Argument analysis: Searching for the least unnatural reading

on Jan 9, 2019 at 1:10 pm

The second argument on Monday was in Obduskey v. McCarthy Holthus LLP, a case about whether law firms that handle nonjudicial foreclosures are “debt collectors” within the meaning of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. If the argument clarified anything, it’s that the FDCPA is a messy statute.

This case arises from a crowded corner of consumer law involving significant state and federal regulations that do not always play well together. Colorado foreclosure law requires a firm initiating a nonjudicial foreclosure to send a notice that lists various details about the underlying mortgage. McCarthy Holthus LLP, on behalf of its client Wells Fargo, sent Dennis Obduskey such a notice in 2014. Obduskey responded by following the FDCPA’s procedures for disputing a debt. Rather than continuing through the FDCPA process, McCarthy initiated a new nonjudicial foreclosure in 2015. Obduskey then sued McCarthy for allegedly violating the FDCPA and Colorado law.

This case turns on whether the FDCPA covers parties that handle nonjudicial foreclosures. That question turns on three sentences in 15 U.S.C. § 1692a(6):

The term “debt collector” means any person who uses any instrumentality of interstate commerce or the mails in any business the principal purpose of which is the collection of any debts, or who regularly collects or attempts to collect, directly or indirectly, debts owed or due or asserted to be owed or due another. Notwithstanding the exclusion provided by clause (F) of the last sentence of this paragraph, the term includes any creditor who, in the process of collecting his own debts, uses any name other than his own which would indicate that a third person is collecting or attempting to collect such debts. For the purpose of section 1692f(6) of this title, such term also includes any person who uses any instrumentality of interstate commerce or the mails in any business the principal purpose of which is the enforcement of security interests.

The case also turns on how those sentences relate to 15 U.S.C. § 1692f(6):

Taking or threatening to take any nonjudicial action to effect dispossession or disablement of property if—

(A) there is no present right to possession of the property claimed as collateral through an enforceable security interest;

(B) there is no present intention to take possession of the property; or

(C) the property is exempt by law from such dispossession or disablement.

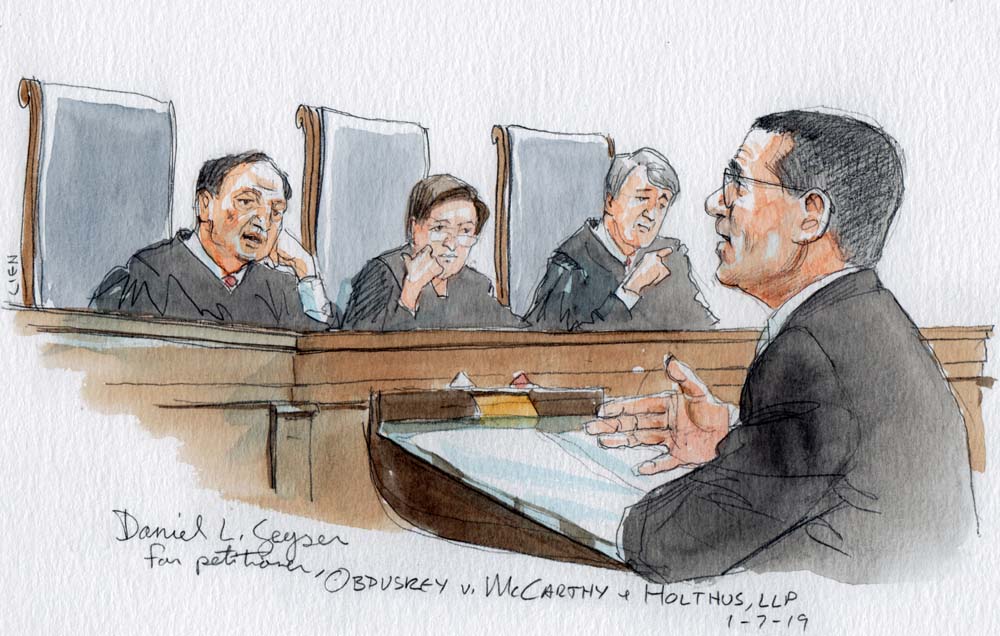

Beginning with the first sentence of Section 1692a(6), Daniel Geyser, representing Obduskey, argued that the FDCPA includes attorneys like McCarthy because nonjudicial foreclosure efforts are “attempts to collect” debt “directly or indirectly.” Several of the justices seemed to find this broad view of debt collection intuitively appealing, but that did not necessarily get them past Section 1692a(f)’s pesky third sentence (“such term … includes any person who uses any instrumentality of interstate commerce or the mails in any business the principal purpose of which is the enforcement of security interests”).

Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh had several questions for Geyser about how to read the first sentence without rendering the third sentence irrelevant. Kavanaugh even probed the statute’s legislative history for the debate about whether those enforcing security interests alone would fall within the definition of debt collectors. In response, Geyser argued that the third sentence of Section 1692a(6) refers to repossession agents who tow cars under the cover of darkness without any effort to communicate with the borrower — the proverbial “repo man.” He described the statute as creating “sort of like a Venn diagram.” On one side, there are “some people who collect debts without enforcing a security interest.” The first sentence of Section 1692a(6) governs those people. On the other side of the diagram, there are “some people who enforce security interests without collecting debts.” The third sentence of Section 1692a(6) governs these people. And in the middle of the overlapping circles there are the people who both collect debts and enforce security interests. Geyser argued that both the first and the third sentences of Section 1692a(6) govern the middle category and that nonjudicial foreclosure agents belong in that category.

To succeed on this theory, Geyser had to draw a line between repossession activity and nonjudicial foreclosure. But that proved difficult. Geyser tried to argue that the notices that foreclosure agents send distinguish them from other repossession agents. But that argument caused Justice Stephen Breyer to chime in that “if we accept what you say, we’d have to say that the Colorado law is illegal.” Neither Breyer nor any of the other justices seemed eager to upend Colorado’s law, especially after Breyer noted that it may offer consumers more protection than the FDCPA.

In the end, the “repo man” example proved problematic for Geyser. When he tried to argue that repossession activity, or even changing locks on an apartment, was enforcing a security interest, not collecting a debt, Gorsuch asked, “Why isn’t that just conceding away the case?” Justice Elena Kagan had several questions about Geyser’s framework as well. She noted that foreclosure and repossession are economically equivalent. She pushed back against Geyser’s Venn diagram, saying that “the grammar of the statute suggests that we not have to kick them out of one or the other” and that “foreclosures are the paradigmatic enforcement of security interests.” And although Justice Sonia Sotomayor seemed more sympathetic than anyone else to Geyser’s argument, she too piled on, saying, “I don’t even know what the repo argument was about in your brief.”

The justices had just as many tough questions for Kannon Shanmugam, who argued for McCarthy, and Jonathan Bond, who argued for the United States as amicus curiae supporting McCarthy. Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts interrogated Shanmugam on why activities had to fall under either the first or the third sentences of Section 1692a(6), especially in light of the word “indirectly,” which could significantly broaden the scope of the statute. Shanmugan argued that some request for payment was essential for foreclosure activity to fall under the first sentence. By way of example, Shanmugam said that McCarthy does not dispute that judicial foreclosures fall within the first sentence when creditors seek deficiency judgments against the borrowers. This did not sit well with Sotomayor. “It is a bit strange,” she said, “to think that Congress intended to cover judicial foreclosures where a judge is supervising the process but not when it’s a non-judge supervised process.”

By the end of Bond’s argument, Kagan and Gorsuch became interested in the relationship between the FDCPA and state law. Bond argued that state law should determine whether any activity is debt collection or enforcement of a security interest. But it was not clear how that approach would work in practice. Kagan pressed Bond about deficiency judgments, asking what would happen if state law allowed creditors to seek such judgments in nonjudicial foreclosures. He had to concede that seeking a deficiency judgment would be debt collection within the scope of the first sentence of Section 1692a(6).

The only consensus to emerge by the end of the argument was that there were many “unnatural” ways to read the statute. Several justices seem sympathetic to Obduskey’s policy argument, but more seem skeptical of his statutory argument. Beyond that, it is hard to make any confident prediction about the result, particularly because Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg intends to participate in the case although she did not attend the argument. Because the justices appear reluctant to do anything that would require significant changes to state foreclosure laws, a narrow opinion seems most likely.

Editor’s Note: Analysis based on transcript of oral argument.