Although only applicable in limited instances, this ruling was seen as a significant step backward for pro-abortion-rights advocates.

Ginsburg

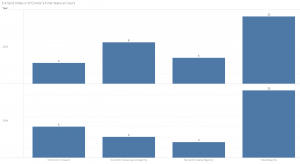

Similar to Marshall, Ginsburg has been one of the most consistent liberal votes on the court for many years. This is apparent in Ginsburg’s votes over the last several terms with a full nine-member court.

In these three terms there were no instances in which Ginsburg sided with the more conservative justices — Scalia/Gorsuch, Thomas, Alito and Roberts — in a 5-4 majority. Ginsburg was, however, in ideologically liberal majorities in many of her 5-4 decisions. The 2017 term was an anomaly for this, because Kennedy did not side with the court’s liberals in a single 5-4 decision. Consequently, every 5-4 decision in 2017 in which Ginsburg was in the minority (13 in total) involved a dissenting coalition with Breyer and Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Had a conservative justice filled Ginsburg’s seat over the past decade, the court might have gone in an entirely different direction. Some of the biggest liberal victories in cases such as Fisher II (affirmative action), Obergefell v. Hodges (same-sex marriage), Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (striking down a restrictive abortion law), and National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (health care) would have presumably gone in the other direction without Ginsburg’s vote. Based on this supposition, one can imagine the direction the court would move if a much more conservative justice filled Ginsburg’s seat.

How Trump might fill the seat

The most talked about candidate who was not nominated to fill Kennedy’s seat was most likely Judge Amy Coney Barrett. Even after Justice Brett Kavanaugh was nominated to the seat, news outlets (e.g., The Daily Beast and Washington Post) pointed out how Trump might have missed the mark with his pick. The time might be right for Trump to look to Barrett to fill Ginsburg’s seat if given the opportunity to do so. In this scenario Trump would have the opportunity to nominate a vocal Christian (Catholic) conservative who has under two years of experience as a federal court judge (on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit). With Barrett, Trump would not reduce the number of women on the court and would have a judge less exposed to many issues (and thus having a less clearly defined stake in them) than recent nominees Gorsuch and Kavanaugh.

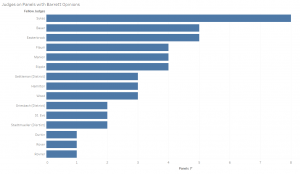

This limited judicial record could well work in her favor. She hasn’t sat on many high-visibility cases and so it is difficult to jurisprudentially connect her to certain positions on hot-button issues. Even with her somewhat limited experience, she seems to meet the model of a conservative Roberts Court judge with her votes. The figure below shows the types of parties Barrett has ruled for in decisions she has written as well as the issue areas under which these cases fall.

Barrett’s generally favorable approach to business and to the government is in sync with much of the Roberts Court’s decision-making. Still, a pro-government stance is much more difficult to discern from appeals court decisions, because cases at this court level are often less complex than the ones Supreme Court hears, and appellate court judges are more strictly bound by precedent than the justices. Suffice it to say, though, that her track record has few to no blemishes that would alarm conservative decisionmakers.

Barrett has also sat on panels with a mix of 7th Circuit judges and has generally met with little dissent in her authored decisions. The mix of other judges on panels for which Barrett was the majority author looks like the this:

Although Barrett’s counterparts on the court have mainly signed on to her opinions, two judges dissented in separate immigration decisions she wrote, for similar reasons. Judge Kenneth Francis Ripple dissented in the recent decision in Yafai v. Pompeo, and Judge Thomas Durkin, who was sitting on a panel by designation, dissented in last year’s Alvarenga-Flores v. Sessions. In both cases Barrett upheld immigration decisions that kept potential immigrants from the United States.

Barrett has dissented few times so far on the 7th Circuit. She has only written one dissent, in Schmidt v. Foster, a Sixth Amendment case dealing with the right to counsel.

Her viewpoint on abortion, however, has been brought into the spotlight both through a case decision and through her own writings. She is not bound to a judicial position on abortion, but she has divulged much more on this issue than most previous nominees. Barrett signed onto Judge Frank Easterbrook’s dissent from denial of rehearing en banc in Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. v. Commissioner of Indiana State Department of Health. The dissent examined two aspects of an abortion law, one of which would have “[made] it illegal to perform an abortion for the purpose of choosing the sex, race, or (dis)abilities of a child.” Easterbrook wrote:

Does the Constitution supply a right to evade regulation by choosing a child’s genetic makeup after conception, aborting any fetus whose genes show a likelihood that the child will be short, or nearsighted, or intellectually average, or lack perfect pitch—or be the “wrong” sex or race? [Planned Parenthood v.] Casey did not address that question.

Barrett’s pro-life position is made clearer in her own writings. In “Catholic Judges in Capital Cases,” Barrett, along with her co-author John Garvey, wrote: “In modern Catholic teaching, capital punishment is often condemned along with other practices whose point is the taking of life abortion, euthanasia, nuclear war, and murder itself.” They went on to say, “But a more precise statement of the church’s teaching requires a few qualifications. The prohibitions against abortion and euthanasia (properly defined) are absolute; those against war and capital punishment are not.”

Although Barrett’s writings do not necessitate an outcome in any particular case, they do put her prior position on this issue at odds with Ginsburg’s. If Barrett were to fill Ginsburg’s seat, we would see a very different court than we do today.

We can compare the extent of ideological shifts between Marshall and Thomas and between O’Connor and Alito to get a sense of the magnitude of a potential move from Ginsburg to Barrett. The figure below plots Martin-Quinn Ideological Scores, based the justices’ voting alignments, for the five justices just described.

Although a shift from Ginsburg to Barrett might not be as significant on a one-to-one level as the move from Marshall to Thomas, the overall impact on the court could be much greater.

Even with Ginsburg, the court’s left-leaning justices are outnumbered by those on the right. If the Supreme Court’s most veteran, leading liberal were to leave and be replaced by Barrett, the trajectory of the court, in terms of both case selection and adjudication, could very well look nothing like what we have seen in the past.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

* * *

Past cases linked to in this post:

Alvarenga-Flores v. Sessions, No. 17-2920 (7th Cir. Aug. 28, 2018)

County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union, 492 U.S. 573 (1989)

Fisher v. Univ. of Tex. at Austin, 136 S. Ct. 2198 (2016)

Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007)

Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003)

Heller v. Doe, 509 U.S. 312 (1993)

Kansas v. Marsh, 548 U.S. 163 (2006)

McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union, 545 U.S. 844 (2005)

Nat’l Fed’n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius, 132 S. Ct. 2566 (2012)

Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584 (2015)

Planned Parenthood of Ind. & Ky., Inc. v. Comm’r of the Ind. State Dep’t of Health, 896 F.3d 809 (7th Cir. 2018)

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992)

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973)

Schmidt v. Foster, 891 F.3d 302 (7th Cir. 2018)

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987)

Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 136 S. Ct. 2292 (2016)

Yafai v. Pompeo, No. 18-1205 (7th Cir. Jan. 4, 2019)

Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills School Dist, 509 U.S. 1 (1993)

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS