Opinion analysis

Justices decisively reject imposing issue exhaustion on Social Security claimants

on Apr 23, 2021 at 4:18 pm

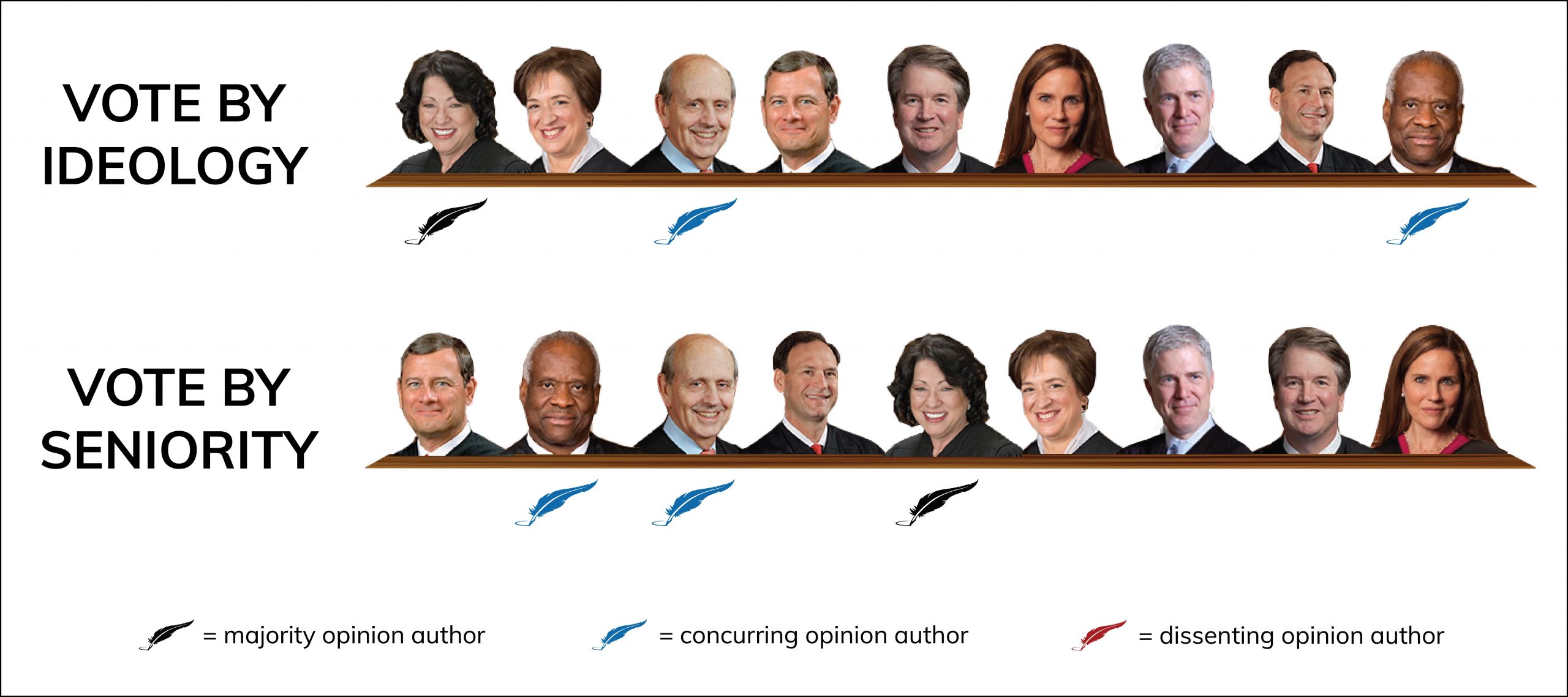

The Supreme Court on Thursday firmly rejected the government’s request that the court impose an “issue-exhaustion” requirement on Social Security claimants. In Carr v. Saul (consolidated with Davis v. Saul), all parties agreed that those claimants must take their claims first to the Social Security Administration – and these claimants did that. The question was whether they must raise, before the agency, all of the issues they will eventually raise when they get to court. In this case, for example, the claimants in agency proceedings from 2013 to 2015 did not know that a 2018 decision of the Supreme Court would invalidate the SSA’s process for appointing administrative law judges, and so they did not complain about that process before the agency. The lower courts held that because they did not have the prescience to raise that issue before the agency, they could not raise it now, and thus would get no remedy for the denial of their claims by an unlawful administrative law judge. Although four of the justices disagreed with minor aspects of the opinion for the court by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, all of the justices rejected the rulings imposing that requirement.

Sotomayor’s opinion starts by noting that “[a]dministrative review schemes commonly require parties to give the agency an opportunity to address an issue before seeking judicial review of that question,” and emphasizes that those requirements “[t]ypically … are creatures of statute or regulation.” Because there is no statute or regulation in this case, the government was seeking a “judicially created issue-exhaustion requirement.” Sotomayor goes on to explain that the courts typically assess the propriety of judicially created exhaustion requirements based “on the degree to which the analogy to normal adversarial litigation applies in a particular administrative proceeding.” Prior cases have held that the “critical feature that distinguishes adversarial proceedings from inquisitorial ones is whether claimants bear the responsibility to develop issues for adjudicators’ consideration.”

Sotomayor starts from “the baseline set” by the court’s earlier decision in Sims v. Apfel, which permitted claimants to raise issues in court that they did not raise before the agency’s Appeals Council. The same regulations at issue in Sims applied to this case, which considered the slightly different question of whether claimants must exhaust issues before the agency’s unlawfully appointed administrative law judges. Sotomayor quotes provisions of those regulations that, among other things, contemplate an “informal, nonadversary” hearing, obligate ALJs to “loo[k] fully into the issues,” and suggest that in requesting a hearing it should take only “10 minutes to read the instructions, gather the facts, and answer the questions.”

Those provisions suggest that the holding of Sims “applies equally to ALJ proceedings.” Sotomayor stops short, though, of basing the decision directly on Sims. Rather, she explains, she relies on “additional considerations” related to the appointments-clause challenges presented here, cautioning in a footnote that “the scales might tip differently” for other types of claims. For the claims presented here, it is important that agency adjudications “are generally ill suited to address structural constitutional challenges.” That is especially important when it would be futile to present them to the agency: “It makes little sense to require litigants to present claims to adjudicators who are powerless to grant the relief requested.” Given the plain futility of raising the appointments clause in the claimants’ agency hearings, Sotomayor concludes that the claimants are entitled to relief in the lower courts.