Empirical SCOTUS: Will Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing provide any useful information?

on Sep 5, 2018 at 3:48 pm

Supreme Court nominees’ confirmation hearings involve much dialogue between nominees and senators. The dialogue, though, hardly ever provides substantive information about the nominees. In two chaotic days of the Senate Judiciary Commission’s hearing on the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh, we have seen a full spectrum of behavior from both sides of the aisle. Showboating aside, this is a genuinely important hearing for a crucial seat on the Supreme Court and hence emotions are running high. Although much of the discussion leading up to the hearing surrounded how nominees do not answer substantive questions, many still hope that this time around things may be different. As scholars Paul Collins and Lori Ringhand have shown in a series of articles (for example), much can be learned about what we can expect from studying past confirmation hearings.

This post crunches data from the transcripts of the past four confirmation hearings — those for Justices Neil Gorsuch, Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor and Samuel Alito– to see how senators’ speaking patterns and interactions with Supreme Court nominees shape the process. These four hearings are a nice mix because they showcase nominees from two Democratic and two Republican presidents. This analysis also shows how we can leverage more information from the transcripts than may be readily apparent from watching the hearings on TV.

The post looks at three main features from these hearings: the speech and interaction patterns, talking statistics and tone or sentiment of each speaker’s comments. The underlying data, which consists of several hundred transcript pages per nominee, includes senators’ opening remarks and interaction with the nominees, which were run through a package called qdap in R. The analysis ends before additional witnesses are called (Some witnesses are incorporated in the analysis, though, if they spoke on the first or second day of the hearings.).

Based on this analysis and the current state of politics, we can expect an even more polarized process than we have seen in previous hearings, in which it should be hardly recognizable that Democratic and Republican senators are speaking to the same nominee.

The post looks at these four nominees in chronological sequence based on the order in which they were nominated.

Alito

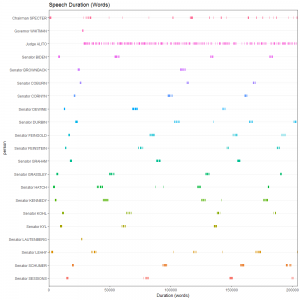

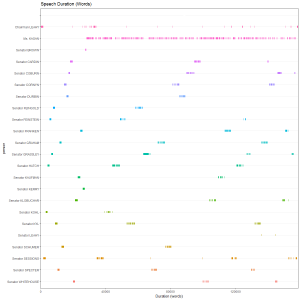

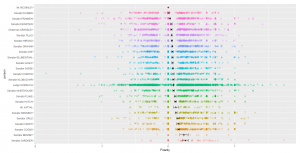

Graphs that track speech patterns look at the number of words spoken by each speaker and at the order of speakers. Moving sequentially through the nominees, we begin with Alito.

Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania presided over Alito’s hearing. As such, he (and all other chairpersons in these analyses) spoke the most of the senators present at the hearing. Senator Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and Senator Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., both took more opportunities to interject during the proceedings than their fellow senators.

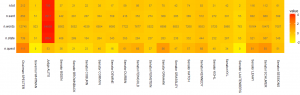

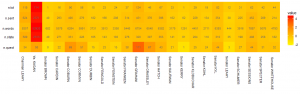

Breaking this down to the word statistics shows the amount of speech per senator. The row categories are n.tot for total utterances, n.sent for number of sentences, n.words for word count, n.state for statement count, and n.quest for question count.

In terms of amount of speech, an interesting pattern is clear from these hearings. After Specter, the chairperson, the next four most active speakers were Democrats Leahy, Chuck Schumer of New York, Russell Feingold of Wisconsin, and Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts. Schumer asked the most questions after Specter, followed by Senators Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Leahy. Schumer also had the most statements after the chairperson, followed by Leahy and Kennedy. Based on these statistics alone, we can see that the type and intensity of engagement differs between Republicans and Democrats.

Especially because of the hyper-polarization of modern confirmation hearings, the amount of speech from a given senator says little about how he or she will vote. In this instance, all members of the Senate Judiciary Committee voted along party lines, with Republicans voting in support of Alito’s confirmation and Democrats voting against it.

How about the tone of the senators’ comments? Note that the sentiment dictionary is not law- or politics-specific and so it might not pick up on all of the linguistic nuances. It does provide a useful gauge of the relative tone of each senator’s comments, though. The scores range from +1 for a positive sentiment to -1 for a negative sentiment, with zero as neutral.

First of all, although all senators incorporate words with a negative sentiment into their speech, all of the average sentiments were at least neutral (which tends to be the case across nominees). This also shows, at least at first blush, that the senators’ parties did not lead to their ranking in terms of the relative positivity in their remarks. Although four Democrats — Leahy, Dick Durbin, D-Ill., Joe Biden, D-Del., and Schumer — ranked low on positive tone relative to other senators, so did two Republicans: Tom Coburn, R-Okla., (who had the lowest sentiment score) and Mike DeWine, R-Ohio. Although Democratic Senator Herb Kohl of Wisconsin was not the most active speaker at the hearings, he had the most positive sentiment score of the senators followed by the chairperson, Specter. Senator Frank Lautenberg, D-N.J., did not sit on the Judiciary Committee.

Sotomayor

Leahy was the chairperson for Sotomayor’s hearing. He spoke the most of the senators, as is evident in the figure below.

Senator Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., took the most interaction turns with Sotomayor, although many senators took multiple speaking opportunities during the hearing. The word statistic data further bears this out.

Following the pattern of Alito’s hearings, after the chairperson, Leahy, eight Republicans spoke more actively than the most active Democrat, Feingold (Feingold spoke 1,000 fewer words than Specter, who was the next most active speaker.). Graham, Hatch, Coburn and John Cornyn of Texas, all Republicans, asked the most questions at these hearings. Clearly, members of the opposing party from the nominating president were more active at the hearings so far reviewed in this post.

Although most senators on the Judiciary Committee voted along party lines as they did in Alito’s case, Graham, the most active speaking Republican senator, voted in support of Sotomayor’s confirmation.

The senators’ relative sentiments were more predictable along party lines in these hearings than in Alito’s.

As with the Alito hearings, the speakers’ sentiments in Sotomayor’s hearings were neutral to positive. The eight most positive senators in Sotomayor’s hearings were Democrats. Although Durbin ranked most negative in sentiment, the next six most negative sentiments were all from Republican senators, with Senator Jon Kyl of Arizona as the next most negative after Durbin.

Kagan

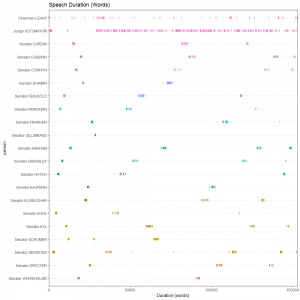

The speech patterns from Sotomayor’s hearing were similar to those in Kagan’s hearing.

Leahy once again was the most active senator speaking. Sessions once again was one of the most active speakers as well.

As with Sotomayor’s hearing, at Kagan’s hearing the most active speakers after the chairperson were Republican senators.

In terms of overall speech, after the chairperson, seven Republicans spoke more words and on more occasions than the most active Democratic senator. Graham had far more questions than any other senator, followed by fellow-Republican senators Grassley and Coburn. Again, Graham was the only Republican member of the Judiciary Committee to break with his party and vote in support of Kagan’s confirmation. Graham also had the most questions for Kagan.

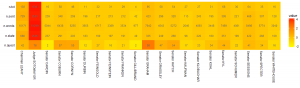

The senators’ sentiment scores for Kagan’s hearings were somewhere in between those for Alito and Sotomayor.

The tones were mainly neutral to positive. Although the most negative sentiments were mainly from Republicans and the most positive were mainly from Democrats, there were a few anomalies. Four of the five most negative overall sentiments were from Republican senators, although Democratic Senator Al Franken of Minnesota had the second most negative sentiment score. Similarly, nine of the top 10 most positive sentiments were from Democrats.

Gorsuch

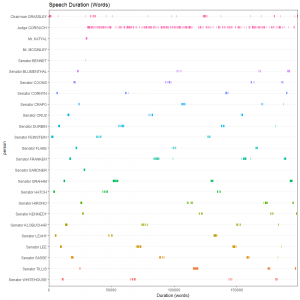

Grassley was the chairperson for the most recent hearing before Kavanaugh’s, and many senators who were present during Gorsuch’s hearings did not participate in the previous confirmation hearings.

These speech statistics include the opening remarks of Neal Katyal and the one line from then-White House Counsel Michael McGinley, which was “I never thought I would carry a bag after graduating law school.” The senators appear to have evenly engaged Gorsuch in the hearings, although some of the distinctions are made more evident through the word statistics.

After the proceedings’ chairperson, Grassley, four of the five most active speakers were Democrats, with Senators Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island topping this ranking. After those two senators, though, Senator John Kennedy, R-La., was the next most active speaking senator. The seven most reticent senators at the hearing were all Republicans. Blumenthal and Graham had the most questions for Gorsuch.

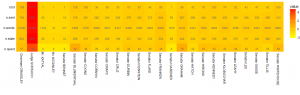

The sentiment scores were only somewhat useful in deciphering the senators’ views of Gorsuch.

Although the bottom three scoring senators were all Democrats (Durbin, Franken and Feinstein), the fourth lowest-scoring senator was Grassley. Further, when looking at the top-scoring members of the Judiciary Committee, Senator Chris Coons, D-Del., was atop the list and voted against Gorsuch. The next three highest-scoring senators, however, were all Republican (Ted Cruz of Texas, Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, and Kennedy) and all voted in support of Gorsuch’s confirmation.

What This Tells Us About Kavanaugh

Some patterns are clear from these four previous hearings, and we should expect similar output this time around.

- Members of the opposing party (to the nominating president) tend to have more to say. This includes the combination of opening remarks and discussion with the nominees.

- The senators differentially engage the nominees. Some take multiple opportunities throughout the hearings, while others speak mostly during their designated slots.

- Although members of the opposing party tend to ask more questions, this is not universally the case, as some senators are uniquely engaged in questioning the nominees.

- The sentiments or tone of the senators’ remarks are sometimes, but not always, telling of their party and how they will vote. Senators may grill Kavanaugh with questions without largely negative tones in their remarks. Sentiment, along with substance, provides more information on the senators’ positions, but sentiment alone does shed light on many senators’ views of the nominees.

- Polarization is really the name of the game. Party identification is the most telling piece of information on the senators’ past votes. Inevitably this facet will be more heightened this time around. Especially with the failed nomination of Judge Merrick Garland and the potential of this nomination to shift the ideological orientation of the court, we can expect party to play an even greater role in senators’ votes. Even if senators’ votes do not clearly represent all senators’ views of the nominee, senators are facing incredible pressure to vote along party lines, as one vote could tip the balance in favor or against Kavanaugh’s confirmation.

This post was first published at Empirical SCOTUS.