Empirical SCOTUS: The strength of precedent is in the justices’ actions, not words

on Nov 28, 2018 at 2:11 pm

During his Supreme Court confirmation hearing in 2005, Chief Justice John Roberts declared, “Judges have to have the humility to recognize that they operate within a system of precedent shaped by other judges equally striving to live up to the judicial oath, and judges have to have modesty to be open in the decisional process to the considered views of their colleagues on the bench.” Although precedent is a strong principle in the justices’ decision calculi, it does not bind the Supreme Court in the manner that stare decisis functions for lower courts. This is apparent from Roberts’ decisions and from those of other justices. In the 2009 case Montejo v. Louisiana, the chief justice sided with a conservative majority led by Justice Antonin Scalia to overrule the Supreme Court’s prior decision in Michigan v. Jackson, which had held that evidence obtained through interrogation after the defendant invokes the right to counsel is inadmissible. Then in 2010 Roberts sided with another conservative majority, this time helmed by Justice Anthony Kennedy, in the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision overruling Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce and portions of McConnell v. FEC, which had upheld certain limits on campaign contributions.

Fast-forwarding to 2018, the issue of Roe v. Wade’s staying power was raised time and again during Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing. Responding to Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s questioning on the matter, Kavanaugh stated, “As a judge, it is an important precedent of the Supreme Court… I said that it’s settled as a precedent of the Supreme Court under stare decisis.” He later reinforced this statement by saying, “[Roe] has been reaffirmed many times over past 45 years.” These remarks were at odds with Kavanaugh’s previous statements while working as a White House attorney when he wrote, “I am not sure that all legal scholars refer to Roe as the settled law of the land at the Supreme Court level since Court can always overrule its precedent, and three current Justices on the Court would do so.” Kavanaugh’s expression of doubt regarding Roe’s staying power is actually an accurate depiction of Supreme Court precedent.

Although stare decisis binds lower courts to apply the Supreme Court’s precedent, the Supreme Court abides by a principle sometimes described as horizontal stare decisis, under which a precedent may be persuasive but is not binding (This concept is more often described when discussing precedents across various federal courts of appeal.). Potential Supreme Court nominee Judge Amy Coney Barrett described aspects of horizontal stare decisis in a 2003 article for Notre Dame Law Review. Suffice it to say, although Supreme Court decisions are far from tenuous, they have very little preclusive effect on the court’s decision-making and instead function as persuasive guidance.

Scholars have put forth several reasons for the Supreme Court’s overruling of precedent. One explanation by Professors James Spriggs and Thomas Hansford is ideological. According to these scholars, as a court moves ideologically away from a given precedent, it is more likely to overturn that decision. Professors Jeff Segal and Harold Spaeth offer a realist portrait, writing, “Overwhelmingly, Supreme Court justices are not influenced by landmark precedents with which they disagree.” Other studies, such as this one by Professors Ryan Black and James Spriggs, hypothesize that the value of precedent depreciates over time, allowing more room for the court to overrule older decisions.

Overruling precedent over time

Data from the Government Publishing Office, supplemented with decisions from the past two terms, show that the Supreme Court has explicitly or implicitly overturned over 300 of its decisions across its history. The rate of overturning has been nowhere near consistent across time. The court, for instance, was very wary of overturning any of its decisions early on. The first figure looks at the count of decisions the court overturned since its inception by term.

The big spikes are from around the Hughes/Stone Courts (1930-1946) through the Burger Court (1969-1986). The court had some of its highest decision-volume terms during these years, which, along with the court’s shifting perspectives on various rights enforced through constitutional amendments, helps explain a bit of this decision-making. Although the court’s rate of overturning its previous decisions did drop slightly during this period, the drop-off does not look as significant when the overturned decisions are examined as percent of the court’s total decision output per term.

In absolute terms, these counts of overturning decisions line up as expected by chief justice, with decisions under Chief Justice Warren Burger at the top followed by those under Chief Justice Earl Warren.

The staying power of precedent

When we look at how long the Supreme Court’s decisions last before they are overturned, this number has not extended over time. This is most likely a factor of decisions naturally aging as well as the justices deciding to discard older decisions that no longer make sense in the present context. The figure below shows the average amount of time by chief justice before decisions were overturned.

Although the chief justices do not perfectly order themselves in sequence from first to most recent, the three chiefs with the oldest precedents overturned on average during their tenures are the last three chiefs.

The histogram below shows the distribution of time that all decisions in this dataset lasted before they were overturned.

While the median age for overturned decisions is 18 years, the distribution actually extends from zero years — in several instances when the court reheard the same case in the same year — to 137 years, when Justice Thurgood Marshall authored the majority opinion in Exxon Corp. v. Central Gulf Line overturning Justice Robert Cooper Grier’s decision in Minturn v. Maynard.

The players

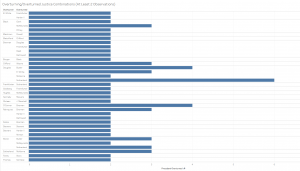

Some of the most interesting findings from this data relate to the justices who were most active in terms of overturning prior precedent. One caveat is that because the justices didn’t overturn many decisions in the Supreme Court’s early years, not many of those justices were active overturners. The justices are ordered below from those who overturned the most decisions to those who overturned the fewest.

Justices from the Warren and Burger Court years help comprise the top of this figure. Justice William O. Douglas, the most ideologically liberal justice since at least 1946, tops the list, as his decisions overturned 24 of the court’s prior precedents. Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justice William Brennan fill out the top three justices. While Rehnquist is at the top of this figure, it is interesting to note that Rehnquist’s successor as chief justice, Roberts, is at the bottom of this figure after overturning just one decision.

The justices at the top of the overturned list look quite different than those from the previous figure.

Justice George Sutherland, who sat on the court during most of the 1920s and 1930s, was the most often overturned of the justices, followed by Justice Felix Frankfurter, who joined the court soon after Sutherland departed, and by Brennan, who joined the court about 15 years after Frankfurter. Complicating the notion that older precedent is easier to overturn, we don’t arrive at a justice from the 19th century until the fifth in this figure, with Justice Joseph McKenna.

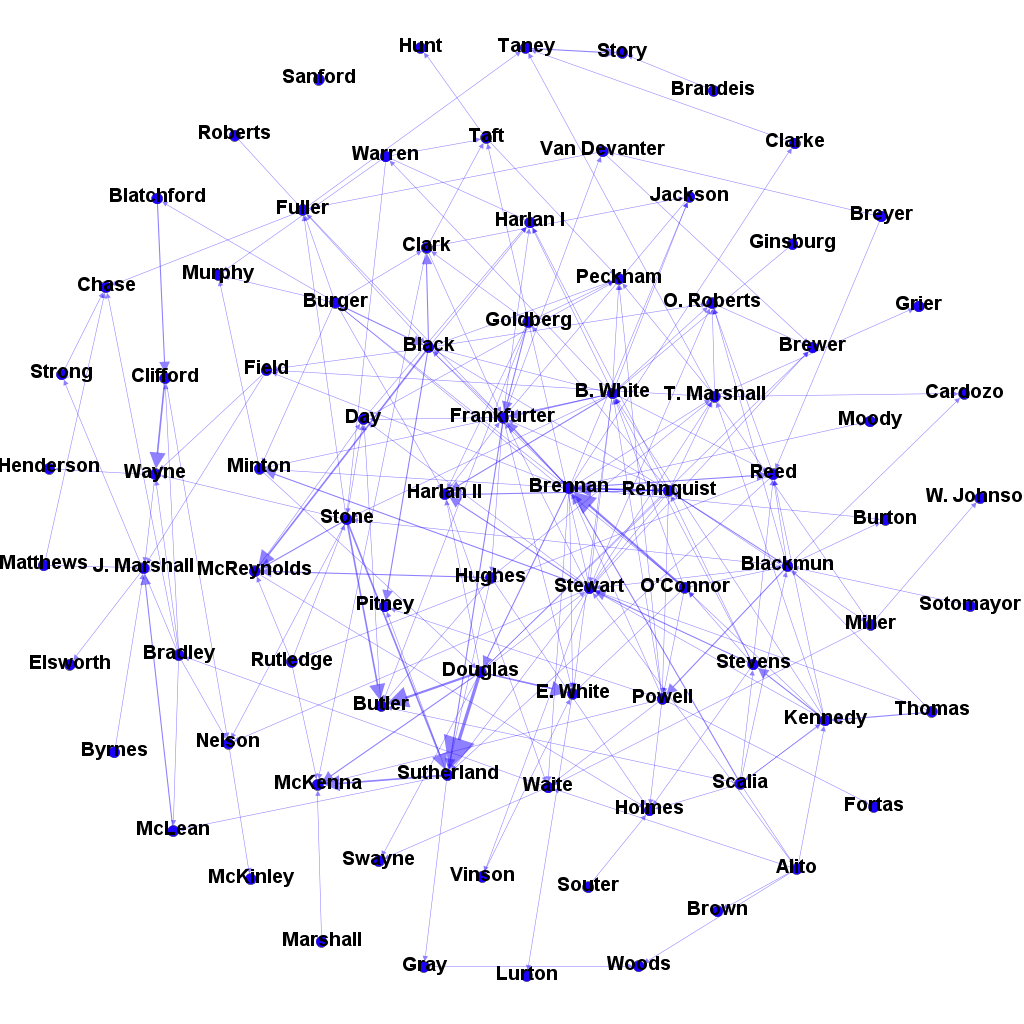

Several justices overturned certain justices multiple times. This series of justices follows neatly from the above data, with the most dominant combo being Douglas as overturner and Sutherland as overturnee. The figure only looks at combos with more than one decision overturned.

In terms of more modern justices of interest, Kennedy overturned multiple decisions authored by Justice John Paul Stevens; Justice Clarence Thomas overturned several of Kennedy’s decisions; and several justices, including Rehnquist and Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Antonin Scalia, overturned multiple decisions written by Brennan.

These relationships can also be used to construct an overturning case network of the most active justices. In the graph below, justices who both overturned decisions and had their own decisions overturned are packed toward the center. Justices less involved in such decisions are more toward the periphery. Directed arrows show relationships between overturner and overturnee and the size of an arrow depicts the magnitude of this relationship.

As the figure confirms, Brennan is close to the center, with other active justices, including Frankfurter, Justice John Marshall Harlan II, Rehnquist, and Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, also in the middle. The largest arrows correlate with the combo relationships described above, with the largest moving from Douglas to Sutherland and another sizable arrow moving from O’Connor to Brennan.

The Supreme Court has not slowed down in overturning its own precedent in recent terms. Just last term the court overruled four of its prior precedents with decisions in Janus v. American Federation, Trump v. Hawaii and South Dakota v. Wayfair. These data, however, do not lead to the inference that the court is especially likely to overturn particular decisions such as Roe v. Wade. The 322 overturned decisions in this dataset account for only a small fraction of the court’s total decision output over time. These data do show, though, that modern courts have been more likely than past courts to review and overturn prior decisions. This in turn means that the justices’ rhetoric about the importance of precedent is only as believable as their actions. In the coming terms the justices will inevitably overturn some of the court’s prior decisions. This doesn’t mean the court lacks respect for these decisions; some opinions may have become antiquated with the passage of time. It does mean that we should take a cautious approach when evaluating the likelihood that any decision has the power to stay on the books for a prolonged period of time. The justices have free rein in overturning their prior decisions and have exercised this right in varying degrees, especially in the past several decades.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.