Argument analysis: Drawing a line on privacy for cellphone records, but where?

on Nov 29, 2017 at 2:43 pm

The Supreme Court heard oral argument this morning in an important privacy-rights case. The defendant in the case, Timothy Carpenter, was convicted and sentenced to 116 years in prison for his role in a series of armed robberies in Michigan and Ohio. At his trial, prosecutors introduced Carpenter’s cellphone records, which confirmed that his cellphone connected with cell towers in the vicinity of the robberies. Carpenter argued that prosecutors could not use the cellphone records against him because they had not gotten a warrant for them, but the lower courts disagreed. Today the Supreme Court seemed more sympathetic, although they were clearly uncertain about exactly what to do. As Justice Stephen Breyer put it at one point, “This is an open box. We know not where we go.”

Nathan F. Wessler at lectern for petitioner (Art Lien)

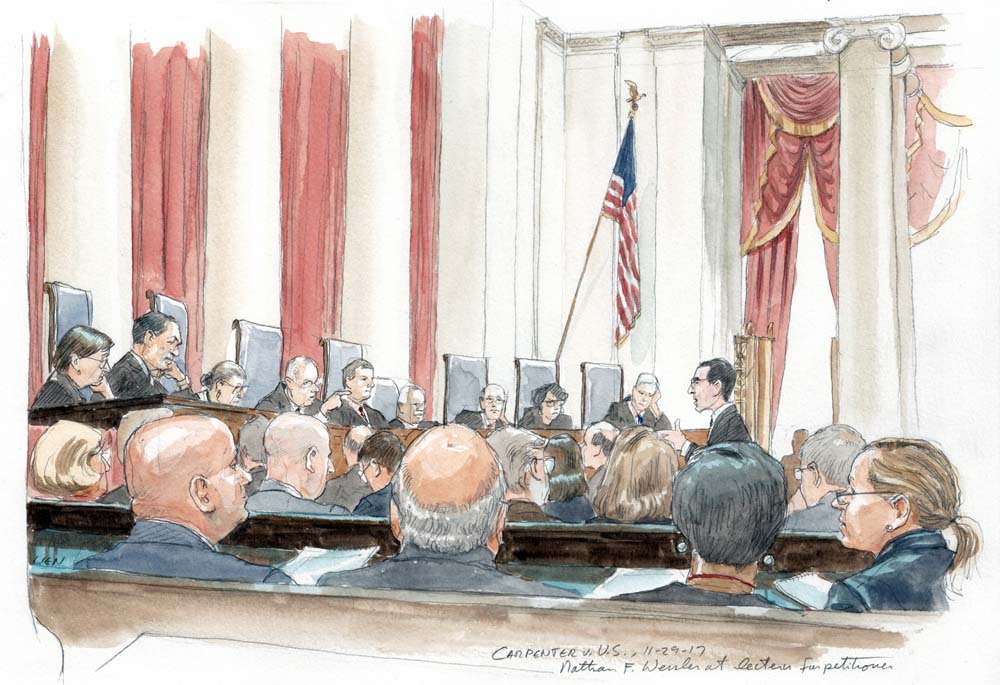

Defending the decisions below, Deputy Solicitor General Michael Dreeben, who took a brief break from his duties working on special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, drew a firm line in the sand. The technology at issue in Carpenter’s case may be new, but the legal principles implicated by the case are not, Dreeben told the justices. The case is governed squarely by the court’s decisions in United States v. Miller and Smith v. Maryland, which embody what is known as the “third-party doctrine”: The Fourth Amendment does not protect records or information that you share with someone else. So Carpenter’s case (and others like it) hinges, Dreeben contended, on how the government got the information. And here, he emphasized, the cellphone providers created the records for their own purposes and gave them to the government; the government did not collect the data itself.

Several justices were skeptical that the case was as simple as Dreeben depicted it. Chief Justice John Roberts pointed out that, in Carpenter’s case, the cellphone provider had not actually generated the records entirely on its own. Instead, Roberts observed, the cellphone records are more like a “joint venture” with the phone’s owner.

Deputy Solicitor General Michael R. Dreeben (Art Lien)

Justice Elena Kagan brought up United States v. Jones, in which the Supreme Court ruled that attaching a GPS device to the car of a suspected drug dealer and using it to track the car’s movements constituted a “search” for purposes of the Fourth Amendment. How is this case different from Jones, she asked Dreeben, in which five justices agreed that society did not expect the government to track a suspect’s every movement for an extended period of time?

Dreeben pushed back, maintaining that Jones involved direct surveillance by the government, while Carpenter’s case involves business records from the cellphone provider. But Kagan appeared unpersuaded, pointing to what she described as an “obvious similarity” between the two cases: reliance on new technology that allows for 24/7 surveillance. Dreeben reiterated that in the case of cell-site records, the government isn’t watching anyone; any “surveillance” comes from the phone company “because people have decided to sign up for cellular service in which it is a necessity … that your phone communicate with a tower and a business record is generated.” And to the extent that a cellphone owner believes that his cellphone records are or should be kept private, Dreeben added, the appropriate institution to address that concern is Congress, rather than the Supreme Court.

Roberts suggested that Dreeben’s argument was inconsistent with the Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in Riley v. California, in which the justices ruled that police must get a warrant before they can search the cellphone of someone who has been arrested. People don’t really have a choice about whether to have a cellphone, Roberts suggested.

Justice Anthony Kennedy seemed to see the question differently, however. He asked Nathan Wessler, who argued on Carpenter’s behalf, whether most people realize that their cellphone providers do have their data. “If I know it, everybody does,” Kennedy said, drawing laughter.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was more sympathetic to Carpenter, and she tried to remind the court of the stakes in the case. Although this case is only about the historical cell-site records, which indicate where a cellphone connected with a tower, she stressed, technology is now far more advanced than it was even a few years ago, when Carpenter was arrested. A provider could someday turn on my cellphone and listen to my conversations, she said.

Nathan F. Wessler for petitioner (Art Lien)

Sotomayor saw no reason why the court shouldn’t carve out an exception to the third-party doctrine to resolve Carpenter’s case. The doctrine, she noted, was never an absolute rule – for example, the Supreme Court has ruled that police can’t obtain medical records without the patient’s consent, even when the hospital (rather than the patient) is holding the records. Is it really that far off, she asked, to say that even if someone’s location at a specific place at a specific time might not be private, anyone would have an expectation of privacy in their whereabouts over 127 days?

Breyer echoed this idea. He agreed with Dreeben that, as a general rule, information shared with a third party would not be shielded from disclosure, but he proposed an exception to that rule to account for the significant changes in technology. Breyer returned to this idea later, telling Dreeben that the cellphone records at issue in this case are “highly personal,” more like medical test results than the kind of commercial information that has been disclosed under the third-party doctrine.

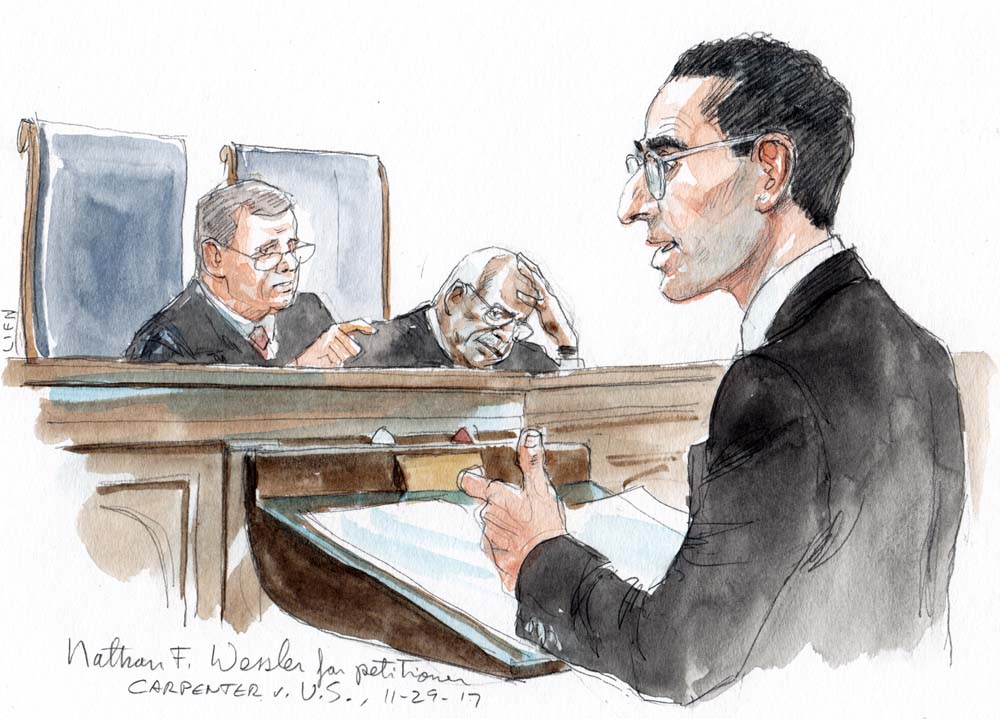

Justice Samuel Alito agreed that new technology has raised new concerns, but he appeared less receptive to the idea of carving out an exception to the third-party doctrine. He asked Wessler how he would distinguish the court’s earlier cases on the third-party doctrine. And in particular, he asked, is it really true that cell-site data are more sensitive than bank records? These days, Alito pointed out, because people rarely pay in cash, bank records can disclose everything – from magazine subscriptions to hotel stays – that someone purchases.

Wessler responded that most people know that their purchases can be revealed to others, but they have an expectation that their long-term movements will remain private. He suggested that the court could draw a temporal distinction, which would allow police to look at cell-site data for shorter periods of time – say, 24 hours – but not for 127 days, as in this case.

For Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, that line didn’t seem to make sense. Why, she asked, can police get cell-site data for the day of one robbery, but not for the other seven? Why wouldn’t it be reasonable to get that data for each day?

Kennedy was even more dubious. He told Wessler that allowing police to obtain cellphone records over a longer period of time could actually help a suspect to demonstrate his innocence – for example, by showing that he was normally in a particular area every day, not just on the day of a crime.

Breyer, who is famous for his long and sometimes rambling hypotheticals, summarized the dilemma facing the justices succinctly: “How do we draw the line?” Dreeben gave a quick response, telling the justices that he didn’t “think it can be drawn coherently.” But despite Dreeben’s pessimism, the justices seem likely to try. Their answer may not ultimately help Timothy Carpenter — Alito pointed out today that, under the Supreme Court’s caselaw, evidence from a search does not have to be excluded when the search was conducted pursuant to a statute that is later deemed unconstitutional – but it will nonetheless be a significant one for privacy law.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.