Cert.-stage amicus “all stars”: Where are they now?

Five years ago, for this blog and in a follow-up article for Slate, I surveyed more than three years’ worth of cert.-stage amicus activity at the Supreme Court. I declared the U.S. Chamber of Commerce the “cert.-stage champion,” and I observed that “[t]he private groups and advocacy organizations that most frequently urge the court to take a case are overwhelmingly pro-business, anti-regulatory, and ideologically conservative.”

Fast forward five years, and I’ve run the numbers again. Among my findings: the Chamber has cemented its status as the country’s preeminent petition-pusher, and the rightward tilt of the most frequent filers has grown even more pronounced.

Here’s my method: I reviewed every cert.-stage amicus brief filed between May 19, 2009, and August 15, 2012. That time frame is the same (arbitrary) time frame I used the first time but shifted forward five years, allowing for easy comparison. Counting the number of briefs filed by each amicus is straightforward. I counted a brief on behalf of multiple amici as a brief for each one, and I excluded certain amici to focus on private organizations. (The excluded parties include the United States, foreign governments, states, cities, public officials, professors, and other individuals.) Then I ranked the parties by the number of briefs they had filed and researched the outcomes of the top sixteen amici‘s efforts. I computed an amicus‘s success rate as a percentage of the petitions it had supported that were either granted or denied. (That calculation counts a summary disposition as a grant but does not factor in GVRs or the rare amicus brief opposing cert.)

What did I find? First, some overall trends. In just five years, cert.-stage amicus activity has heated up substantially. The total number of amicus briefs swelled by thirty-five percent, and the number of organizations filing them ballooned even more, by about sixty-five percent. Of the nearly 1750 organizations in my most recent study, 348 filed two or more briefs, and 160 filed three or more. Five years ago, those numbers were 259 and 118, respectively. The cutoff to earn a place among the top sixteen amicus filers jumped from eight briefs to ten. The new Sweet Sixteen collectively filed eighty more briefs than their counterparts five years ago. In short: more, more, more.

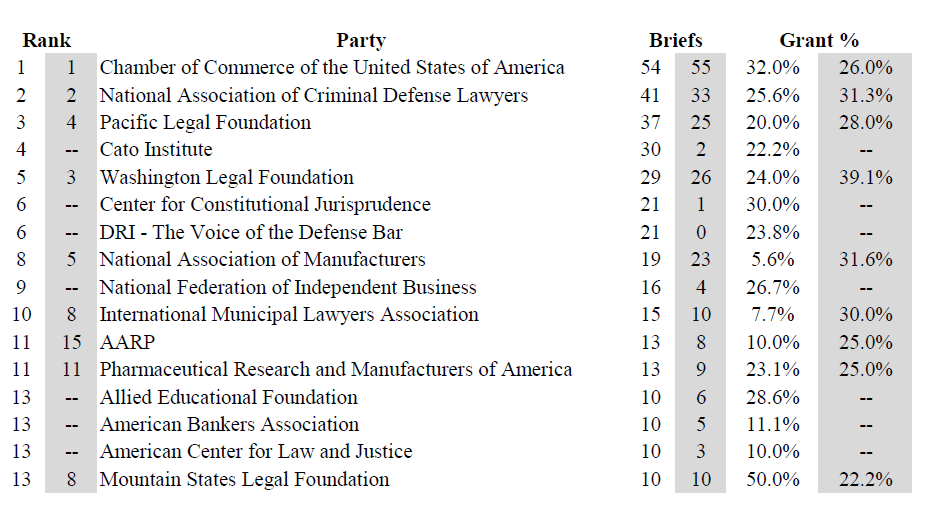

And just who are the Sweet Sixteen this time around? Here’s the list, with figures from five years ago in gray.

A more detailed data table is available here.

The Chamber of Commerce’s continued dominance is immediately apparent. Not only did the Chamber once again file the most briefs, but it had the second-highest success rate of the Sweet Sixteen. In fact, it was one of only two members of that top group to improve its success rate from five years ago.

The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers likewise held onto its second-place perch, contributing to the considerable stability at the top of the leaderboard. Four of the top five amici from five years ago retained a top-five ranking.

The newest top-five filer, however, was not on the leaderboard at all five years ago. The Cato Institute, like several other new entrants to the Sweet Sixteen, went from being a negligible player in the cert. arena five years ago to being a consistent presence today. It is difficult to explain the dramatic boosts in several organizations’ tallies (e.g., Cato, the Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, DRI) without imagining that, at some point in the last five years, they fundamentally reassessed how they could most effectively influence the Court.

The fresh vigor from those groups displaced former Sweet Sixteeners like the Association of American Railroads, the National Association of Home Builders, the National League of Cities, the Council on State Taxation, the Product Liability Advisory Council, and the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press, all of which finished just outside this year’s leaderboard, having filed seven to nine briefs apiece.

Overall, the ideological cast of the new entrants is more conservative, anti-regulatory, and pro-business than that of those they replaced. To varying degrees, all seven of the new entrants have conservative profiles, whereas several of those left off the list this year, like the Society of Professional Journalists and the National League of Cities, have no obvious ideological bent. Five years ago, I wrote that “the list of top amici is dominated by pro-business and anti-regulatory groups—such groups hold over half the slots in the top sixteen.” Now they hold over three-quarters.

While the conservative groups have stepped up their game, the liberals are still nowhere to be found. Five years ago, I noted that the ACLU had filed only two cert.-stage amicus briefs; five years later, it failed even to match that tally. When I talked to the ACLU’s legal director for the Slate article, he told me that the ACLU had made an “organizational decision not to file cert.-stage amicus briefs, except in extraordinary circumstances,” a strategy that does not appear to have changed. (He said it was simply about allocating resources and not about keeping a low profile on issues that might not fare well before the Roberts Court.) There are a few liberal prospects creeping up the ranks, such as the Innocence Network and the Constitutional Accountability Center, making their mark with seven briefs each. But rising right alongside them are conservative counterweights like the Eagle Forum Education & Legal Defense Fund and the American Civil Rights Union. My data indicate that, as the Court shapes its docket, it hears conservative voices far more often than liberal ones, and the disparity is growing.

I conclude this post with the same caveat I gave last time: “the influence of a cert.-stage amicus brief should not be overestimated from the success percentages of the top sixteen groups,” because at least some of the petitions they supported would have been granted regardless. But, I pointed out, research has “closed in on a causal link between [cert.-stage] amici and the Justices granting cert.” Indeed, since that post, newresearch has reinforced earlier findings about the independent influence of cert.-stage amicus briefs in the Justices’ decision making. The briefs matter, a lesson that more organizations appear to learn each year.

This post was written by an attorney in the Appellate Section of the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of Justice.

Posted in Analysis