Empirical SCOTUS: The heightened importance of the Federal Circuit

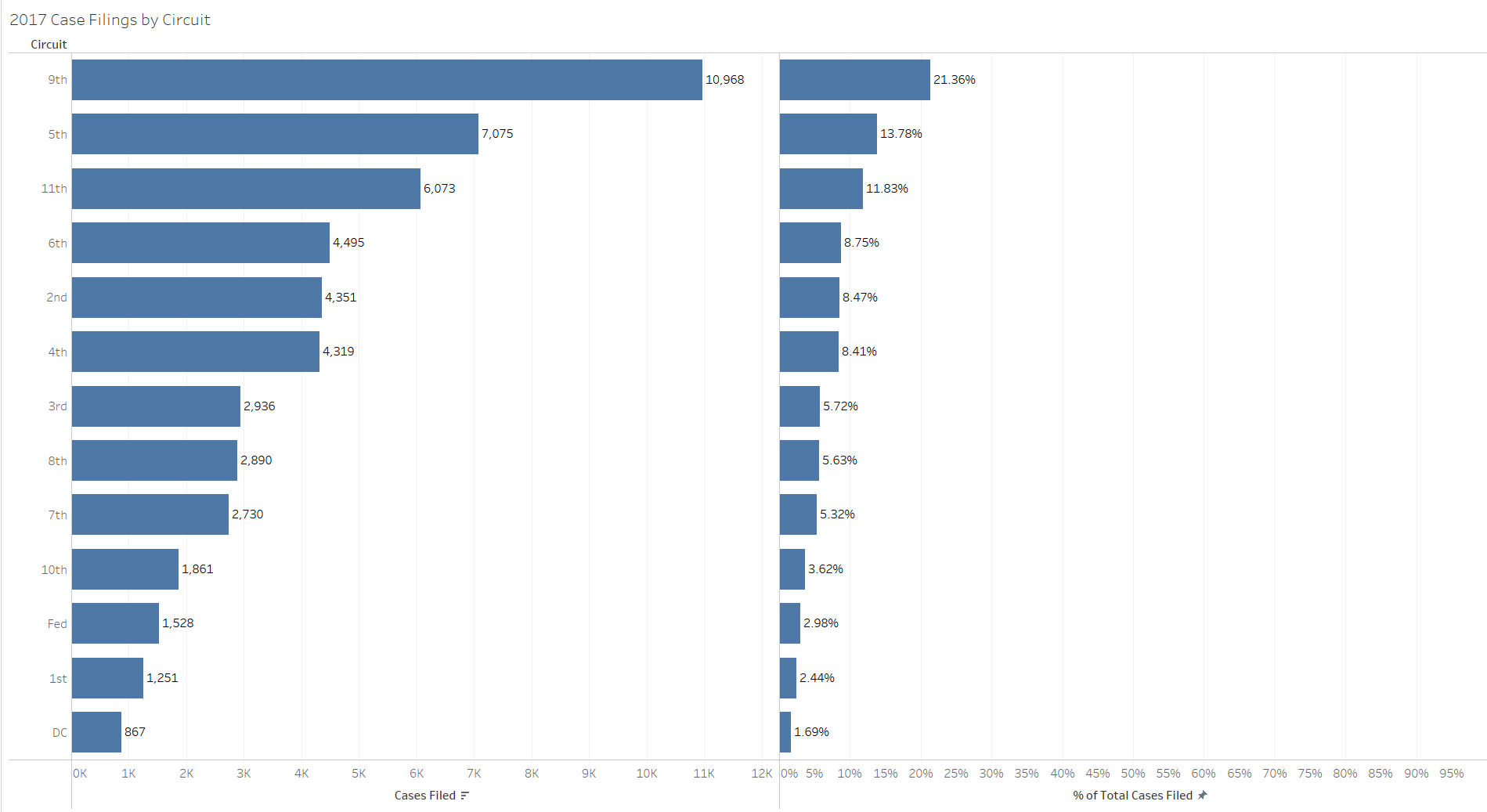

This term, the Supreme Court will hear argument in its 100th case decided below by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The Supreme Court’s recent grant of Kisor v. Wilkie also marks the fourth case granted from the Federal Circuit this term. This is by no means a small fraction of the Supreme Court’s total caseload. In terms of federal courts of appeals, the Supreme Court has only granted more cases this term from the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the 2nd, 6th, 9th and 11th Circuits. When we look at the number of cases filed in these courts, though, the Federal Circuit’s filings make up less than three percent of the total filings across the appeals circuits.

Why so much hubbub from the Federal Circuit? The circuit’s website explains how it differs from other appeals circuits both in the types of cases it hears and in the breadth of courts below from which it takes appeals. In terms of case type, the circuit has nationwide jurisdiction on a range of issues including international trade, government contracts, patents, trademarks, certain money claims against the United States government, federal personnel, veterans’ benefits and public-safety-officers’ benefits claims. (The recent glut of patent cases was the subject of a previous Empirical SCOTUS post.) It hears cases that were tried below from a variety of sources much more diverse than just federal district courts. As cases in these areas often have nationwide applications and require resolution on a national scale, the Supreme Court has taken an increasing number (both in quantity and as a fraction of the court’s merits docket) over time.

In 2018, the Federal Circuit took cases from 12 different types of lower courts (with federal district courts aggregated as one court type), as is displayed below:

Although the most cases came from the Patent and Trademark Office, a considerable number came from other sources like the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, Merit Systems Protection Board, and U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims. Two of the four cases on the Supreme Court’s merits docket from the Federal Circuit this term were initially heard by the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims.

When we look at the fraction of cases from the Federal Circuit on the Supreme Court’s merits docket since the Federal Circuit was established in 1982, we see this fraction slowly increase over time and more so in recent years.

In the figure above, each dotted line represents the trend of docket percentage for a federal appeals circuit. The green dotted line marks the Federal Circuit’s trend. While the federal circuit’s line slope is increasing in this graph, many of the other circuits’ trajectories are flat or declining.

Federal Circuit cases composed the largest percentage of the Supreme Court’s merits docket of federal appeals court cases (compared to the Federal Circuit’s relative percentage of cases in other years) in the 2016 term, with over 14 percent. Enthusiasts seeking to have cases heard by the Supreme Court might take heed of the relative likelihood that the court will take a case from the Federal Circuit compared to the likelihood that the court takes a case from any of the other circuits.

Over time, the list of courts that heard cases later appealed to the Federal Circuit and then to the Supreme Court are:

As the graph above with data provided by the Supreme Court Database shows, the most cases came from the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, but a not insignificant number were already tried once by the Federal Circuit on their way to the Supreme Court.

Focusing on the cases from the current term, the Kisor case is drawing considerable attention from administrative law experts, because it examines courts’ deference to administrative agencies’ interpretations of their own ambiguous statutes. In Gray v. Wilkie, the court will similarly look at whether the Federal Circuit has the authority to review an interpretation by the Department of Veteran Affairs of its own regulation. The other two cases from the Federal Circuit that the court will hear this term are Return Mail Inc. v. U.S. Postal Service, in which the court will decide whether the government should be defined as a “person” who can petition for review proceedings under the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, and Helsinn Healthcare S.A. v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA Inc., which asks: “Whether, under the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, an inventor’s sale of an invention to a third party that is obligated to keep the invention confidential qualifies as prior art for purposes of determining the patentability of the invention.”

Because the subject matter of cases before the Federal Circuit tends to be fairly specific, certain lawyers have gravitated toward arguing these cases on appeal. In many instances, Supreme Court experts like Carter Phillips and Seth Waxman take cases argued by other attorneys in the Federal Circuit. The attorneys who have argued the most Federal Circuit cases that later made their way to the Supreme Court are shown below:

This list is quite different from the one showcasing the attorneys who argued the most cases before the Supreme Court that were argued below before the Federal Circuit (arguing amici were removed):

[Note: Kannon Shanmugam’s second argument in this set of cases was in the recently argued Helsinn Healthcare case.]

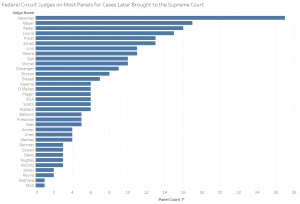

Equally important in understanding the dynamics between the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court is an assessment of the roles that Federal Circuit judges play in this system. Because the Federal Circuit is less than 40 years old, the number of judges who have sat on this court is small relative to most other appeals circuits. Several Federal Circuit judges have adjudicated substantially more cases that were later decided by the Supreme Court than others.

Judge Pauline Newman sat on far more of these panels than other judges, with 27. After Newman, the next several judges are tightly packed together: Judge Haldane Mayer sat on 17 of these panels, Judge Randall Rader on 16 and Judge Alan Lourie on 15.

Although Newman was present on the most such panels, she was not the most overturned majority author of the bunch. When we look at Federal Circuit majority decisions that were either vacated or reversed by the Supreme Court, the list of majority authors and number of times overturned is as follows:

Lourie and Rader, the two judges who sat on the most panels in cases later decided by the Supreme Court after Newman, had the most overturned majority decisions, with five each. They are followed by Mayer and Judges Arthur Gajarsa and Sharon Prost, with four apiece. Newman comes in next, with only three majority opinions later overturned by the Supreme Court.

An indication of the most prominent judges shifts when we look at those whose dissents were in cases later overturned by the Supreme Court, as shown below. (Virginia Hettinger, Stefanie Lindquist and Wendy Martinek give a detailed account of the strategic signaling effect of dissents in the federal courts of appeals in their 2004 AJPS article.)

Newman dominates this area with more than twice as many dissents leading to overturned decisions as the next set of judges on the list. Aside from the top five judges on the list, all other Federal Circuit judges have at most one dissent in a case later overturned by the Supreme Court. The disparate impact of certain judges’ dissents in this area re-emphasizes the strategic nature of such dissenting behavior and reinforces the sense that Supreme Court justices take heed of such signals.

Just as Federal Circuit judges have differential relationships with Supreme Court outcomes, so too do Supreme Court justices have differential relationships with this set of cases. The figure below shows the Supreme Court’s resolution of Federal Circuit cases by majority opinion author.

Justice Clarence Thomas, who with 15 has had more majority opinions in this set of cases than any of the other justices, also leads in reversals with eight. Justices Stephen Breyer and Thurgood Marshall have the next most with five each, while Justice Antonin Scalia leads in decisions vacating the lower court’s rulings with four. Justice David Souter, who with 10 has the second most majority opinions in this set of cases after Thomas, leads in affirmances with six, or more than half of his majority decisions in these cases. Thomas comes in next with five, although his ratio of reversals to affirmances is much more reversal-heavy.

The data above show that the Supreme Court is becoming keener on taking on cases previously heard by the Federal Circuit. In all likelihood this relates to the subject matter, national importance and scope of the issues involved in these cases, as well as the cases’ economic implications. The importance of this court is therefore unlikely to wane in the near future. The relationship between cases, attorneys and judges helps with outcome prediction both at the Federal Circuit and Supreme Court levels. Understanding feedback loops between players in these cases is key in forecasting how such cases may be resolved, and should remain so as long as the attorneys advocating and judges deciding in these cases stay largely the same.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.

Posted in Empirical SCOTUS