Argument analysis: Justices divided on agency deference doctrine

on Mar 27, 2019 at 4:07 pm

The Supreme Court heard oral argument this morning in a dispute over veterans’ benefits that could become one of the most significant cases of the term. Although the case arose when the Department of Veterans Affairs refused to give James Kisor, who served as a Marine during the Vietnam War, benefits for his post-traumatic-stress disorder dating back to 1983, it has morphed into something much bigger. Kisor and his lawyers have asked the justices to overrule a doctrine that Chief Justice John Roberts has described as “going to the heart of administrative law”: the idea that courts should generally defer to a federal agency’s interpretation of its own regulation. After roughly an hour of debate today, the justices were deeply divided in a case in which their ruling could have implications not only for veterans but also for other areas of the law ranging from the environment to immigration.

The doctrine at the center of today’s case is known as Auer deference. It was named after the 1997 case Auer v. Robbins and is also sometimes known as Seminole Rock deference, after the 1945 case Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand Co. The doctrine rests, at least in part, on the idea that a federal agency has more expertise in the subject matter covered by the regulation (and by the law that the agency was interpreting when it issued the regulation), and – as law professor Aaron Nielson wrote three years ago, the agency that wrote a regulation will “know best what it means.”

Arguing for Kisor in the Supreme Court today, attorney Paul Hughes urged the court to overrule the Auer doctrine, which he described as a way around the general requirement that agencies notify the public of proposed regulations and provide an opportunity for comments on those proposed regulations. The lack of an opportunity for the public, and particularly for people or entities who are affected by a regulation, to participate in the process of making the regulations is not, Hughes stressed, “just some speed bump along the administrative process. This matters as a practical matter a great degree.”

The court’s more liberal justices appeared largely unpersuaded by Hughes’ arguments. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg queried why the justices needed to decide the Auer deference question at all if – as the government contends – either the regulation at the center of the dispute is clear or the VA’s reading of the regulation is “by far the better reading” anyway.

Justice Stephen Breyer seemed to believe that federal agencies, rather than federal judges, have expertise in their specific subject matter that makes them better suited to interpret highly technical regulations. He pointed to an example in which the court “deferred to the understanding of the FDA that a particular compound should be treated as a single new active moiety, which consists of a previously approved moiety, joined by a non-ester covalent bond to a lysine group.” Drawing laughter from the gallery, Breyer asked rhetorically, “Do you know how much I know about that?”

And Justice Elena Kagan pressed Hughes about whether it was appropriate for the justices to overrule their past cases when Congress is well aware of the Auer rule and “has repeatedly acted in this sphere and shown no interest whatsoever in reversing the rule that the Court has long established.”

Hughes pushed back, noting that the Supreme Court has recently overruled its prior cases in other contexts in which Congress could have stepped in. That prompted Kagan to observe wryly that “there aren’t very many of those cases. And we take it super-seriously when we do and we need a – I mean we used to – and we need a good reason for it.”

Chief Justice John Roberts chimed in, noting that the Auer rule had been narrowed over the years. He wondered aloud “exactly how much of a change at the end of the day you’re talking about” – which seemed to suggest that he might have fewer concerns about overruling Auer, because Hughes’ proposed rule might not be a significant change from the current rule.

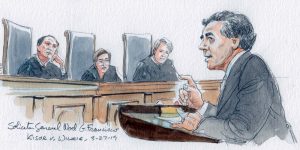

U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco argued on behalf of the federal government. He acknowledged that the Auer doctrine “raises some problems in its applications” but urged the court to keep it in place with some “reasonable limitations” to address those problems.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, who last year joined a dissent from the denial of review by Justice Clarence Thomas that described Auer deference as “constitutionally suspect,” quickly peppered Francisco with a series of questions that left little doubt about Gorsuch’s views on the issue. There are multiple parts to the test that the federal government would have courts apply to determine whether to defer to an agency’s interpretation of its own regulation, Gorsuch told Francisco. “Is that a recipe for stability or predictability in the law,” Gorsuch asked, “or is that a recipe for the opposite?”

Gorsuch spoke even more plainly a few minutes later, when Francisco suggested that the government’s rule would help members of the public who were regulated by a particular agency because they “can rely on the agency” and its interpretation of the regulation, rather than having to go to courts around the country to figure out what the regulation means. “I must say,” Gorsuch told Francisco, “I cast a skeptical eye when the government is worried about private reliance interests,” because “every private party before us” – from the Chamber of Commerce to veterans and immigration lawyers – “says their interests in stability would be better served by eliminating this rule altogether.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh appeared to believe that the better course would be for agencies always to use the notice-and-comment process when making regulations that interpret other regulations. “You said it takes a long time, and that may be a problem with some lower court impediments to notice and comment, I share that concern, but if notice and comment were more efficient, why not just do notice and comment?”

Francisco agreed that the notice-and-comment process “is a very important process,” but he explained that while it is underway, “you’re facing a rule that, by definition, is ambiguous. And you’ve got to figure out what to do with it.”

Kavanaugh later appeared troubled by the idea that, under the government’s theory, a judge might have to defer to an agency’s interpretation of a regulation even if the judge believes that the interpretation “is a really important interpretation, has real effects on many people, and it’s wrong” – just because the regulation is not clear.

In his rebuttal, Hughes stressed that “the appropriate resolution of this case is to overturn Seminole Rock and Auer in their whole because it’s critical to restore the importance of notice-and-comment rulemaking that Congress thought was a critical check to bring democratic accountability to the agencies.” It’s not entirely clear whether Hughes has the five votes he needs to prevail on this point, particularly because the court’s four more liberal justices seemed staunchly opposed to his position, but after today’s argument it certainly seems possible that he does.

A decision in the case is expected by summer.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.

Editor’s Note: Analysis based on transcript of oral argument.