Empirical SCOTUS: Without a swing vote, it’s game over for the Democrats

on Aug 28, 2018 at 5:11 pm

The Democrats are in a precarious position in the latest battle for a seat on the Supreme Court. Many Democrats oppose Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination and will not vote to confirm him. Others are requesting that the Senate hold off on voting on Kavanaugh’s confirmation until the National Archives produces the record-setting million or so pages of documents from Kavanaugh’s work in the federal government. The Democrats’ strategy is twofold. First, if they can push the vote until after the midterm elections, they may gain a majority in the House, Senate or both, potentially giving them greater leverage over the confirmation process. Second, some of the documents, specifically those from when Kavanaugh worked in the White House counsel’s office under President George W. Bush, might paint a more contentious picture of Kavanaugh and one that makes him less characterizable as a confirmable candidate.

As several articles have pointed out though, the chances that the vote timing gets stretched past the midterm elections are incredibly slim, and stretching the timeline closer to the midterm elections might hurt Democrats running for office. Because the Democrats lack a majority of votes in the Senate, there is little they can do to slow the process set forth by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell aside from trying to sway potential swing Republican senators away from a pro-Kavanaugh vote (or to push for a vote past the midterms).

With a Republican majority in the Senate, convincing any Republican senators to oppose the vote as planned may be an impossible task. The vast majority of Republican senators have already declared support for Kavanaugh and are not viable options for persuasion. Even with the recent death of Sen. John McCain, in order to prevent an easy road for Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, the Democrats will have to sway at least one Republican senator either not to vote before the midterm elections or to vote against Kavanaugh’s confirmation.

Party-line voting

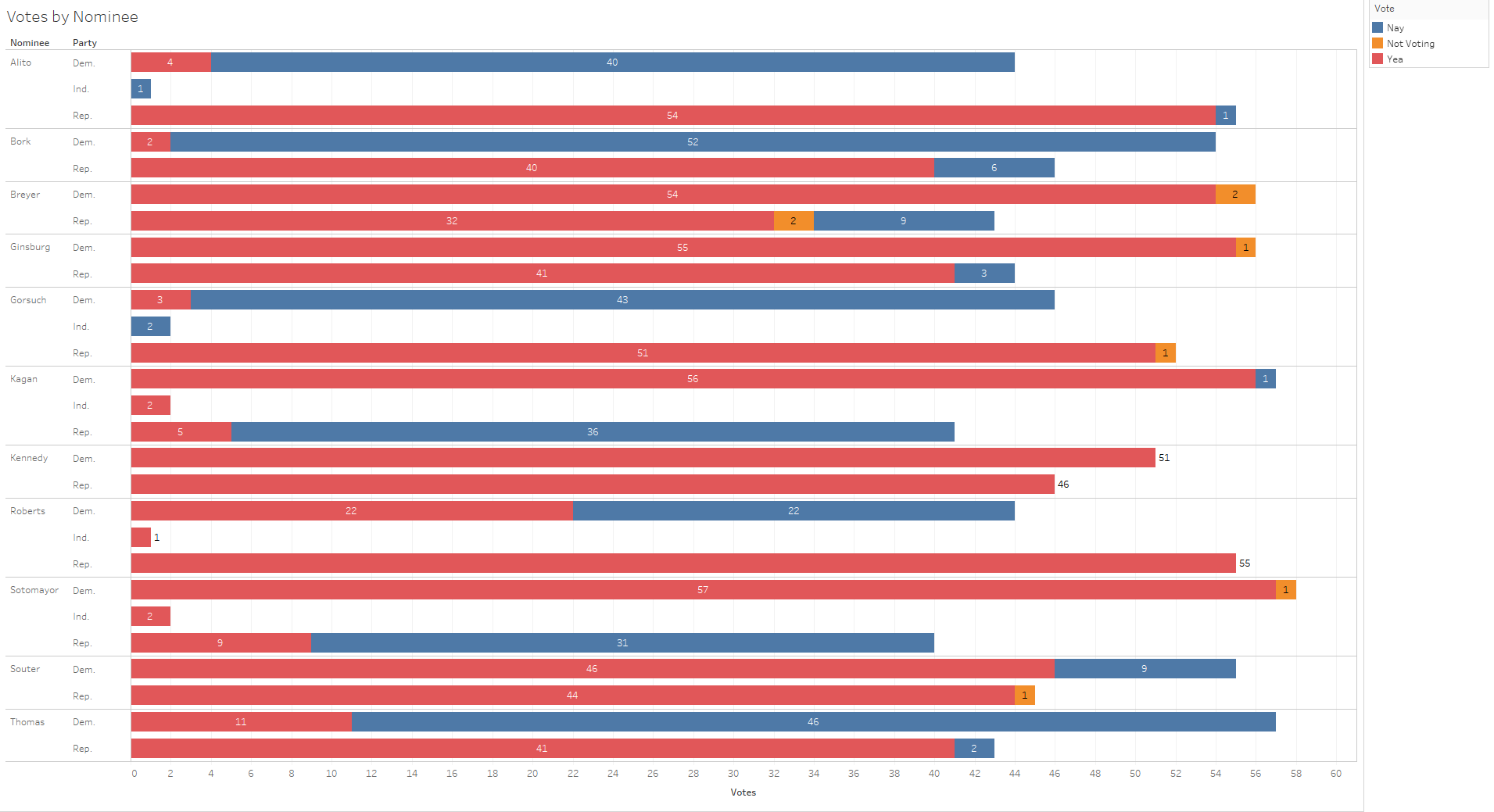

An additional problem for Democrats is that it seems more plausible that Democratic senators will flip and support Kavanaugh than that Republican senators will flip and vote against Kavanaugh. The last several Supreme Court confirmation votes help to shed some light on this. [Note: The data in this post go back to Judge Robert Bork’s failed confirmation in 1987.]

During Justice Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation, all voting Republicans voted in support of confirmation, along with three Democrats. During Justice Elena Kagan’s confirmation, one Democrat voted against Kagan, while five Republicans voted for her. For Justice Sonia Sotomayor, all voting Democrats along with nine Republicans voted in support of her confirmation. In fact, the Bork confirmation vote was the only instance in the figure when more senators of the nominating party voted against confirmation than members of the opposing party voted for confirmation. This spotlights the battle Democrats face in attempting to persuade more Republican senators to flip than the other way around. (It is also worth noting that Kennedy was the last justice to be confirmed by a unanimous vote.)

These data can be parsed somewhat differently when senators are separated by state. This figure helps us look at the consistency of party-line votes by senators’ states and parties.

Because we know that Democratic senators from North Dakota (Sen. Heidi Heitkamp), West Virginia (Sen. Joe Manchin), and Indiana (Sen. Joe Donnelly) voted in support of Gorsuch’s confirmation, and they are perceived as possible votes for Kavanaugh this time around, they seem like good places to start.

West Virginian senators have been predominantly Democratic since the Bork nomination. One West Virginian Democratic senator voted in support of Justice Samuel Alito’s confirmation (Robert Byrd), while both Byrd and Democratic Sen. Jay Rockefeller voted in favor of confirming Kennedy, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice David Souter. Indiana, on the other hand, has had predominantly Republican senators over this period. Republican senators from Indiana voted to confirm Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Kagan and Sotomayor. North Dakota senators, like their West Virginian counterparts, were primarily Democrats across this period. Along with Heitkamp’s vote for Gorsuch, both Democratic senators voted in favor of Roberts’ and Kennedy’s confirmations, while one Democrat voted in favor of Souter’s and Alito’s.

Ideology

Not all cross-party votes are equal though. One way that positions within parties can be located is through votes. Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal’s Voteview Project provides ideology scores (Nominate Scores) for all members of Congress across time based on their scaled roll call votes. Senators’ relative ideologies should help gauge the likelihood that they will vote for nominees across party lines, because senators of one party located closest to members of the opposing party theoretically share the largest set of preferences with those in the opposing party.

Poole and Rosenthal’s scores, which run from -1 to +1, go through the current 115th Congress. The landscape of the current senators’ scores is depicted below.

Not many senators sit close to the zero marker and only a handful are toward the ends of the liberal or conservative spectrum. None of the current Republican senators achieve a liberal score, nor do any Democratic senators achieve a conservative score.

We can focus these scores on those members of both parties who voted across party lines in favor of nominees since and including Bork.

Some nominees were able to garner cross-party votes from many senators. Looking at graphs for Justice Stephen Breyer, Ginsburg, Kennedy and Souter, we see large variation in the ideology scores of these senators. Focusing on other instances, however, such as the nominations of Alito, Justice Clarence Thomas, and even Bork, and to a lesser extent Kagan and Sotomayor, we see that most of the cross-party votes are relatively close ideologically to a moderate score of zero. All three Democratic senators who voted in support of Gorsuch – Manchin, Donnelly and Heitkamp — were also located toward the moderate end of the liberal spectrum.

While looking at these cross-party votes in isolation provides insight into these specific votes, additional context is provided by comparing these senators’ scores to those of the other senators who voted on the same confirmations. The figure below shows the relative ideology scores of all senators’ who voted on the nominees by their party and votes.

Here we see, as expected, that the cross-party votes in instances when there were only few such votes (as with Gorsuch) tend to be depicted in lighter blue and red hues than the average ideology scores for members of each party.

Swing votes

Based on several articles (such as these in Vox and in CNN) describing the senators’ positions on Kavanaugh, two to three Republican senators and seven or so Democratic senators’ votes are still undecided (The Vox article reports that both Independent senators are likely to vote against Kavanaugh’s confirmation.). When we place these senators on the Nominate Scale on independent axes we find the following ideological positions.

As a point of reference, the mean score for Democratic senators in the 115th Congress is -.336 and the mean score for Republican senators is .460. Focusing on the only way the Democrats can win — if at least one Republican senator votes against the nomination — three Republicans are in the discussion.

The first Republican, Sen. Jeff Flake, is quite conservative, and while he is known not to be a fan of Trump’s, he also has spoken words of high praise for Kavanaugh. There was speculation at one point that Flake might be out of the country at the time of the confirmation vote, but Flake has since clarified that he will be back by that time.

Sen. Susan Collins has also yet to express a firm position on Kavanaugh, and some speculated that she might be concerned about the possibility that Kavanaugh would vote to overturn the Supreme Court’s precedent Roe v. Wade. After she met with Kavanaugh, however, multiple outlets reported that she seemed mollified by Kavanaugh’s assertion that Roe is “settled law.”

Putting aside the question of how Kavanaugh would rule on Roe if faced with the possibility of overturning it, Collins should pause before accepting “settled law” as a barrier to Supreme Court adjudication. The following chart based on data collected from the Supreme Court Database plots the number of times each term that the court ruled a statute unconstitutional and the number of times the court overturned its own precedent. Both types of laws were “settled” prior to the court’s decisions.

As the court evolved, the justices clearly became more comfortable overturning “settled law.” Although this does not allow us to infer Kavanaugh’s position on Roe, it does at very least provide insight suggesting that the court is not bound to uphold “settled law” and that it has become increasingly comfortable with overturning precedent since the beginning of the 20th century.

The public’s views

Suffice it to say the path to Kavanaugh’s confirmation is clear. Though there are potential hurdles, there are no clear roadblocks. Alaskan Sen. Lisa Murkowski may be the Democrats’ last bastion of hope (and only if all Democrats vote against Kavanaugh). Murkowski put out a statement after meeting with Kavanaugh that does not clearly set forth a position. However, reports indicate her likely support.

One factor potentially working against Kavanaugh is public opinion. As the graph below shows, Kavanaugh has the lowest percentage of support for a nomination since Bork and has the second highest percentage of opinion, after Harriet Miers, not in favor of confirmation in the same period.

Public opinion only plays a role, though, if it affects senators’ votes. As senators seem increasingly polarized in their decisions on potential justices, public opinion may only have an impact, if any, at the margins.

As with the vote on Gorsuch’s confirmation, the new simple-majority requirement for a confirmation will likely play a role, as Republicans are unlikely to garner a supermajority vote. The bottom line for Democrats is that unless they can sway a Republican senator’s vote, they are likely out of options in opposing Kavanaugh’s confirmation. Although this is far from a done deal, it is clearly an uphill battle for Democrats.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.