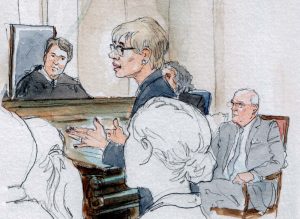

A “view” from the courtroom: Justice Kavanaugh takes the bench

on Oct 9, 2018 at 4:23 pm

Three days ago, demonstrators were literally storming the steps of the Supreme Court and clamoring at the bronze doors over the contentious confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh.

So today, with the now sworn-in Justice Kavanaugh ready to take the bench for the first time, there is an expectant air in the courtroom. Will there be the kind of protests that marked the main part of Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing in the Hart hearing room, or his final floor vote in the U.S. Senate?

To not bury the lead (for a change), the answer is no. There will be no interruptions during two hours of arguments.

It may have helped that the court appears to have removed the wooden chairs that are normally situated in the back of the courtroom, which are typically filled by rotating spectators from the “three-minute” line. It seems there is no three-minute line today.

At 9:45, Kavanaugh’s wife, Ashley, and their two daughters, Margaret and Liza, arrive and take seats in the second row of the guest box. Kavanaugh had indicated last night at his ceremonial oath-taking at the White House that the girls would be missing school today to observe the first two cases he would hear as a justice. Liza, the younger daughter, practically sinks below the top of the seatback in first row of bench seating in the guest section.

Kavanaugh’s parents, Everett and Martha, are in the first row of the public gallery, just across from the guest box.

A few minutes later, retired Justice Anthony Kennedy, whom Kavanaugh has succeeded, walks in while chatting with Martha-Ann Alito, the wife of Justice Samuel Alito. It is slightly jarring, of course, to see Kennedy in the courtroom for arguments without his judicial robe. He takes the first VIP chair in the row of such cushy chairs in front of the guest box.

When the court takes the bench, Kavanaugh is at his place on the far right (looking at the bench from the audience), next to Justice Elena Kagan. Barring unforeseen events, they will be next to each other for years to come, even as the justices rotate from one side of the chief justice’s seat to the other as vacancies among more senior members of the court arise.

Chief Justice John Roberts has a few words to mark this day.

“Before we commence the business of the court this morning, it gives me great pleasure, on behalf of myself and my colleagues, to welcome Justice Kavanaugh to the court,” Roberts says, adding that Kavanaugh has taken his oaths and his commission “will be duly recorded,” and the court will have a special sitting at a later time to mark the occasion.

“Justice Kavanaugh, we wish you a long and happy career in our common calling,” the chief justice says.

With Kennedy in the courtroom, Roberts says he would like to note the justice’s retirement. “At the appropriate time, we will in accordance with tradition and practice read and enter into the record an exchange of letters between the court and Justice Kennedy marking his retirement.”

During the routine of bar admissions, Kavanaugh takes his first sip of a beverage from an elegant silver cup, the type that seems to be issued to each justice even though they often prefer to have their favorite coffee mug at the bench.

From there, the court plunges into two arguments over the Armed Career Criminal Act, the federal statute that imposes a 15-year minimum sentence on any defendant who, having been convicted of three prior “violent felonies,” is found guilty of being in possession of a firearm.

In Stokeling v. United States, about whether a state robbery offense that includes “as an element” the common-law requirement of overcoming “victim resistance” is categorically a “violent felony” under the ACCA.

This argument has some moments that even young spectators seem to enjoy, such as when Roberts describes having his law clerks try to pull a dollar bill out of his hand while he held tight. (This was in response to an argument in the petitioner’s merits brief that “robbery can … occur where the offender does no more than grab cash from someone’s closed fist, tearing the bill without touching the person.”)

“It tears easily if you go like this,” Roberts says to Brenda Bryn, the lawyer for petitioner Denard Stokeling, motioning as if to tear a bill in half. “But if you’re really tugging on it … it requires a lot of force, more than you might think.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor asks about whether a “ordinary pinch” can involve sufficient force to break the law. And to demonstrate, she pinches her neighbor on her right, Justice Neil Gorsuch. At that moment, he is lifting his coffee mug for a sip, and his wide-eyed reaction to being pinched suggests a mix of bemusement and mild alarm.

Whenever a justice asks a question, Kavanaugh looks down the bench at his colleague. He sometimes dons his reading glasses, and he jots notes. We cannot see whether he has his trademark Sharpie marker.

At 10:25 a.m., Kavanaugh has his first question, asking Bryn about her arguments relating to a 2010 Supreme Court ACCA decision, Curtis Johnson v. United States.

“In Curtis Johnson, you rely heavily on the general statements of the court, but the application of those general statements was to something very specific: Battery and a mere tap on the shoulder,” Kavanaugh says to Bryn. “And all Curtis Johnson seemed to hold was that that was excluded. So why don’t we follow what Curtis Johnson seemed to do in applying those general statements to the specific statute at issue here and why wouldn’t that then encompass the Florida statute, which requires more than, say, a tap on the shoulder?”

In the second argument, for the consolidated cases of United States v. Stitt and United States v. Sims, the question is whether burglary of “a nonpermanent or mobile structure that is adapted or used for overnight accommodation can qualify as ‘burglary’” under the ACCA.

Kennedy apparently decides that one hour of argument about the ACCA is enough, and he slips out at the break between the two arguments.

The Stitt and Sims argument will lead to questions about cars with mattresses, homeless people living in their cars in New York and Washington, and unoccupied recreational vehicles and campers.

Alito tells Erica Ross, an assistant to the solicitor general arguing that burglary of an unoccupied mobile structure should count as a strike under the ACCA, that the court has “made one royal mess” of its interpretations of the federal statute.

Ross says that is something the court may need to think about in “some case,” but “I apologize … for continuing to bring us back to this case.”

This simple point really tickles Justice Clarence Thomas for some reason, and he laughs heartily for several seconds.

Kavanaugh asks more questions in this second argument, though he also loses a couple of what I call “faceoffs” — when two justices battle for the floor, continuing to speak until one relents. He defers to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg at one point, and to Kagan at another. (Although the rule of thumb is that a junior justice ought to defer to a senior colleague in such situations, that rule is not always observed.)

Kavanaugh will have several extended colloquies, appearing more at ease with each one. Several times, Jeffrey Fisher of Stanford Law School, the court-appointed lawyer for the respondents in the second case, begins his answer by saying, “Well, Justice Kavanaugh, …”

It is in those tiny moments that the reality sinks in that Brett Kavanaugh of Maryland is now an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.