CASE PREVIEW

Roe v. Wade hangs in balance as reshaped court prepares to hear biggest abortion case in decades

on Nov 29, 2021 at 8:00 am

When he ran for president in 2016, then-candidate Donald Trump promised to nominate Supreme Court justices who would vote to end the constitutional right to an abortion. During his four years in office, Trump placed three justices – Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett – on the court, cementing a 6-3 conservative majority. With that majority in place, conservatives hope, and liberals fear, that the court will renounce nearly five decades of abortion jurisprudence and overturn the landmark rulings of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which is scheduled for oral argument on Wednesday, the justices have been asked to do just that.

If the court were to overturn Roe and Casey, access to abortion in America would shrink dramatically and immediately. Twenty-one states have laws in place that would ban all or nearly all abortions if Roe and Casey fell. And even if the court does not formally overturn Roe and Casey, a decision weakening those precedents would permit new abortion restrictions, perhaps including bans on some early-stage abortions.

Wednesday’s argument in Dobbs, which involves a Mississippi ban on almost all abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy, comes 30 days after the court heard arguments in another consequential abortion controversy: a pair of challenges to a six-week abortion ban that took effect in Texas on Sept. 1. In the Texas cases, the justices will decide whether abortion providers or the federal government can sue to block the law’s unusual private-enforcement structure. The Texas cases, however, do not formally present the question of whether Roe and Casey should remain valid. In Dobbs, Mississippi and its supporters are urging the court to answer that question with a full-throated “no.”

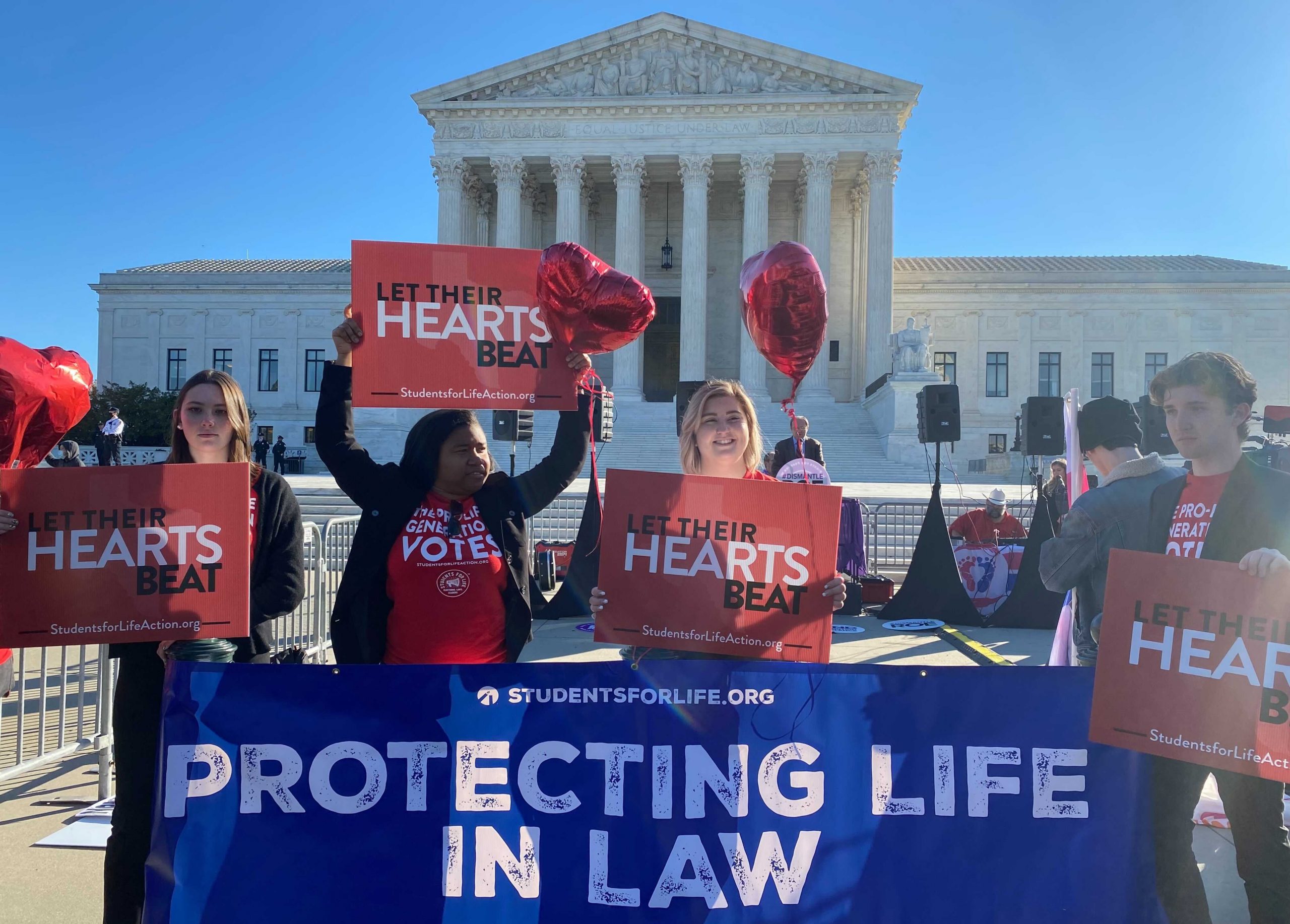

Supporters of abortion rights protest on Nov. 1, 2021. (Katie Barlow)

The Mississippi law and the court’s abortion precedents

The Mississippi law at the heart of the case is known as H.B. 1510 or the Gestational Age Act. Passed in 2018, it bans almost all abortions after 15 weeks: It carves out exceptions for medical emergencies and cases involving a “severe fetal abnormality,” but it does not make exceptions for rape or incest.

Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the only licensed abortion provider in the state, went immediately to federal court to challenge the law, arguing that it is unconstitutional under the Supreme Court’s cases. In Roe, which was decided in 1973, the court held that the 14th Amendment’s due process clause includes a right to privacy that protects the decision to have an abortion. The court also adopted a trimester framework: During the first trimester, states cannot interfere with the decision to have an abortion; during the second trimester, states may adopt reasonable health regulations but cannot ban abortion; and during the third trimester, states may ban abortion except when the procedure is necessary to protect the life or health of the patient.

Nineteen years later, in Casey, the court reaffirmed the “essential holding” of Roe – states cannot ban abortion before viability, the point at around 24 weeks of pregnancy when a fetus can survive outside the womb. Casey, however, replaced the trimester framework with the so-called undue-burden test. Under that test, states may restrict abortion at all stages of pregnancy, even the first trimester, so long as the restriction does not impose an “undue burden” or “substantial obstacle” on the right to obtain a pre-viability abortion.

Because the Mississippi law bans nearly all abortions after 15 weeks (well before the point of viability), a federal district court blocked the state from enforcing the law. After the conservative U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit upheld that ruling, the state came to the Supreme Court, asking the justices to weigh in. The justices considered the state’s petition at 13 consecutive private conferences – an unusually high number – before finally announcing in May that they would hear the case.

Mississippi’s arguments

In its petition for review last year, Mississippi initially told the justices that the questions in its case “do not require the Court to overturn Roe or Casey.” But by the time the state filed its brief on the merits in July, it made an explicit plea to overrule those precedents, describing them as “unprincipled decisions that have damaged the democratic process, poisoned our national discourse, plagued the law – and, in doing so, harmed this Court.” Reversing Roe and Casey would not prohibit abortions, the state stresses; instead, it would just “let the people resolve the issue themselves through the democratic process.”

Mississippi acknowledges that it must overcome the principle of “stare decisis” – the idea that courts should normally follow their prior precedent. But here, the state insists, the “stare decisis case for overruling Roe and Casey is overwhelming.” As a general matter, the state observes, stare decisis is “at its weakest” when courts are interpreting the Constitution, because the democratically elected branches have no recourse (short of a constitutional amendment) to correct a court’s erroneous constitutional interpretation. (By contrast, legislatures can pass new laws if they disagree with a court’s interpretation of a statute.)

Making its case for why stare decisis should not apply to Roe and Casey, the state begins by describing both decisions as not simply wrongly decided but as “egregiously wrong.” There is no right to an abortion in the text of the Constitution, nor is there any general “right to privacy,” Mississippi argues.

The cases are also “hopelessly unworkable,” the state asserts, because applying a heightened constitutional test to abortion restrictions (as Roe and Casey require) hasn’t made review of those restrictions more predictable or clear. The Casey undue-burden test does not give enough weight to the state’s interests in preserving unborn life, protecting maternal health, and upholding the ethics of the medical profession, Mississippi argues.

The cases should also be overturned, Mississippi writes, because Roe is based on a set of factual assumptions “that is decades out of date” – the idea that an unwanted pregnancy would ruin a woman’s life. Birth control and adoption are now readily available, the state notes, and a woman can have both a career and a family. Advances in science also mean, the state observes, that we know more about what the fetus looks like during pregnancy and when it can feel pain.

The state tells the justices that no one could have or should have relied on Roe and Casey in a way that would now weigh against overturning them. The justices have been deeply divided in cases involving abortion, the state notes, and both Congress and the states have considered or even enacted laws intended to test or overturn Roe. Moreover, Mississippi adds, abortion does not implicate reliance interests “in the traditional sense at all” because it is generally “an unplanned response to … unplanned activity.” If Roe and Casey are overturned, the state suggests, reproductive planning “could take virtually immediate account of” that change.

Mississippi attributes broader long-term effects to Roe and Casey, arguing that the rulings “have inflicted significant damage” to the Supreme Court by taking abortion off the table for public debate and giving it special treatment from the courts. Leaving the two cases in place, the state suggests, “harms this Court’s legitimacy”; by contrast, the state emphasizes, overruling them would affirm that “the Constitution leaves most issues,” including abortion, “to the people.”

If Roe and Casey are overturned, the state continues, then the Mississippi law is subject to a less searching constitutional test, known as rational-basis review. The law can easily pass that test, the state contends, because of the state’s legitimate interests in restricting abortions.

The state offers an alternative argument that stops short of overruling Roe and Casey but would still leave its 15-week abortion ban in place. Even if the Constitution does somehow protect a right to abortion, the state argues, nothing suggests it should be linked to viability. Viability is an artificial distinction, the state asserts, because an infant will “be highly dependent on others for survival” after either viability or birth. And if viability is removed from the equation, the state reasons, the law can survive even under heightened scrutiny. The state notes that the clinic in this case is the only abortion provider in Mississippi, and it provides abortions only up to the 16th week of pregnancy, so a ban on abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy does not impose an “undue burden” on the right to obtain an abortion in the state.

The clinic’s arguments

Jackson Women’s Health Organization attempts to cast doubt about whether the justices can even consider the state’s request to overrule Roe and Casey. The clinic notes that the state’s original petition did not seek that outcome and only mentioned the possibility in a single footnote. But the clinic also counters the state’s contention that leaving Roe and Casey in place would undermine the court’s legitimacy. It warns the justices that “[u]nless the Court is to be perceived as representing nothing more than the preferences of its current membership, it is critical that judicial protection hold firm absent the most dramatic and unexpected changes in law or fact.” There have been no such changes, the clinic underscores. “To the contrary,” the clinic writes, “two generations – spanning almost five decades – have come to depend on the availability of legal abortion, and the right to make this decision has been further cemented as critical to gender equality.”

The clinic characterizes Casey as “precedent on top of precedent – that is, precedent not just on the issue of whether the viability line is correct, but also on the issue of whether it should be abandoned.” It too turns to the question of stare decisis, describing the question before the court as “whether Casey’s analysis of the constitutional and institutional considerations was ‘egregiously wrong’” – which, the clinic assures the justices, it was not.

Mississippi is simply wrong, the clinic writes, that there is no support in the Constitution for the right to an abortion. It doesn’t matter that the specific words “abortion” or “pregnancy” don’t appear in the document, the clinic stresses. The “key insight of Casey and Roe is that the decision whether to end a pregnancy has deep constitutional roots in the fundamental rights to body integrity and personal autonomy in matters of family, medical care, and faith.”

The Supreme Court doesn’t need to consider the application of the undue-burden test here, the clinic contends, because this case involves a ban on, rather than regulation of, abortions before viability. And the viability rule, the clinic argues, is a workable one that federal courts have applied “with remarkable uniformity and predictability for five decades.” The court in Casey acknowledged that viability could move earlier, but stressed that a change wouldn’t affect the viability rule itself. But in any event, the clinic emphasizes, it is undisputed in this case that viability occurs around 23 or 24 weeks – the same window as when Casey was decided nearly 30 years ago.

The clinic pushes back against the state’s argument that the underlying factual premises of Roe and Casey have changed. If anything has changed, the clinic suggests, it is that abortions have become even safer than they were when those cases were decided. And the clinic dismisses Mississippi’s claims about changes in society to prevent and accommodate pregnancy as “false and paternalistic.” The right before the court, the clinic insists, is the “ability to decide if, when, and how many children to bear.”

The clinic rejects the state’s alternative argument, telling the justices that “any abandonment of” the viability rule “would be no different than overruling Casey and Roe entirely.” If the viability rule is discarded, the clinic warns, it would result in “attempts by half the states in the Nation to forbid abortion entirely, and a judiciary left without tools to manage the resulting litigation.”

Stare decisis and the Kavanaugh test

The justices are likely to be divided in their ruling, and even the decision to take up the case was a significant one that apparently generated internal debate. Mississippi’s petition for review was first distributed for the justices to consider at their conference on Sept. 29, 2020, but the justices did not grant review until May 2021.

The posture in which the case reached the Supreme Court is also noteworthy. Unlike other abortion cases in recent terms, in which abortion providers came to the Supreme Court after lower courts had upheld laws making it more difficult for doctors to perform abortions, in this case the state came to the Supreme Court after lower courts struck down the ban on abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy. The justices could have turned the case down, perhaps over a dissent by one or more of the conservative justices, but the decision to hear the case on the merits means that there were at least four votes to hear the case; it also suggests that those justices feel confident that there are at least five to uphold the law.

One of those key votes is likely to be Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who in his 2018 confirmation hearing described Roe as “settled as precedent” and noted that it had been “reaffirmed many times,” while he characterized Casey as “precedent on precedent.” Last year, in Ramos v. Louisiana, the court ruled that the Sixth Amendment establishes a right to a unanimous jury that applies in both federal and state courts, overturning a prior ruling from 1972. Kavanaugh wrote a concurring opinion in which he outlined how, in his view, stare decisis applied to the case. He stressed that, “to overrule a constitutional precedent, the Court requires something ‘over and above the belief that the precedent was wrongly decided.’” He focused on what he described as three “broad considerations”: whether the prior decision is “egregiously wrong”; whether it has caused negative consequences, either in the law or in the real world; and whether people have relied on the prior decision, so that overruling it would upset their expectations. Although Kavanaugh’s opinion focused on the unanimous-jury question, it was no doubt written with future cases, particularly abortion cases, in mind.

Implications beyond abortion

If the justices overturn Roe and Casey, the Guttmacher Institute estimates that 26 states (including Mississippi) will implement complete bans on abortion. Although the stakes in the case are thus obviously high, Mississippi takes pains to assure the justices that overruling Roe and Casey would not have ripple effects beyond abortion rights. It distinguishes abortion from other constitutionalized privacy interests, such as interracial marriage and same-sex marriage, saying that those interests – unlike abortion – do not involve the “purposeful termination of a potential life.”

But a “friend of the court” brief supporting the state argues that the effects would be much more expansive than Mississippi suggests. The brief filed by Texas Right to Life (whose counsel of record, Jonathan Mitchell, was the architect of Texas’ six-week abortion ban) tells the justices that the court’s decision in Loving v. Virginia, establishing the right to interracial marriage, would survive if Roe were overruled because the Civil Rights Act of 1866 “provides all the authority needed” to strike down a state law banning interracial marriage. However, the group adds, the court’s decisions in Lawrence v. Texas, striking down a Texas law prohibiting gay sex, and Obergefell v. Hodges, holding that the Constitution guarantees a right to same-sex marriage, would necessarily fall because they are “as lawless as Roe.”

With so much to consider, two things are virtually certain: Wednesday’s oral argument will last well beyond the 70 minutes that the court has allotted, and the justices will not announce their decision in the case until much later in the term.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.