SCOTUS for law students: Justice William Brennan and Supreme Court avoidance

on Nov 21, 2018 at 2:59 pm

Even before Justice Brett Kavanaugh replaced Justice Anthony Kennedy this fall, some commentators were suggesting that liberals might want to avoid appealing cases to the increasingly conservative Supreme Court.

“If you are liberal,” wrote Ian Millhiser of the Center for American Progress in 2014, “you should probably try to keep your case away from the justices.”

With the appointment of Kavanaugh and the expectation that the majority will be more conservative, the idea of Supreme Court avoidance may take on even more currency.

Supreme Court avoidance could mean different things. It might mean seeking legislative solutions to issues in lieu of litigation or pursuing rulemaking approaches. In the context of this column, Supreme Court avoidance means turning to state courts and state constitutions to vindicate individual rights instead of relying on federal courts and the Supreme Court.

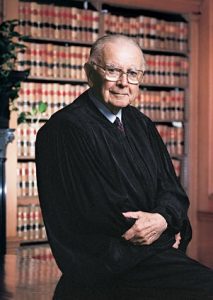

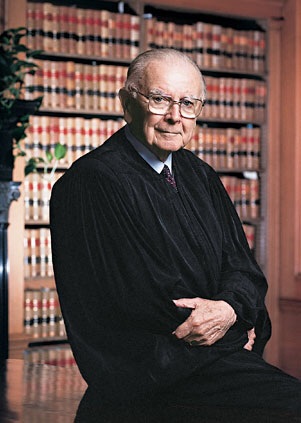

What kind of currency has this idea had in the past? To answer that question, it is helpful to turn the clock back more than 40 years to a little-noticed speech by the late Justice William J. Brennan Jr., which subsequently became hugely influential when it appeared in the Harvard Law Review.

In May 1976, Brennan was scheduled to be the featured speaker at the annual convention of the New Jersey Bar Association. Brennan hailed from New Jersey and was being honored by his home state bar for his 70th birthday and for the milestone of 20 years on the court. The location of the event was just one of the strange aspects of the occasion. The bar convention was held at the Playboy Great Gorge Resort in Vernon, New Jersey, once a luxury facility and now long since defunct. There was so much partying and there were so many speakers that Saturday night that when Brennan began to deliver his speech, few in the audience were listening. Brennan decided to cut short the talk so that the revelers could continue their festivities.

What the audience missed that night was a call to arms for lawyers to make more use of state court systems and state constitutions to protect civil rights and civil liberties. The reason for this clarion call was that, in Brennan’s view, the Supreme Court was becoming less sympathetic to claims of rights and would grow more reluctant to protect, let alone expand, rights.

When you have a hard time getting the attention of a live audience, it helps to be a Supreme Court justice with law clerks who previously served as editors of the Harvard Law Review. Brennan’s truncated speech appeared in full length some six months later in the January 1977 issue of the Harvard Law Review, entitled “State Constitutions and the Protection of Individual Rights.”

Noting that Supreme Court interpretation of the U.S. Constitution had expanded protection for individual rights in both federal and state courts, Brennan said that “state courts cannot rest when they have afforded their citizens the full protections of the federal Constitution.” He continued, “State constitutions, too, are a font of individual liberties, their protections often extending beyond those required by the Supreme Court’s interpretation of federal law.”

Brennan’s message was a pointed one. In the decisions of the 1960s, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren expanded a range of rights and liberties and recognized new ones. But by the mid-1970s, under Chief Justice Warren Burger, the expansion and recognition of new rights under the U.S. Constitution had slowed, and a more conservative majority was looking for opportunities to contract some of the past decisions.

In light of this directional change, Brennan said, “more and more state courts are construing state constitutional counterparts of provisions of the Bill of Rights as guaranteeing citizens of their states even more protection than the federal provisions, even those identically phrased.”

How does this concept work? The idea is that the Supreme Court’s interpretation of rights under the U.S. Constitution acts as a floor, not a ceiling. A state court may not interpret its own constitution to provide less protection than the U.S. Constitution because that ruling would then violate the federal level of protection. But a state court may provide more protection than the federal level because that typically does not clash with the U.S. Constitution.

Consider an example. The Supreme Court says the U.S. Constitution requires that criminal suspects who are in custody and who are being interrogated must be informed of their right to counsel and to avoid incriminating themselves – the famous Miranda warnings. A state interpreting its own constitution would violate the federal standards if it ruled that state law requires no warnings; federal rights prevail as the operative standard in that instance. But if a state court decided that suspects should be informed of their rights any time police have any contact with them at all, that expands rights and does not violate the U.S. Constitution, which sets a baseline.

To be clear, Brennan did not invent the idea of taking civil liberties issues to state courts and avoiding more conservative federal courts. Before he gave the speech in New Jersey, a handful of scholars and judges had reflected on the relationship between federal and state courts. One proponent was Judge Stanley Mosk, who served a remarkable 37 years on the California Supreme Court and used the idea of relying on expansive state-court rulings shortly before Brennan’s speech. Harvard Law School Professor Vern Countryman and University of Virginia Law School Professor A.E. Dick Howard had both written about state constitutions and state courts.

What Brennan did do was ignite a spark that became something of a movement in the late 1970s and into the 1980s. In the same year as publication of the Harvard Law Review article, a University of Oregon law professor, Hans Linde, was appointed to the Oregon Supreme Court. During his 23-year tenure, he became a leading proponent of state courts using their own constitutions to protect civil rights and liberties. Professor Robert F. Williams of Rutgers University Law School in Camden, New Jersey, caught the spark and has been a leading national expert on state courts and state constitutions for 35 years.

The relevance of this history to today’s Supreme Court dynamics should be apparent. Liberal civil rights and civil liberties groups have continued to bring their cases in federal court and to appeal to the Supreme Court largely because the justices were ideologically divided in some politically charged cases, with Kennedy offering the possibility of periodic 5-4 victories for the progressive wing of the court. But with Kennedy’s retirement, liberals have a diminished prospect of Supreme Court victories and may need to look elsewhere.

In theory this turn to state courts could be a conservative strategy, as well, not just a liberal one. It might be used, for example, to expand gun rights beyond the scope of the Supreme Court’s Second Amendment rulings. However, the last time there was a liberal Supreme Court majority that conservative litigants might have wanted to avoid, in the 1960s, state courts were much less active, and were being overridden by Supreme Court expansion of federal rights.

As a result, the idea of turning to state courts has been subjected to some criticism over the years by conservatives. Professor Earl Maltz, a Rutgers-Camden colleague of Williams, has been critical of the movement. Maltz has noted that Brennan framed the issue as one of federalism – recognizing that we have dual systems of government, state and federal, each entitled to respect for its distinctive role. But Maltz and others have argued that Brennan showed little interest in federalism or the role of the states until that approach would suddenly serve his own jurisprudential view in favor of expanding rights.

Whether liberal groups will actively decide to avoid the Supreme Court remains to be seen in the months ahead. If they do, the story of Brennan’s speech and article may serve as an historical roadmap.