A few notes on unanimity

on Jul 10, 2014 at 10:40 am

Over the past few weeks, there has been a raft of opinion pieces and commentary addressing the Supreme Court’s startling number of unanimous opinions during October Term 2013. As our Stat Pack shows, there were forty-eight 9-0 or 8-0 decisions during the Term, totaling sixty-six percent of all merits opinions. Neal Katyal noted that this is the highest percentage of unanimous opinions in any single Term since World War II.

But there may be more to the story. Some commentators have termed this year’s unanimity “faux-nanimity” for the seemingly high number of cases in which the Justices voted for the same judgment – thereby satisfying the most fundamental requirement for unanimity – while evincing serious disagreement over the legal reasoning used to reach that conclusion.

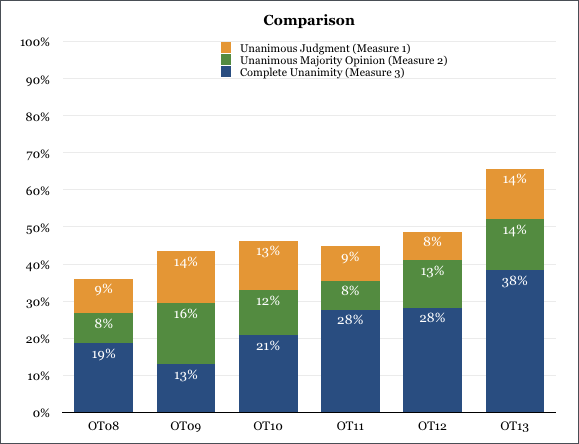

To get a closer look at how OT13 really stacked up to previous years, I created three different measures of unanimity and analyzed the past six Terms. Based on my review of these measures, there seems to be something truly uncommon about the level of unanimity that we saw during OT13. Let’s take a look at each measure.

Measure #1: The first and broadest measure of unanimity is precisely the one that we use in the SCOTUSblog Stat Pack: any case in which all the Justices voted for the same judgment, i.e., to affirm, reverse, or vacate the decision below. By this measure, the Court was unanimous in forty-eight cases during OT13, sixty-six percent of all cases during the Term.

I looked at the level of unanimity reached over the past six years according to this measure:

There has been a general increase in the level of unanimity over the past six years. The Justices reached a unanimous judgment in just thirty-six percent of cases during OT08 (the lowest rate during these six years) and peaked at a startling sixty-six percent during OT13.

This measure captures several important cases from OT13 in which the Justices agreed on the same judgment but for very different reasons. The poster cases for this phenomenon are the recess appointments case, NLRB v. Noel Canning, and the abortion clinic buffer zone case, McCullen v. Coakley. In Noel Canning, for example, five Justices held that the recess appointments in question were invalid because they were made during a three-day break rather than during a longer one, but Justice Scalia wrote separately (in an opinion that was joined by three other Justices) to express his view that the appointments were invalid for different, broader reasons.

The phenomenon of fractured 9-0 decisions obviously predates OT13 and includes several high-profile cases from recent years such as Morrison v. National Australia Bank (OT09), United States v. Jones (OT11), and Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum (OT12).

Measure #2: The second measure counts only those cases in which every Justice joined some part of the majority opinion. This approach takes a more forgiving view of unanimity and allows individual Justices to write concurring opinions that expand on their view of a case. However, this measure still does not count cases in which five Justices join together for a majority opinion but the other four Justices agree with the result but not the reasoning. For example, this measure does not count McCullen as a unanimous decision because only four Justices joined the majority opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts; Justice Scalia concurred in the result only, with a separate opinion that was joined by Justices Thomas and Kennedy, while Justice Alito filed a separate opinion in which he also concurred in the result only.

By this measure, the Court was unanimous in thirty-eight cases during OT13, fifty-two percent of all cases during the Term.

By this measure there has been a consistent uptick in unanimous decisions since OT08, with the Court nearly doubling its percentage of unanimous opinions over six Terms. During OT13, the Justices saw a significant increase in the number of unanimous opinions to cross the fifty-percent threshold for the first time in recent years.

A key case in this category from OT13 is Lane v. Franks, in which the Court held that testimony in a criminal prosecution by a government employee was protected by the First Amendment. In that case, Justice Sotomayor wrote a majority opinion that was joined by the full Court, but Justice Thomas filed a concurring opinion (joined by Justices Scalia and Alito) to emphasize that, in his view, the majority opinion left for another day certain larger constitutional questions that were not directly implicated by the case.

Looking back past OT13, noteworthy recent cases that fall into this category include Wal-Mart v. Dukes (OT10), Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC (OT11), and Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics (OT12).

Measure #3: The third and narrowest measure of unanimity looks at only those cases in which every Justice agreed with every other Justice. In these cases, every Justice joined the majority opinion in full and without reservation. There are no concurring opinions in these cases, and no Justices withheld their vote from any part of the majority opinion. By this measure, the Court was unanimous in twenty-eight cases during OT13, thirty-eight percent of all cases during the Term.

Once again, OT13 stands out for the high degree of unanimity. Although none of the high-profile cases from this Term fall into this category, there are several mid-major cases from the past year that qualify. In Wood v. Moss, the Justices unanimously agreed that two Secret Service agents who moved protesters away from President George W. Bush during a 2004 protest are entitled to qualified immunity from the protesters’ First Amendment suit. In Limelight Networks v. Akamai Technologies and POM Wonderful v. Coca-Cola, the Supreme Court issued unanimous rulings in long-awaited cases on two-party patent infringement and claims under the Lanham Act, respectively. In Susan B. Anthony List v. Driehaus, the Justices unanimously held that a pre-enforcement challenge to Ohio’s “false statements” law was justiciable. However, if the case comes back to the Supreme Court on the merits of that challenge, it is safe to assume that the Justices might not reach the same level of unanimity.

Looking back beyond OT13, there are also a handful of noteworthy cases that were decided by a single unanimous majority opinion. For instance, in Florida v. Harris (OT12), the Justices unanimously held that a positive identification by a drug-sniffing dog was typically sufficient to create probable cause for a search by police officers. The Justices were also unanimous in an important antitrust decision from OT09, American Needle v. NFL, and in a key personal jurisdiction case from OT10, Goodyear v. Brown.

Conclusion: Taken as a whole, we saw a remarkable level of unanimity during OT13. However, those unanimous decisions took several different forms, and not all were created equally. Ten cases had unanimous judgments but non-unanimous majority opinions, while another ten cases had majority opinions that were either entirely unanimous or unanimous in part but also featured separate concurring opinions. Twenty-eight cases, a recent high, were completely unanimous.

As the yellow and green sections in the chart above demonstrate, the number of cases with fractured coalitions remained about the same as it has during the past five years. The number of truly unanimous cases, shown in blue, however, increased dramatically.

I will leave it to others to hypothesize about why the Court saw a spike in unanimity during OT13. It is equally possible that the Justices coincidentally took on unusually simple cases during OT13, that the Chief Justice has steered the Justices toward narrow, consensus views, or that they forged only fleeting coalitions that will fall apart when more difficult cases arise. A close inspection of the cases supports several different theories surrounding the unusually high unanimity figures for OT13, so Court watchers will be sure to continue monitoring unanimity figures over the coming years.