Argument preview: Justices to turn again to rules for disestablishing tribal reservations

on Nov 20, 2018 at 1:20 pm

Carpenter v. Murphy has the Supreme Court once again reviewing the troubled history of the nation’s treatment of Native Americans. The specific question is whether the reservation once afforded the Creek Nation in what is now eastern Oklahoma remains a reservation for purposes of the Major Crimes Act. If it remains a reservation, then the state of Oklahoma was powerless to try Patrick Murphy for a murder he committed on that land in 1999, because the Major Crimes Act requires federal prosecution of certain major crimes committed on Indian reservations. If the land is no longer a reservation, then Oklahoma retains the authority to prosecute crimes in that territory.

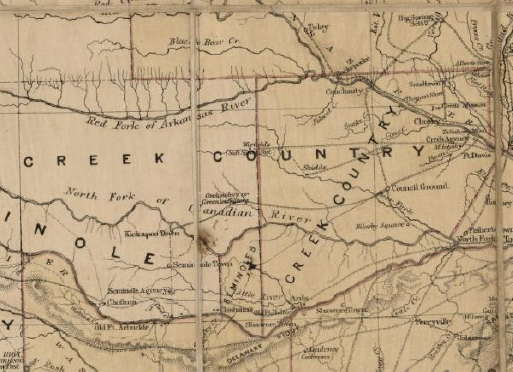

The backdrop of the case is one of the central incidents of the process by which Native Americans were removed from the Southeastern states in the early decades of the 19th century. The Creek Nation was one of the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes” forcibly relocated in the 1830s from Georgia, Alabama and Florida to a large Indian Territory that included what is now the eastern half of Oklahoma. At the time, Congress promised that the tribes would own their land “in fee simple,” meaning permanently and absolutely, that they never would be subjected to the laws of a state, and that their lands never would be made part of any state. But that of course is not how things turned out. In a series of statutes passed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Congress disestablished the tribal governments, transferred much of the land to federal control (for distribution to settlers — perhaps you recall learning about the Sooner land rush), and finally in 1907 incorporated all of the Indian Territory into the state of Oklahoma.

The case arises against a somewhat cluttered doctrinal background, under which the Supreme Court repeatedly has assessed whether land once set apart for Native Americans as reservations retains its reservation status. The problem is complicated because Congress often has taken title away from Native American tribes without removing the land from the reservation. Thus, the mere fact that the overwhelming majority of the Indian Territory has passed into the hands of settlers is not directly relevant. Generally speaking, the Supreme Court applies a test articulated in 1984 in Solem v. Bartlett, under which the court looks for language of “cession” — in which the tribe cedes the reservation land — or some other unambiguous evidence of disestablishment, as opposed to a simple transfer of land that did not remove land from the reservation.

As a doctrinal matter, the case is an interesting one, because it seems relatively clear that a straightforward and direct application of Solem would lead to a ruling in favor of Murphy. Although Congress passed numerous statutes retreating from (perhaps “breaching” is a better term) the various promises that it made to the Five Civilized Tribes, it does not appear that Congress ever adopted a statute in which the tribes ceded control of the reservation — in part because the tribes strenuously resisted the process by which Congress disestablished the tribal governments. As Murphy explains, the statutes did not reflect a “cession” of control because the tribes did not voluntarily agree to anything. Nor is there a statute in which Congress unambiguously stated that it was disestablishing the reservations previously promised to the tribes.

If Murphy’s side of the case is a straightforward doctrinal application of the Supreme Court’s existing cases, Oklahoma’s argument (petitioner Mike Carpenter is the warden of the Oklahoma State penitentiary in which Murphy resides) is a reality check. The opening pages of Carpenter’s brief include a map depicting the reservation that would result from a ruling for Murphy, which would cover about half of Oklahoma, including the entire city of Tulsa. Oklahoma argues that if the court rules for Murphy, Oklahoma would lose law-enforcement authority over the reservation — federal prosecutors would be responsible for prosecution of major crimes throughout the entire area. We know from the history that the federal government shifted law-enforcement authority to the state of Oklahoma immediately upon the state’s formation. A ruling in favor of Murphy would suggest, among other things, that all major prosecutions in eastern Oklahoma since 1907 were invalid as a violation of the Major Crimes Act.

That dichotomy sets up a nice template for assessing the argument. I’ll be watching to see how interested the Supreme Court is in adhering to the Solem framework in the face of the disruption it would cause to the long-settled expectations of state and local authorities.