Argument analysis: Second time around no easier for Justices in standing case

on Nov 2, 2015 at 4:23 pm

Nearly four years ago, the Court heard oral arguments in a case involving the constitutionality of a provision of the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act that allows homeowners to sue banks and title companies that pay kickbacks for the closing of a mortgage loan, even if the homeowners were not hurt because the kickbacks do not affect the prices that the homeowners pay for the loans or the quality of the services that they receive. The Justices would dismiss that case, First American Financial v. Edwards, seven months later, without either a ruling on the merits or any explanation for the dismissal. In Spokeo, Inc. v. Robins, the case of a Virginia man who alleges that the Internet “people search engine” published inaccurate information about him, the Justices had before them a similar question as in First American: does the mere fact that Spokeo violated the Fair Credit Reporting Act, without more, give Thomas Robins a legal right – known as “standing” – to sue? Today’s oral arguments in the case gave a glimpse into how the Justices may have been stymied by First American, and how they are likely to be closely divided on whatever decision they eventually reach.

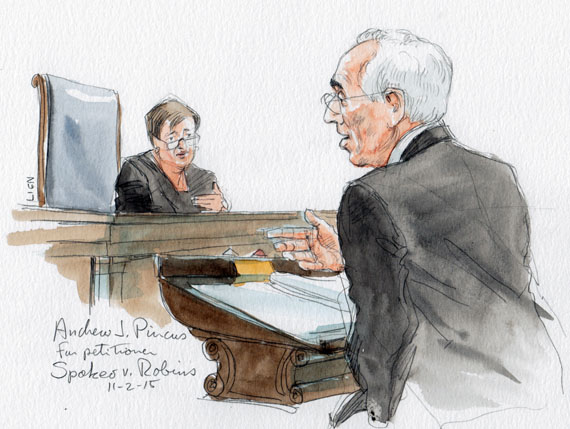

Let’s start with what doesn’t seem likely: a ruling that plaintiffs like Robins only have to allege a violation of a right created by a statute, without any need to show a concrete, “real world” harm from the violation. Of the nine Justices, only two – Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg — seemed open to this possibility. Sotomayor told attorney Andrew Pincus, arguing on Spokeo’s behalf, that the Court had “always said that an ‘injury in fact’ is the breach of a legal right.” Ginsburg echoed that sentiment a few minutes later, suggesting that it would be “very strange” to have a rule in which “if we have some historic practice where damages are awarded to someone who has no out-of-pocket loss, if the common law says so, it’s okay, but if Congress says so, it’s not.”

On the other hand, some of the Court’s more conservative Justices seemed ready to agree with Spokeo that Robins and others like him need to be able to point to actual harm from a violation of a statute, rather than just the violation of the statute itself. Justice Antonin Scalia, for example, posited that, under Robins’s interpretation, the failure of a credit reporting agency to provide a “1-800” number (required by the FCRA) would allow anyone to sue, even if it didn’t affect them at all. You need more than just a violation of what Congress has said is a legal right, Scalia emphasized. Chief Justice John Roberts felt the same way. During an exchange with William Consovoy, who argued on behalf of Robins, he described a hypothetical statute that allows damages of $10,000 for the publication of false information about you. Would someone whose unlisted phone number is published but is published incorrectly, Roberts asked dubiously, have a legal right to sue?

But several Justices focused on a third, narrower option: the idea that Robins was actually injured when Spokeo published false information about him. This would allow Robins’s lawsuit to go forward, without forcing the Court to choose between opening the federal courts to frivolous but possibly massive class-action lawsuits (Spokeo’s prediction if Robins were to prevail) and closing the courthouse doors to potentially important privacy, civil rights, environmental, and patent lawsuits (Robins’s prediction if Spokeo were to prevail). Justice Elena Kagan, who was among the most active questioners today, led the charge on this point, asking Pincus why, even if she agreed that “you need a concrete injury,” “wouldn’t the dissemination of false information in a credit report be a concrete injury?” She continued: It “seems like a concrete injury to me. If someone did it to me, I would feel harmed.” Justice Stephen Breyer agreed, adding that there can be economic harm, but also psychic harm, from the publication of incorrect information. And Sotomayor seemed to concur as well, telling Pincus that she knows “plenty of people of single people who” check online to see whether a potential date is married. Justice Samuel Alito was more skeptical, though, asking Consovoy whether there was any evidence that anyone other than Robins himself conducted a search for his information. If not, Alito posited, any harm is purely speculative.

As is so often the case, it looks like the Court’s decision may hinge on Justice Anthony Kennedy. And Kennedy was hard to read today. Although at one point he suggested to Pincus that a company like Spokeo, as a credit reporting agency, might be held to a higher standard than false information on the Internet more broadly, he also emphasized to Consovoy that one of the Court’s earlier cases required a de facto, or actual, injury.

But even if five Justices were to agree that Robins had suffered a “real world” injury (and that’s a big “if”), it’s still not clear where the Court would go from there, given that the question technically before the Court is whether Congress can authorize lawsuits based on the violation of a statute when the plaintiff has not actually been harmed. So when Breyer recounted errors in Robins’s credit report and asked Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart (arguing on behalf of the United States in support of Robins) whether, for purposes of deciding this case, Spokeo’s errors would constitute a sufficiently concrete injury to Robins, the Chief Justice quickly countered that “that’s not what the” court of appeals said. That court, Roberts emphasized, ruled only that Robins had standing because his legal rights under the FCRA had been violated. Kagan offered another characterization of the Ninth Circuit’s decision; while she conceded that it was “not a good opinion,” she nonetheless maintained that the Ninth Circuit acknowledged that that the harm to Robins was sufficiently concrete. Pincus pushed back against that characterization during his rebuttal, emphasizing that the Ninth Circuit relied only on the statutory violation to determine that Robins had standing. That prompted Sotomayor to ask Pincus, somewhat tartly, “Are we ruling on the outcome or the reasoning?”

In the end, that may be the big question. At the moment, the case is too close to call.