Opinion analysis: Florida wins another chance, and the case goes back to the drawing board

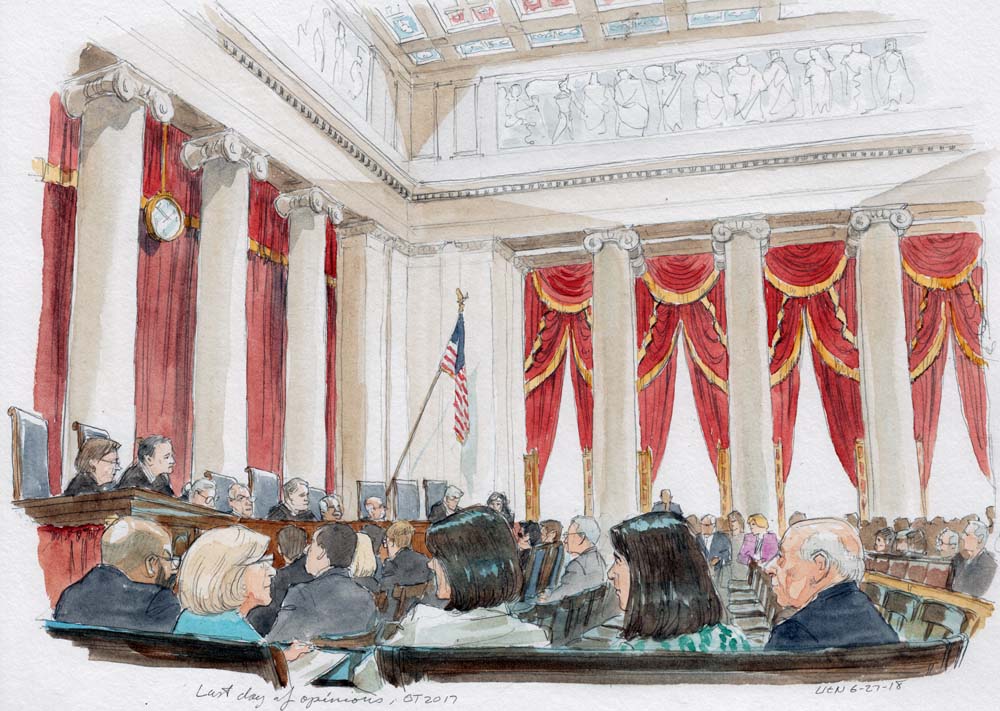

on Jun 27, 2018 at 5:27 pm

On the last possible decision day, the Supreme Court issued a 5-4 decision in Florida v. Georgia written by Justice Stephen Breyer and joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg and Sotomayor. Justice Thomas filed a dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Alito, Kagan and Gorsuch.

In a win for Florida, which is seeking an equitable allocation of the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River system under the court’s original jurisdiction, the court held that the special master assigned to hear the case had applied too high a standard of review for redressability. The court held that although a state has to show via “clear and convincing evidence” that it has suffered an “invasion of rights” and “substantial injury” when seeking equitable apportionment of water between states, this standard does not apply in “respect to a showing of a ‘remedy’ or ‘redressability.’”

The court remanded the case to the special master for further consideration of a variety of evidentiary issues, while reserving judgment on the ultimate disposition of the case.

Brief background:

After more than 30 years of litigation and efforts to resolve allocation of the ACF system, Florida sued Georgia seeking equitable allocation in 2013. The court assigned the case to a special master. Following extensive discovery and a multi-week trial, the special master issued a report in February 2017 rejecting Florida’s argument that Georgia’s water consumption should be limited. He concluded that Florida had “not proven by clear and convincing evidence” that putting a cap on how much water Georgia could consume would actually improve the river flows “at a time that would provide a material benefit to Florida.” Further, he found that because the U.S. Corps of Engineers was not a party to the case, Florida could not actually receive the relief it requested. Florida filed exceptions to the special master’s report, and after another round of briefing, the Supreme Court heard oral argument on January 8, 2018.

Overview of findings:

The court first reviewed the doctrine of equitable apportionment, finding that both Georgia and Florida possess “an equal right to make reasonable use of the waters of the stream.” Second, the court’s “effort is to secure an equitable apportionment without quibbling over formulas.” Third, a state complaining of an injury “must prove by clear and convincing evidence some real and substantial injury or damage.” In addition, the complaining state bears the “initial burden” of showing that the injury can be redressed, and that an equitable apportionment can result in some benefit: “An effort to shape a decree cannot be a ‘vain thing.’” Fourth, when a state has met its initial burden of showing “real or substantial injury,” the court will seek to “arrive at a just and equitable apportionment” using a flexible and not formulaic approach that takes into consideration all relevant factors. The court then cited several equitable-apportionment cases that had been remanded for additional factual findings.

After comparing these precedents with the standard applied by the special master, the court concluded “that the Special Master applied too strict a standard when he determined that the Court would not be able to fashion an appropriate equitable decree.” The court further stated that “[i]n our view, unless and until the Special Master makes the findings of fact necessary to determine the nature and scope of likely harm caused by the absence of water and the amount of additional water necessary to ameliorate that harm significantly, the complaining State should not have to prove with specificity the details of an eventually workable decree by ‘clear and convincing’ evidence. Rather, the complaining State should have to show that, applying the principles of ‘flexibility’ and ‘approximation’ we discussed above, it is likely to prove possible to fashion such a decree.”

The court independently reviewed the record before the special master and concluded that “at this stage, Florida met its initial burden in respect to remedy but noted that a remand is necessary “to conduct the equitable-balancing inquiry.”

The court raised five critical questions, quoted below:

- First, has Florida suffered harm as a result of decreased water flow into the Apalachicola River?

- Second, has Florida shown that Georgia, contrary to equitable principles, has taken too much water from the Flint River?

- Third, if so, has Georgia’s inequitable use of basin waters injured Florida?

- Fourth, if so, would an equity-based cap on Georgia’s use of the Flint River lead to a significant increase in streamflow from the Flint River into Florida’s Apalachicola River?

- Fifth, if so, would the amount of extra water that reaches the Apalachicola River significantly redress the economic and ecological harm that Florida has suffered?

After reviewing the evidence for the first through third questions, to which the Special Master assumed the answer was yes, the court focused on the fourth and fifth questions.

For the fourth question, the court found that putting a consumption cap on Georgia would lead to benefits: “[T]he record suggests that an increase in streamflow of 1,500 to 2,000 cubic feet/second is reasonably likely to benefit Florida significantly.” The court then examined whether such water would be delivered through the ACF system by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers under its revised “Master Manual” in various types of conditions, including normal or “non-drought” operations” and “drought operations.” After significant analysis, the court eventually concluded “even when the Corps conducts its operations in accordance with the Master Manual, Florida’s proposed consumption cap would likely mean more water in the Apalachicola [River system].”

Although the majority rebutted the views of the dissent about whether the consumption cap would allow more water to reach Florida, the majority eventually concluded that “without explicit findings, it is neither possible nor prudent for us in the first instance to read through this voluminous record and discover who is right on this matter of how much extra water there will be, when, and how much Florida would benefit from the extra water that there might be. That is why we are sending this case back for more findings.”

The court then examined the fifth question in detail: Would the amount of water that reaches the Apalachicola significantly redress the economic and ecological harm suffered by Florida? The court found evidence that the answer to this is yes, but noted that the special master’s report did not explicitly answer the question and therefore sent this question back on remand.

After summarizing its conclusions on the evidentiary issues, the court then addressed the U.S. Army Corps’ of Engineers’ role, noting the U.S. had agreed to abide by any decision of the court. While recognizing that “the Corps must take account of a variety of circumstances and statutory obligations when it allocates water,” the court concluded that “in this case, the record leads us to believe that, if necessary and with the help of the United States, the Special Master, and the parties, we should be able to fashion [a decree]” that offers “meaningful relief.”

Finally, the court reiterated that “Florida will be entitled to a decree only if it shown that the benefits of the apportionment substantially outweigh the harm that might result.” It then listed a set of questions for the special master to assess, along with others that may also arise, while noting that answers “need to not be mathematically precise or based on definite present and future conditions.”

Dissent:

In a 39-page dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas focused on the extensive review by the special master and would have upheld his findings. In reaching this conclusion, the dissent first reviewed factual information about Florida’s and Georgia’s “respective interests.” The dissent also reviewed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “extensive operations.”

Turning to the law, the dissent examined the court’s equitable-apportionment jurisprudence “or at least what used to be the rules before the Court’s opinion muddled them beyond recognition.” It focused on the “balance of harms analysis” and whether the “appreciable-benefit requirement” had been met, finding that “Florida could not prove that it would receive more water when it needed it” if a consumption cap were placed on Georgia. The dissent disagreed vehemently that Florida’s ability to prove an appreciable benefit required further hearing, noting that the Special Master had already conducted a full trial. The dissent also disagreed with the majority’s findings on how future uncertainties might affect the ability to fashion a decree under previous case law, as well as the lack of Article III standing. According to the dissent, the “Court’s suggested order of operations [for the Special Master to review on remand]… would fundamentally transform our equitable-apportionment jurisprudence,” and a “do-over” would subvert the Supreme Court’s independent review. Finally, the dissent focused on the Corps of Engineers’ role, finding that “the Corps will not change its existing practices, even if this Court caps Georgia’s water use.” In conclusion, Thomas noted that “[i]f we contrast the de minimus benefits that Florida might receive from small amounts of additional water during nondroughts with the massive harms that Georgia would suffer if this Court cut its water use in half during droughts, it is clear who should prevail in this case.”

Next steps:

This case has now been remanded to the special master for further proceedings. While the case has been pending, other litigation challenging the Corps’ revised Master Manual for the ACF system has been filed. Both the court in this decision and the special master in previous communications have encouraged the states to negotiate an outcome. Whether this happens remains to be seen; in the meantime, stay tuned for an updated schedule from the special master.