Argument analysis: No clear winner in VA contracting case

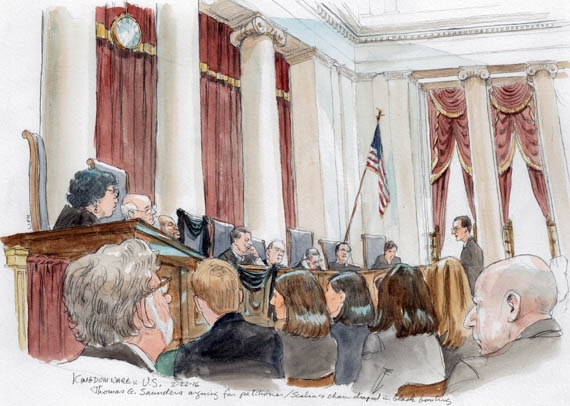

After a warm and lengthy tribute by Chief Justice John Roberts to the late Justice Antonin Scalia, the Court got back to work this morning hearing oral arguments. First up was Kingdomware Technologies v. United States, a dispute over the scope of a 2006 law aimed to benefit veterans. After fifty-eight minutes of oral argument, there was no clear winner in the case. If anything, the Justices seemed to be trying to decide which side’s rule was more palatable – or, perhaps, less unpalatable.

Kingdomware is a Maryland-based company owned by a veteran who became permanently disabled as a result of injuries sustained during his service. It argues that the law requires the Veterans Administration to award contracts to a veteran-owned small business based on the “Rule of Two” – that is, whenever there is a “reasonable expectation” that at least two veteran-owned small businesses will submit offers to fill the contracts and that the contract can be awarded to one of them at “a fair and reasonable price that offers best value to the” United States.

Many of the Justices’ concerns about Kingdomware’s proposed rule stemmed from the federal government’s repeated contention that requiring the Veterans Administration to use the Rule of Two whenever it wants to buy anything would bog down the agency’s procurement system. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, for example, expressed concern about what might happen when the VA has an urgent need for supplies or services. Attorney Thomas Saunders, representing Kingdomware, tried to reassure the Court that the Rule of Two only comes into play “when you have both fair and reasonable price and best value to the United States.” “So if there’s truly an urgent need,” he continued, “and it’s not going to be met by going through the Rule of Two, then” there might be “leeway” for the VA to bypass the Rule of Two by finding that both criteria were not met. That did not mollify Chief Justice John Roberts, who suggested that the latitude that Kingdomware was proposing for VA officials could lead to “an awful lot of litigation.”

The Justices also had questions about how they could determine whether Kingdomware’s proposed rule is in fact “unworkable,” as Justice Anthony Kennedy put it. Ginsburg chimed in, suggesting that there was “no empirical evidence” to support Kingdomware because the set-aside at issue in this case was new. “We don’t have any experience at all,” Ginsburg told Saunders.

Justice Stephen Breyer pressed Saunders as well. If the law means what Kingdomware says it does, he told Saunders, then all VA contracts would go to veterans. “It’s very surprising to me,” he continued, that “Congress would have wanted the Veterans Administration to buy everything from veterans.” Saunders countered that the number of veteran-owned businesses was actually relatively small, but that prompted Roberts to remark that, if Kingdomware prevails, a lot more veterans will start their own businesses.

Assistant to the Solicitor General Zachary Tripp, representing the United States, quickly ran into tough questions as well. Ginsburg interrupted him after just one sentence, asking him to “explain why the government walked away from what was a winning position in the” lower court: that the law requires the VA to use the Rule of Two when it wants to use a particular procurement to meet its annual goals for awarding contracts to veteran-owned small businesses, but also allows it to use the Federal Supply Schedule (a program in which the government negotiates a deal for products and services up front, so that agencies can place orders without having to solicit bids on the open market) as long as it meets those goals. “I mean, it’s really odd,” she said. And later on, she complained that the government was “putting us in the position of being a court of first view in a rather dense area. This court,” she noted pointedly, doesn’t really do that. Justice Samuel Alito took a somewhat cynical view, asking Tripp whether the “real answer to this question” is “that the VA regulations don’t say anything about goals.”

For her part, Justice Elena Kagan seemed skeptical of the government’s interpretation. Regardless of its policy implications, she told Tripp, once the federal government concedes (as it did) that an order from the Federal Supply Schedule is a contract, “the statute just seems pretty clear.” Sotomayor and Kennedy focused on practical concerns, wondering aloud why the VA couldn’t buy items from veteran-owned vendors on the FSS. Tripp acknowledged that “the upfront cost” of doing so is “not that big,” but he suggested that such a practice might also create a “litigation risk” from vendors who were not chosen.

Although the mood in the Courtroom was relatively somber, there were moments of levity. One came when Tripp, in response to a question about whether the goals for government contracts to veteran-owned businesses are merely aspirational. Tripp told the Justices that the goals have “a huge impact” on the government’s contracting practices. “In most years,” he asserted, “we’re crushing those goals.” That statement led the Chief Justice to ask quizzically, does “that mean you’re meeting them?” It did.

The Justices spent only a few minutes on the question whether the case is moot because the contract at the center of the dispute has already been performed – an issue that had prompted the Justices to remove the case from the November argument calendar and order additional briefing. Justice Samuel Alito asked Saunders to clarify exactly what relief Kingdomware could receive if it were to prevail, while Justice Sonia Sotomayor observed that at an earlier stage in the case Kingdomware had “stipulated away” its right to recover costs from the government – telling Saunders that his client did have a right to relief, “but you gave it away.” But in the end, the Justices seemed satisfied with Saunders’s argument that a declaratory judgment for Kingdomware would establish the legal meaning of the statute, with which the VA would have to comply “going forward.”

Even if there was no clear winner, that doesn’t necessarily mean it will be a close case. Given the somewhat esoteric nature of the issues involved, this seems like the kind of case in which, in the end, most or all of the eight Justices could coalesce around a single interpretation of the law. It’s just hard to say which reading will win in the end.

Posted in Analysis, Merits Cases

Cases: Kingdomware Technologies Inc. v. United States