Argument analysis

Justices employ full-court press in dispute over college athlete compensation

on Mar 31, 2021 at 5:33 pm

With just a few days until college basketball begins its “Final Four” to crown the men’s and women’s champion, the attention at the Supreme Court on Wednesday turned to college sports. The spotlight was often harsh, with several justices openly criticizing the state of elite college sports – and, by extension, efforts by the National Collegiate Athletic Association to defend restrictions on compensation for college athletes on the ground that they preserve amateurism. But at the same time, the justices expressed concern that a decision in favor of the college football and basketball players who are challenging the NCAA’s eligibility rules could eventually destroy college sports altogether.

The case before the court was filed as a class action against the NCAA and the major athletic conferences in 2014, arguing that the NCAA’s restrictions on eligibility and compensation violate federal antitrust laws by barring the athletes from receiving fair-market compensation for their labor. A federal district court in California ruled that the NCAA could restrict benefits that are unrelated to education (such as cash salaries), but it prohibited the NCAA from limiting education-related benefits (such as free laptops or paid post-graduate internships). The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit upheld that decision, setting the stage for the Supreme Court’s review in NCAA v. Alston.

Lawyer Seth Waxman represented the NCAA. He told the justices that for over 100 years, the “distinct character” of college sports is that it has been played by students who are amateurs, which means that “they are not paid for their play.” Because that differentiation between college sports and professional sports promotes competition, Waxman continued, rules like the ones at the center of this case that are “reasonably designed to preserve amateurism as the NCAA has defined it” should be upheld.

Waxman’s focus on amateurism drew a barrage of questions from the justices. Chief Justice John Roberts asked Waxman about a current rule allowing colleges and universities to pay up to $50,000 to obtain a $10 million insurance policy to protect the future earnings of college athletes in case they are injured before they can become professionals. That, Roberts told Waxman, sounds like “pay for play”; the school is buying the policy for college athletes so that they will remain in school rather than going pro.

Justice Clarence Thomas, an avid fan of the University of Nebraska football team, observed that it was “odd” that, despite the NCAA’s focus on amateurism, coaches’ salaries have “ballooned” in college sports. (One “friend of the court” brief in the case noted that, in 2017, college football or basketball coaches were the highest-paid state employees in 39 states, with 34 of them earning more than $2 million.)

Justice Samuel Alito suggested that the circumstances of major-college athletics “paint a pretty stark picture” in which powerhouse programs bring in billions of dollars and pay enormous salaries to coaches, but the athletes themselves put in long hours of training, at significant cost to their studies, resulting in “shockingly low” graduation rates. The athletes, Alito concluded, are “recruited, they’re used up, and then they’re cast aside.”

Waxman pushed back, reminding Alito that there is a “healthy debate” in legislatures around the country about whether college athletes should be paid. But if they are paid, he cautioned, it will require them to spend more time on sports, rather than less.

Justice Elena Kagan came at the issue from a slightly different angle. Waxman’s talk about amateurism is “awfully high-minded,” she admonished. But what this case boils down to, she suggested, is that schools that are naturally competitors have all gotten together and used their power to fix salaries for college athletes at extremely low levels.

When Waxman responded that amateur college sports are not “some differentiated product that has just been created,” but were instead “created 116 years ago … to restore integrity and the social value of college athletics,” Kagan was unmoved. “You can only ride on the history for so long,” she replied. A lot has changed in college sports, Kagan said, even since the Supreme Court’s 1984 decision in NCAA v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma, on which the NCAA relies for the proposition that rules intended to preserve amateurism in college sports are subject to a more deferential standard of review.

But it may have been Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who coaches his daughter’s basketball team and who tried out unsuccessfully for the basketball team at Yale when he was an undergraduate there, whose questions and comments were most hostile to the NCAA. Kavanaugh told Waxman that he was starting from the premise that U.S. antitrust laws “should not be a cover for exploitation of the student-athletes.” Kavanaugh then summarized the case as one in which the schools were conspiring with their competitors “to pay no salaries to the workers who are making the schools billions of dollars on the theory that consumers want the schools to pay their workers nothing.” Such a scenario, Kavanaugh concluded, “seems entirely circular and even somewhat disturbing.”

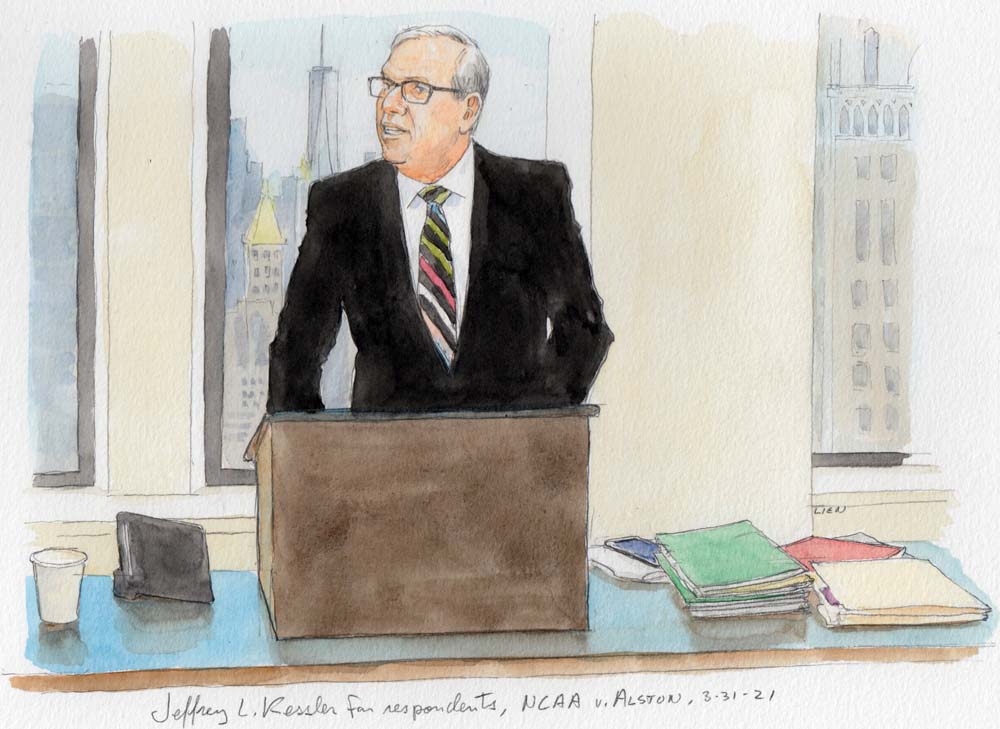

Representing the college athletes, attorney Jeffrey Kessler told the justices that the NCAA has repeatedly tried to fend off antitrust challenges by predicting that “economic competition among its member schools would destroy consumer demand for college sports.” But each time the courts struck down challenged restrictions, Kessler explained, “the courts were correct” and “[d]emand for college sports has continued to flourish.”

Despite Kessler’s assurances, both he and Acting U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar, who argued on behalf of the Department of Justice as a “friend of the court” supporting the athletes, faced a series of questions that centered on two topics related to one theme: What effect would a ruling in favor of the athletes ultimately have on college sports and the judiciary’s role in them? The first category of questions focused on the district court’s ruling that schools can provide up to $5,980 per year to a college athlete as a benefit just for being a member of a college team. Thomas asked Kessler about a scenario in which a survey found that consumers would not object to athletes receiving up to $20,000 per year. What, Thomas queried, happens then? Will we be back in court again?

Kessler responded that the $5,980 limit is the same one imposed by the NCAA on payments by schools to college athletes to recognize their play on the field, and he stressed that the NCAA “did not see any damage to its product” from allowing such awards.

Thomas suggested that such awards could create an imbalance, as “upper-level schools” like Alabama and Nebraska could pay such benefits and recruit high-quality players away from schools with fewer resources.

Kessler countered that an imbalance already exists, and he reminded the justices that the district court’s ruling doesn’t require any school to pay benefits; the decision “simply said the NCAA can’t prohibit it, but the conferences can.” Indeed, he noted, some athletic conferences – like the Patriot League, whose members include the College of the Holy Cross, from which Thomas graduated in 1971 – don’t allow athletic scholarships.

Kagan wondered aloud whether the $5,980 limit wasn’t an arbitrary award that the court “should react badly to.” But like Kessler, Prelogar reiterated that “the key here is to recognize that this is just making the students eligible for awards up to that amount.” Nothing in the district court’s ruling, Prelogar emphasized, suggests that every student automatically gets that money just for playing on a team. Prelogar was making her argument debut as President Joe Biden’s acting solicitor general, though she has previously argued before the court seven times as an attorney in the SG’s office.

Kavanaugh asked Prelogar to respond to Waxman’s assertion that, if the district court’s ruling is allowed to stand, the definition of “education-related benefits” would be “stretched,” turning “very quickly” into “just an automatic payment” to college athletes.

Prelogar resisted that assertion, telling Kavanaugh that the court of appeals considered this argument and made clear that the district court’s order cannot be accurately interpreted to allow sham payments. “The district court here,” Prelogar told Kavanaugh, “was clearly focused on legitimate educational benefits,” so that a situation like the one that the NCAA cautioned against in its brief – a $500,000 “internship” at a sneaker company – wouldn’t qualify. And if there’s any confusion, Prelogar added, the district court specifically said that the NCAA can define what counts as an education-related benefit.

Justice Stephen Breyer told Kessler that this was a “tough case” for him, including because he worried “a lot about judges getting into the business of deciding how amateur sports should be run.” And depending on how the court rules, Breyer noted, it could affect other areas of antitrust law as well. Roberts echoed this point in a question for Prelogar, suggesting that although the athletes and the DOJ portray the district court’s ruling as a “modest” one, “there will be a wide number of rules that are subject to challenge” in later cases.

Prelogar tried to assure the justices, telling them that “the legal standards themselves guard against micromanagement,” but Waxman returned to this theme during his rebuttal. “Once courts start drawing their own lines,” he argued, “perpetual litigation and judicial superintendence are inevitable.” But it wasn’t clear whether these concerns would be enough to overcome the justices’ clearly significant concerns about the restrictions that the NCAA sought to defend on Wednesday. A decision is expected by summer.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.