SCOTUS for law students: Supreme Court mysteries and the justices’ papers (Corrected)

on Jul 2, 2018 at 1:19 pm

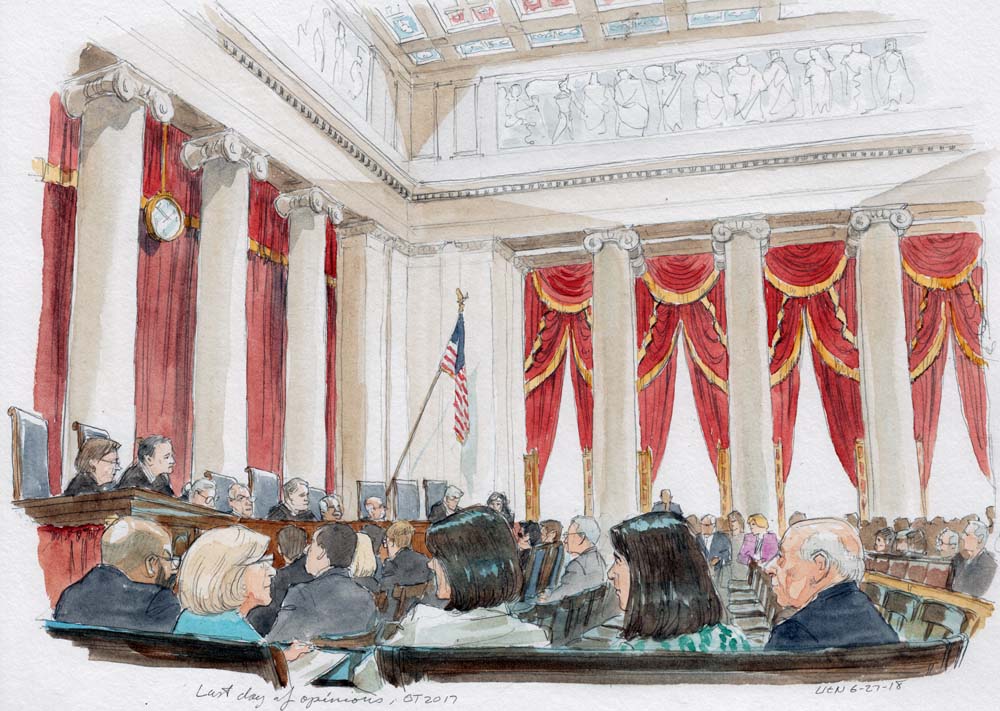

In the month of June, when the Supreme Court issues dozens of decisions to conclude its term, who would not want to be a fly on the wall inside the conference of the justices trying to understand what compromises were made or why cases came out as they did?

Rarely has this been more true than this past month, in which a seemingly large number of the court’s most closely watched cases produced decisions that decided much less than was anticipated by court-watchers and litigants.

What is one to do to satisfy curiosity about why, for example, the court yet again declined to confront questions about the constitutionality of political gerrymandering of legislative districts?

The short answer is wait. Wait for what, you ask? Often, the answers to nagging mysteries about what happened inside the court and why can only be answered by historians who some time in the future get to pore over the papers of justices who have long since retired or died.

How does this process work and what might one learn from the papers of the justices?

The first thing to know is that there is no uniformity of any kind among the justices and their files and records. Justices are free to save or destroy whatever records they choose, to donate them wherever they want, to make them available whenever they want and to include whatever content they like.

This thoroughly unregulated field is in marked contrast to the papers of presidents, which are governed by federal law. Under presidential records statutes, every piece of paper must be saved and preserved. The Supreme Court, however, has no such statute, and so it is up to each justice to decide what to do with his or her files.

What has this meant in recent decades? Justices have spread their papers around the country. The largest single repository of justices’ papers is the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, housed in the Madison Building in Washington, D.C. There, one can find the papers, among others, of Chief Justices Earl Warren, Fred Vinson, Harlan F. Stone and William Howard Taft, and Associate Justices William J. Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, Harry Blackmun, Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, Byron White, Arthur Goldberg and many more.

Among the most recent departures from the court, Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and John Paul Stevens have given their papers to the Library of Congress, but those collections remain closed until some future date specified by the individual justices. The papers of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in February 2016, have been donated to Harvard University and are closed. Justice David Souter, who left the court in 2009, donated his papers, which are closed to the public until 50 years after his death, to the New Hampshire Historical Society. The papers of the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist went to the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, while those of the late Chief Justice Warren Burger rest at the College of William and Mary. Some of Rehnquist’s papers are available; Burger’s are not. Justice Lewis Powell’s papers are at Washington and Lee University and are highly accessible through online digitization. Justice Felix Frankfurter split his papers, which are available, between the Library of Congress and Harvard University. (As far as I can tell, Justice Anthony Kennedy has not publicly announced what will happen with his papers, and his chambers did not respond to an inquiry.)

Besides deciding for themselves where to donate their papers, the justices are also free to decide what to donate, which goes more directly to the question of how to solve the mysteries of what happened inside the court. There is a range of possible materials that could be saved in a justice’s files.

These include files on each decided case, which may contain draft opinions as a decision goes through different stages, as well as letters back and forth among the justices asking for changes in drafts, or joining an opinion or advising of plans to dissent or concur separately. Some of these files contain communications between a justice and her law clerks as changes are made, but some justices’ chambers do not save those communications.

Another source of potentially valuable insights is the conference notes of the justices. When the justices meet privately together to discuss and vote on cases, most justices take handwritten notes on what their colleagues said in those discussions. Some researchers consider these files to be the gold standard in historical records, because they place the reader inside the most private court discussions. Others consider these files less reliable because the notes are not verbatim accounts of what was said and reflect the subjective filtering of the note taker.

Either way, these conference notes may be viewed as the most sacrosanct of materials. Justice Hugo Black before his death in 1971 asked his son to burn his conference notes, believing that no one should ever be able to eavesdrop, even years later, on the private discussions of the justices. On a recent trip to the Court of Justice of the European Union in Luxembourg, I learned that records of the deliberations of the justices on that court are supposed to be permanently protected from disclosure.

There are other portions of justices’ files, less relevant to this discussion. Files contain correspondence, speeches, calendars and memos related to governance of the court or the judiciary generally.

What can one learn from a justice’s papers, especially in the “fly on the wall” category?

Justice Stephen Breyer is fond of telling audiences that the story of the Supreme Court is that there is no story, that everything is in the published opinions of the court. It is difficult to reconcile that view, however, with the curiosity and fascination with what happens inside the court when the outcomes are different than what was likely or expected.

Brennan’s papers, to which this writer had access, provide many interesting historical footnotes. They show, for example, how Brennan took over the completion of the case of Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969 after the resignation of Justice Abe Fortas, who had been drafting the decision. The final version is unsigned by the justices, a per curiam decision, meaning “for the court.” The ruling is a pillar of contemporary free speech law, defining the line between unprotected incitement of illegal action and protected strong dissent and passionate advocacy.

Other examples are in the papers of Marshall, who died in 1993 just two years after leaving the court in 1991, and whose papers immediately became public under the terms of his gift to the Library of Congress.

One very specific example involved an appeal over the Justice Department’s controversial approval of a joint operating agreement between the Detroit Free-Press and the Detroit News. In 1989, the Supreme Court upheld the JOA by a 4-4 tie vote. In that situation, the court gives no information to the public; which justices voted on which side, and perhaps why, remain secret. But in Marshall’s papers, newspaper reporters were able to find out that the 4-4 tie occurred because Blackmun changed his mind at the last moment from approving to opposing the JOA. The vote, it was reported from Marshall’s papers, ended up with Rehnquist, O’Connor, Scalia and Kennedy in favor of approving the agreement, and Stevens, Brennan and Marshall, joined by Blackmun, opposing it. The tie had the effect of upholding the lower court’s approval of the JOA.

Relate those small examples to what we wish we knew today. On June 11, the Supreme Court affirmed by a 4-4 tie a ruling of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit in Washington v. United States. Kennedy recused himself, discovering that he had taken part in a much earlier version of the case when he was a judge on the 9th Circuit years ago. The affirmance was a victory for tribal fishing rights, but why, how, and what does it mean for future cases? For now, those questions are unanswerable.

On June 4, the court in an unsigned per curiam decision declined to rule on the merits of a case in which federal courts allowed a pregnant minor in immigration detention to obtain an abortion, over the objections of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Although the issue is likely to arise again, the court essentially vacated the rulings in the minor’s favor and ordered the lower courts to dismiss the case as moot. Why did the court not take on this seemingly important and timely issue or address the government’s claim that lawyers for the minor acted unethically? Those questions, too, are unanswerable for now.

And what of the gerrymandering cases? Long divided over whether partisan gerrymandering raises any constitutional issue that federal courts should decide, the justices raised the expectations of the legal and political communities by agreeing to hear two appeals, Gill v. Whitford from Wisconsin and Benisek v. Lamone from Maryland. But after weeks of anticipation, the justices decided that the challengers in the Wisconsin case did not have sufficient legal injury to challenge the gerrymandering, and then disposed of the Maryland case in an unsigned procedural ruling. Why did the justices decide they were not ready to tackle the constitutionality of political gerrymandering, after so many thousands of words were written in briefs and spoken in arguments? Who blinked?

Legal historians may be able to answer these questions someday, but for now, we wait.

This post has been corrected to reflect that Justice David Souter’s papers will be publicly available 50 years after Souter’s death, not in 2059, 50 years after his retirement.