Opinion analysis

Court holds that city’s refusal to make referrals to faith-based agency violates Constitution

on Jun 17, 2021 at 1:04 pm

This article was updated on June 17 at 6:52 p.m.

In a clash between religious freedom and public policies that protect LGBTQ people, the Supreme Court ruled Thursday that Philadelphia violated the First Amendment’s free exercise clause when the city stopped working with a Catholic organization that refused to certify same-sex couples as potential foster parents.

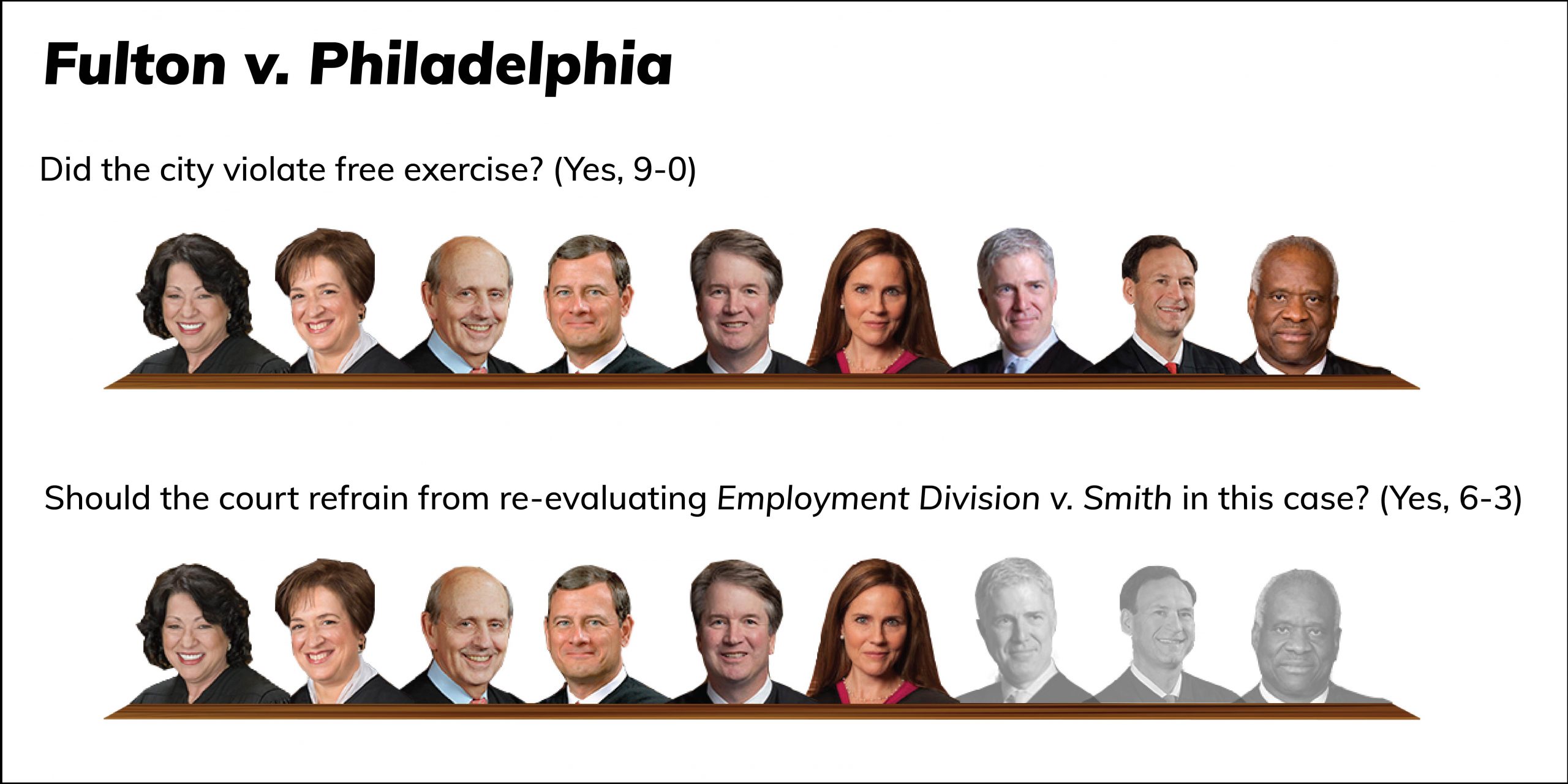

The ruling was a victory for Catholic Social Services, an organization associated with the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, and two foster parents, who alleged that Philadelphia’s refusal to make foster-care referrals to CSS discriminated against the group because of its religious beliefs about traditional marriage. But the decision fell short of the broad endorsement of religious freedom that the challengers had sought. While the justices unanimously agreed with CSS and the foster parents that the city’s action was unconstitutional, a six-justice majority left intact the Supreme Court’s 1990 decision in Employment Division v. Smith, which held that government actions usually do not violate the free exercise clause as long as they are neutral and apply to everyone.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court, in an opinion that was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. Barrett wrote a concurring opinion that Kavanaugh joined in full and Breyer joined except for the first paragraph. Justice Samuel Alito wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment – that is, agreeing with the result that the court reached, if not necessarily its reasoning. His opinion was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch. Gorsuch wrote his own opinion concurring in the judgment, which Thomas and Alito joined.

The case began in 2018, after Philadelphia’s city council passed a resolution that condemned “discrimination that occurs under the guise of religious freedom” and instructed the city’s Department of Human Services, which contracts with private organizations to place children in foster homes, to change its contracting practices. In the days that followed the resolution, the city stopped all referrals to CSS.

CSS and two foster parents, Sharonell Fulton and Toni Lynn Simms-Busch, went to federal court and sought a court order requiring the city to resume referrals to CSS. They contended that the city’s decision to cut off referrals violated several different parts of the First Amendment: the free exercise clause, which protects religious belief and expression; the establishment clause, which (among other things) prohibits the government from favoring non-religion over religion; and the free speech clause. A federal district court turned them down, ruling that the city’s policy passed muster under Smith. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit affirmed, finding no sign that the city had discriminated against CSS because of its religious beliefs.

The Supreme Court reversed. In his opinion for the court, Roberts began by observing that it was “plain” that the city’s actions had burdened CSS’s exercise of its religion, by requiring it to choose between “curtailing its mission or approving relationships inconsistent with its beliefs.” The question before the court, Roberts continued, was whether the Constitution allows the city to impose that burden.

And although CSS had asked the court to overrule Smith, Roberts noted, there was no need for the court to consider that question, because the city’s policy is not “generally applicable.” The provision in the city’s standard foster-care contract that CSS is accused of violating, which bars rejection of prospective foster-care parents based on their sexual orientation, includes a system of individual exemptions that the commissioner of the city’s Department of Human Services can grant in her “sole discretion,” Roberts emphasized.

It doesn’t matter, Roberts added, that the commissioner has never actually granted an exception. The problem, Roberts made clear, is the existence of a “formal mechanism for granting exceptions” in the first place, because such a scheme “‘invite[s]’ the government to decide which reasons for not complying with the policy are worthy of solicitude.”

Roberts also briefly considered, but rejected, the city’s argument that CSS’s refusal to certify same-sex couples violates a city ordinance prohibiting discrimination by public accommodations. The ordinance does not apply to CSS, Roberts reasoned, because foster-care agencies “do not act as public accommodations in performing certifications.”

Because the city’s contracting policy is not “generally applicable” under Smith, the policy is subject to the most stringent constitutional test, known as strict scrutiny, Roberts explained. He concluded that it cannot pass that test. The city, Roberts wrote, has not shown that its goals of maximizing the number of foster families and minimizing the city’s legal liability will be jeopardized by giving CSS an exemption from the non-discrimination policy. To the contrary, Roberts suggested, “including CSS in the program seems likely to increase, not reduce, the number of available foster parents.” Roberts acknowledged the city’s “weighty” interest in the “equal treatment of prospective foster parents and children,” but he concluded that it was not sufficient to “justify denying CSS an exception for its religious exercise,” especially when the city has a system of exemptions.

CSS, Roberts concluded, “seeks only an accommodation that will allow it to continue serving the children of Philadelphia in a manner consistent with its religious beliefs.” CSS does not, Roberts emphasized, “seek to impose those beliefs on anyone else.”

Barrett, who joined the Roberts majority opinion in full, filed a short concurring opinion that was joined by Kavanaugh and (except for the first paragraph) Breyer. CSS and its supporters, Barrett acknowledged, have “made serious arguments that Smith ought to be overruled.” But in this case, she continued, “the same standard applies regardless whether Smith stays in place.” Therefore, she concluded, there was no reason for the court to “decide in this case whether Smith should be overruled, much less what should replace it.”

In his 77-page concurring opinion, Alito criticized the narrowness of the court’s ruling, writing that Thursday’s decision “might as well be written on the dissolving paper sold in magic shops.” Philadelphia, Alito suggested, could easily sidestep the decision simply by getting rid of the exemption system, and the ruling “provides no guidance” for similar disputes elsewhere in the country.

Alito then turned to the court’s decision in Smith, which he characterized as a “severe holding” that is “ripe for reexamination.” The ordinary meaning of the Constitution’s free exercise clause, Alito contended, is that it bars any laws that “forbid” or “hinder” “unrestrained religious practices or worship.” By contrast, Alito observed, Smith interpreted the free exercise clause as an anti-discrimination provision: It bars federal and state governments from restricting “conduct that constitutes a religious practice for some people unless it imposes the same restriction on everyone else who engages in the same conduct.” But if equal treatment was the goal of the free exercise clause, Alito suggested, the drafters of the First Amendment would have used more precise language to make that clear.

Alito acknowledged the doctrine of stare decisis, the principle that the court should rarely overrule its own precedent. But he nevertheless laid out the case to overrule Smith. Several of the factors that the court often considers when deciding whether to overrule its past decisions “weigh strongly against Smith,” Alito contended. For example, the decision is a “methodological outlier” that “looked for precedential support in strange places,” he suggested,” and it is “tough to harmonize” with other precedents. Moreover, he added, courts have experienced a variety of “serious problems” in applying Smith. On the other hand, Alito argued, there is virtually nothing to recommend keeping Smith in place.

Alito closed by complaining that, after all of the time and attention devoted to the case, the Supreme Court had issued only “a wisp of a decision that leaves religious liberty in a confused and vulnerable state. Those who count on this Court to stand up for the First Amendment have every right to be disappointed,” Alito concluded. He added, “as am I.”

In his opinion concurring in the judgment, Gorsuch noted that if the court had overruled Smith, as Alito had suggested, “this case would end today.” Instead, Gorsuch objected, “the majority’s course guarantees that this litigation is only getting started.” The city will resist working with CSS as long as CSS refuses to certify same-sex couples, Gorsuch posited, and Thursday’s decision will allow the city to try to avoid doing so – for example, by rewriting its contract. And the effects of the court’s decision will not be limited to CSS, Gorsuch stressed: “Individuals and groups across the country will pay the price — in dollars, in time, and in continuing uncertainty about their religious liberties.”

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.