Empirical SCOTUS: The five frontrunners

With less than one week left until President Donald Trump announces his nominee to fill the second SCOTUS vacancy since he took office, not all names are getting equal attention. Trump indicated the other day that he has narrowed down his initial list to five finalists, including two women. Although all the names on this whittled-down list are not known, a few judges are seen as frontrunners. Almost all lists of potential nominees include Judge Brett Kavanaugh of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, the judge whom Empirical SCOTUS identified in December as a likely nominee in the event of a vacancy. The other judge floating around many pundits’ predictions is Judge Amy Coney Barrett of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit.

Even though the shortlist is not entirely clear, this post analyzes facets of five judges who are likely leading the way. These individuals include Kavanaugh and Barrett, along with Judge Thomas Hardiman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit and Judges Amul Thapar and Raymond Kethledge from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit. Kavanaugh and Kethledge both clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy, as did the most recently confirmed justice — Justice Neil Gorsuch. If either becomes the next justice on the court, this would be the first time that any current or former Supreme Court justice had two former clerks later become justices. Of the remaining judges, Barrett clerked for Justice Antonin Scalia, Hardiman did not clerk and Thapar’s highest-level clerkship was for Judge Nathaniel Jones on the 6th Circuit.

Below is the birth year for each justice who joined the court after 1900, along with the birth years of the five frontrunners.

Judicial experience

These potential nominees bring several unique characteristics to the table. To begin, two of these judges, Thapar and Hardiman, both previously worked at the district-court level (Hardiman in the Western District of Pennsylvania and Thapar in the Eastern District of Kentucky).

A Justices Dataset that includes all Supreme Court justices who joined the court after 1900 (derived from the Supreme Court Justices Database) shows that only four justices – Sonia Sotomayor, Charles Evans Whittaker, John Hessin Clarke and Edward Sanford – also previously worked as judges at the district-court level.

This lack of district-court experience is not the norm for federal judges. A second dataset, the Judges Dataset derived from the Federal Judicial Center’s Biographic Directory of Judges, shows that of all federal judges born after 1850, only 18 percent started out as non-district-court judges. The following figure shows the raw count data of where federal judges who did not first sit on a district court began their careers.

The three judges among the frontrunners who did not first sit on district courts, Kavanaugh, Barrett and Kethledge, all began their judicial careers on federal courts of appeals.

Except for Justice Elena Kagan, all of the current Supreme Court justices previously served on one of the courts of appeals. Not only do justices tend to hail from courts of appeals generally, but they also tend to hail from particular courts of appeals. The next figure looks at the courts of appeals on which justices in the Justices Dataset sat before joining the Supreme Court.

Three of the judges, Kavanaugh, Thapar and Kethledge, served on the top two courts in the figure — the 6th and D.C. Circuits.

Backgrounds

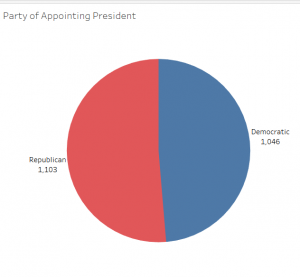

Not surprisingly, all of the frontrunners were nominated to courts of appeals by Republican presidents. Kethledge, Kavanaugh and Hardiman were nominated by George W. Bush, and Thapar and Barrett were nominated by Trump. The majority of judges in the Judges Dataset were initially nominated by Republican presidents as well.

Across time, presidents have had varying opportunities to nominate federal judges. Trump is already a distinct player in this area. The following figure looks by appointing president at counts of judges appointed to their first federal judgeship based on data in the Judges Dataset.

Two Democrats and two Republicans — Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan — lead the pack with the most appointments. With 37 nominations for judges’ first federal judgeships, Trump has gained ground on those presidents in his first two years in office.

Geography is also an important background element for federal judges, because judges tend to come from specific geographic locales. The figure below shows the relative number of federal judges in the Judges Dataset who were born in the various states.

The top four states where most judges in this set were born are New York, Pennsylvania, California and Illinois. Of the frontrunners, Kavanaugh was born in Maryland, where between one and two percent of federal judges in the dataset were born; Kethledge was born in New Jersey, along with between 3 and 4 percent of the set; Thapar was born in Michigan, along with just under 3 percent of the dataset; Hardiman was born in Massachusetts, where close to 3 percent of the judges in the set were born; and Barrett was born in Louisiana, along with just under 3 percent of the Judges Dataset.

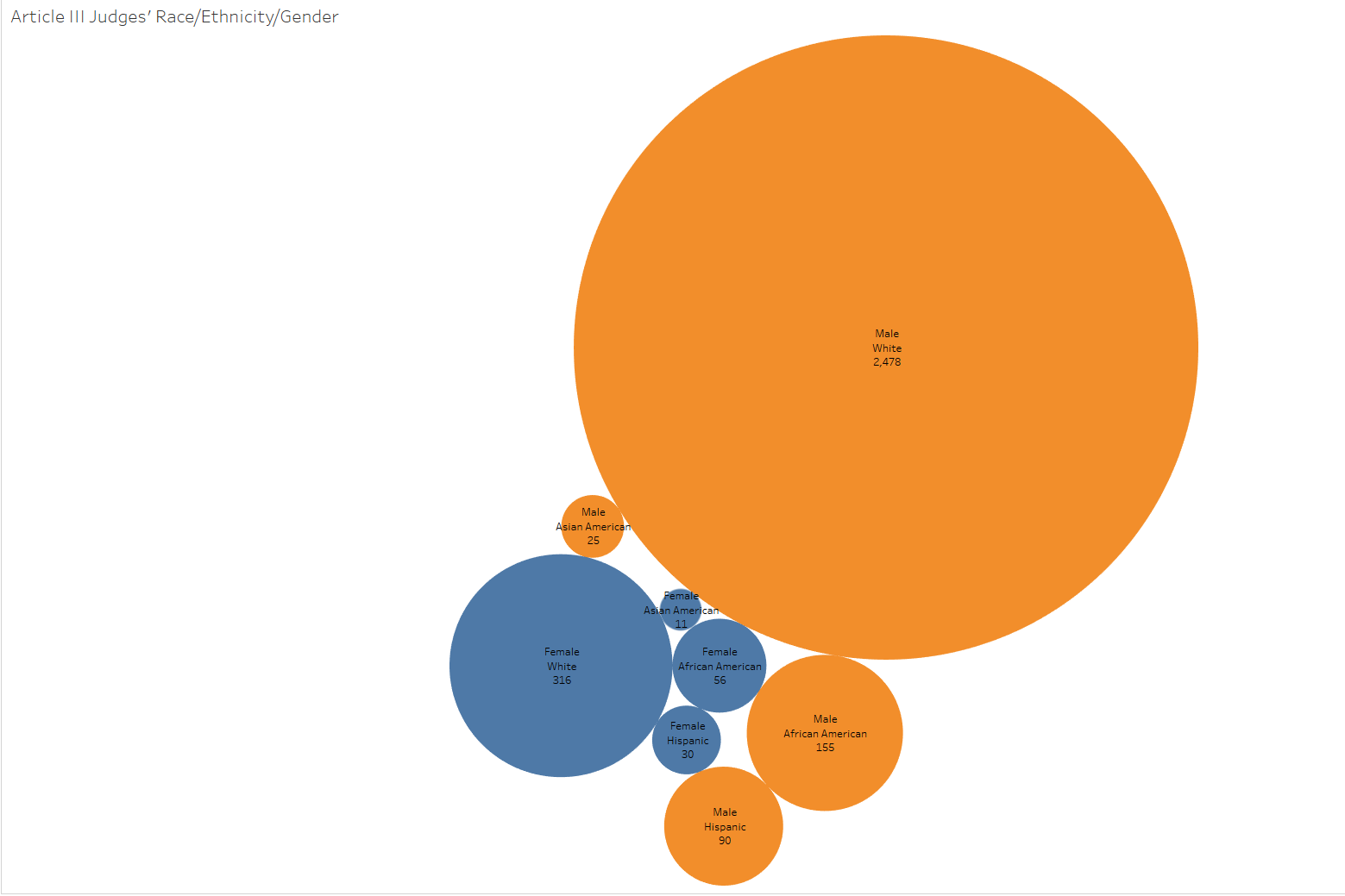

The majority of frontrunners fit the most common racial/gender demographic profile of federal judges in the Judges Dataset — white and male.

Qualifications

The frontrunners are all recognized as top conservative minds on the federal judiciary. Each comes from a distinguished academic background, including a highly ranked law school, although none of them went to the most common law school of justices in the Justices Dataset — Harvard Law School.

Kavanaugh went to the school that produced the second most judges in the set (Yale Law), Kethledge went to the fourth school on the list (Michigan Law), and Thapar went to Chief Justice Earl Warren’s alma mater (UC Berkeley Law). Barrett and Hardiman went to Notre Dame and Georgetown Law respectively, either of which would be a first for a Supreme Court justice.

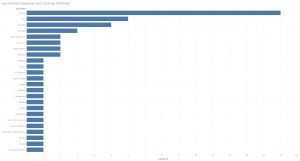

All federal judges are rated by the American Bar Association based on their qualifications. The neutrality of this process has been under scrutiny over the past several years. Nonetheless, this is one of the measures of nominees reviewed by the senators prior to confirmation votes. Judges in the Judges Dataset received one of five ratings from the A.B.A. — exceptionally well-qualified, well-qualified, qualified, not qualified or not qualified by reason of age. The last figure shows this breakdown for the Judges Dataset.

Of the frontrunners, Thapar and Hardiman both earned well-qualified ratings, while Kethledge and Barrett were voted well-qualified by a substantial majority and qualified by a minority of A.B.A. raters. Kavanaugh had the unusual experience of having his qualifications rating lowered from a majority well-qualified and minority qualified to a majority qualified and minority well-qualified. Several Republican members of Congress criticized this alteration as motivated by partisanship.

A few final notes

For the justices in the Justices Dataset the average time between nomination and a final vote in the Senate was 32 days, although that average time becomes greater if we curtail the sample to more recent nominations. The average hearing length for these justices was three days, although the maximum was 19 for Justice Louis Brandeis, and 14 of the justices had single-day hearings.

The context provided above is not intended to answer the question of which judge Trump will choose as the nominee. The comparisons are useful, though, in understanding ways we can distinguish among the candidates.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.