Ask the author: The people surrender nothing

on Apr 26, 2018 at 2:52 pm

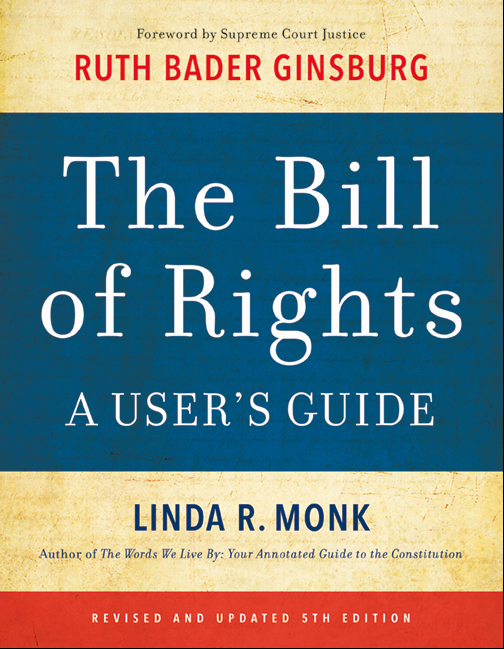

The following is a series of questions prompted by the publication of Linda R. Monk’s “The Bill of Rights: A User’s Guide” (Hachette Book Group, 2018, 5th Ed.). In 1788, Alexander Hamilton argued in “Federalist 84” that a Bill of Rights was unnecessary in a democracy because “the people surrender nothing; and as they retain everything, they have no need of particular reservations.” Not everyone was so convinced, and – in what Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in her foreword, calls “one of the great compromises that helped assure passage of our founding document” – the states in 1791 ratified a “terse” Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution.

This book – the fourth in a series of updates from the original version, which was written for the 1991 bicentennial of the Bill of Rights and which won the American Bar Association’s Silver Gavel Award for public education about the law – presents the history of these rights and their interpretations by the Supreme Court.

Monk’s other books are “The Words We Live By: Your Annotated Guide to the Constitution” and “Ordinary Americans: U.S. History Through the Eyes of Everyday People.”

* * *

Welcome, Linda, and thank you for taking the time to participate in this question-and-answer exchange for our readers.

Question: In her foreword, Justice Ginsburg writes that “the judiciary does not stand alone in guarding against governmental interference with fundamental rights,” which “is a charge we share with the Congress, the president, the states, and with the people themselves.”

I note that your subtitle is “A User’s Guide.” How are you hoping readers might use this book?

Monk: My goal was to make the principles I learned at Harvard Law School accessible to everyday citizens. But I’m pleased that many lawyers enjoy the book as well. As James Madison said, “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” So knowledge comes first, but then comes practice. The stories of the citizens who stood up for constitutional principles — Fannie Lou Hamer, Mary Beth Tinker, Susette Kelo, Simon Tam — inspire me and I hope will inspire other citizens as well.

Question: You write that the Bill of Rights is “a living document” that “did not come with an instruction manual.” Can you elaborate on this idea?

Monk: I’m talking about the effect of the Bill of Rights on citizens, not on judges. As you know, the idea of a “living” Constitution is anathema to certain schools of jurisprudence, notably that of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. They believe this concept gives judges a blank check. But I quote Justice William O. Douglas who wrote in 1961, “[T]he reality of freedom in our daily lives is shown by the attitudes and policies of people toward each other in the very block or township where we live.” That’s the idea I want to emphasize, that our rights are enforced by our mutual respect as citizens.

Question: The first 10 amendments to the Constitution compose the Bill of Rights, and you devote a chapter to each amendment. You add one more chapter for the 14th Amendment.

What’s the relationship between this amendment and the Bill of Rights?

Monk: The 14th Amendment, which turns 150 years old this July, is really a second Bill of Rights, because it nationalizes the freedoms that previously only restricted the federal government. The Supreme Court used the 14th Amendment to apply the Bill of Rights bit by bit to state and local governments, which affect the most people. Before this process of “incorporation,” the Bill of Rights did not impact most Americans and few civil-liberties cases made it to the Supreme Court. In addition, the 14th Amendment for the first time introduced the principle of equality to the Constitution. “Equal protection of the laws” meant that government had to give legal justification when it treated citizens differently. And perhaps most important, the 14th Amendment defined citizenship for both the state and national governments, a process that previously had been left to the states.

Question: A lot has happened at the Supreme Court since the most recent version of this book came out in 2004. I note what must be new discussions of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (First Amendment, campaign finance), District of Columbia v. Heller (Second Amendment, individual right to bear arms), Glossip v. Gross (Eighth Amendment, methods of execution), and Obergefell v. Hodges (14th Amendment, same-sex marriage), among others.

Which amendment would you say has seen the most development and attention from the Supreme Court over the past 14 years? In what direction has the law developed?

Monk: During the past 14 years, there have been substantial developments in multiple areas, as you cite. Certainly, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment to fully adopt an individual right to bear arms is significant, although several prominent liberal scholars also embraced that approach. The real frontier is how this right can reasonably be limited, just as every other right in the Bill of Rights has limits. But I think the struggle of LGBTQ Americans for protection under the 14th Amendment is the most momentous change. However, neither LGBTQ persons nor women enjoy the “suspect class” status that requires “strict scrutiny” as in racial discrimination.

Question: Your chapter on the First Amendment is at least twice the size of your chapters on every other amendment. What makes this amendment so important?

Monk: I’d say it is the amendment Americans cherish most, although they might not be able to list all five freedoms it encompasses. It protects freedom of expression — including religion, speech, press, assembly and petition. There is a lot of history and a lot of litigation about those rights, and of course a lot of reader interest.

Question: In February, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his dissent from the court’s denial of certiorari in Silvester v. Becerra that “the Second Amendment is a disfavored right.”

What do you think he means by this, and could you put his words into a larger context for our readers?

Monk: Far be it from me to put words in Justice Thomas’ mouth. But I gather from reading his dissent that he believes multiple lower courts, and the Supreme Court, are not treating limits on the Second Amendment as stringently as they would limits on, for example, First Amendment rights. Yet in the past century of litigation, the court has upheld time, place and manner restrictions; excluded libel, slander, active threats and pornography from free speech protection; and limited the scope of First Amendment rights in schools and prisons. The Second Amendment may just be catching up.

Question: You note that the Third Amendment “has never been the subject of a Supreme Court decision.” Can you remind us court-watchers what this amendment’s all about?

Monk: The Third Amendment prohibits the quartering of troops in homes during peacetime, and in wartime without lawful procedures. Although it is viewed as a relic of the Revolutionary War, the Third Amendment has been cited as support for an unenumerated right of privacy — along with the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth and 14th Amendments.

Question: You write that the Fifth Amendment is a “constitutional hodgepodge,” the “longest and most diverse amendment in the Bill of Rights.” Can you elaborate?

Monk: It’s the longest by sheer word count, and it embraces a broad range of rights under both civil and criminal law. Of course, the best known is the “right to remain silent” popularized on television. This right stems from the Star Chamber in England, which forced witnesses to swear to tell the truth (under an oath to God, with the ultimate penalty of eternal damnation) and then asked a wide range of questions about a variety of subjects. Eventually, someone would be found guilty of something, one way or the other. The Fifth Amendment also protects “due process of law,” perhaps the most fundamental type of justice under civil and criminal law. In addition, it ranges from the grand jury in criminal law to just compensation when private property is taken by the state. A very wide scope of rights.

Question: Why do you write that the Ninth Amendment “is one of the most controversial provisions in the Bill of Rights”?

Monk: My con-law professor John Hart Ely wrote that believing in the Ninth Amendment was like believing in ghosts (He was a utilitarian and not a fan of natural-rights theory.). Judge Robert Bork compared it to an ink blot. Randy Barnett of Georgetown Law sees it as a source of unenumerated rights, just as Article I’s necessary-and-proper clause is a source of unenumerated powers. Many Americans are concerned about unelected judges being given a blank check to create rights; for others, the Ninth Amendment is that blank check. For whatever reason, the courts have been more willing to protect unenumerated rights such as privacy and travel and marriage under the 14th Amendment, even though, as Justice Arthur Goldberg said, the Ninth may be more on point.

Question: The Supreme Court has yet to decide a number of cases this term involving the Bill of Rights, including Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (First Amendment, public-accommodations laws), Carpenter v. United States (Fourth Amendment, electronic privacy), and City of Hays, Kansas v. Vogt (Fifth Amendment, compelled statements).

What do you see as the biggest potential shifts in doctrine this year and into the near future?

Monk: I’m a better explicator than prognosticator, at least on the legal reasoning that should be part of any Supreme Court opinion. That’s what I focus on in my book: what the court said rather than what it might do. While I supported the outcome in Obergefell, on equal-protection grounds, I don’t understand the rationale for a liberty interest of persons “to define and express their identity.” I foresee that phrase engendering litigation. In Masterpiece, I have a personal interest because my mother made and decorated wedding cakes. And while I valued her creativity, I saw it as comparable to that of any artisan who provides a service — whether it is cake, furniture or fried chicken. And to me, fried chicken is definitely an art form.

Question: You write that for the constitutions of foreign nations, the “U.S. Bill of Rights serves as a reference point, if not always as a model.”

This question could be the subject of a whole book, but which amendments stand out as models and which as only “reference points,” and why?

Monk: The U.S. Bill of Rights applies to so-called “negative” rights rather than “positive” rights. So Americans are to be free from government restrictions on certain rights, but the Bill of Rights does not say the government must ensure positive rights — such as the right to health, education and a job. In other countries, such as South Africa, these positive rights are more prominent in their constitutions. But without a stable form of government can such rights truly be protected? The most important idea I learned in law school is “there is no right without a remedy.” That’s what makes the U.S. system unique: Our rights have legal remedies through the Constitution, which cannot be changed by majority rule.