Empirical SCOTUS: Something we haven’t seen in the Supreme Court since the Civil War

on Apr 16, 2020 at 5:22 pm

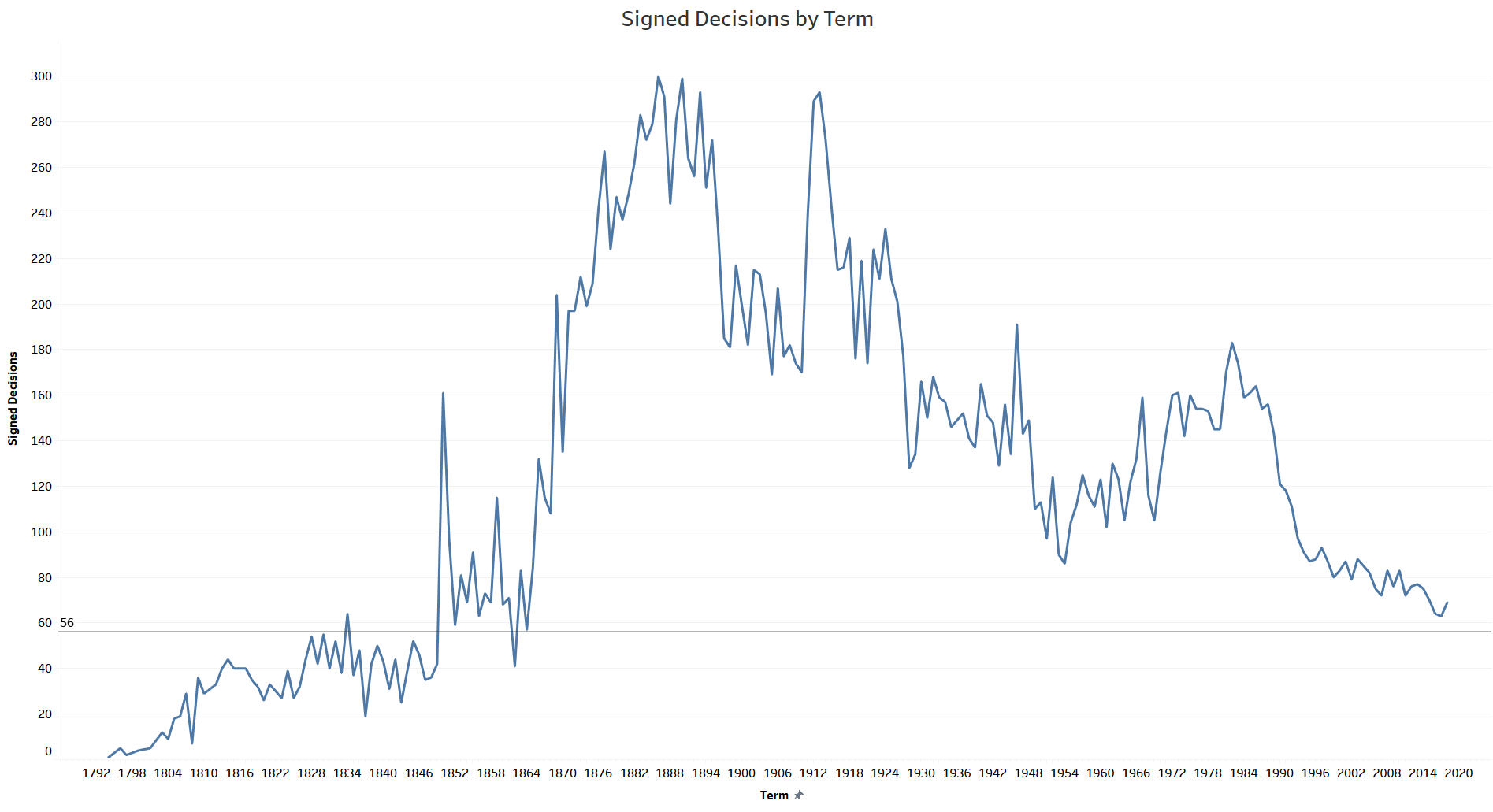

The Civil War was fought between 1861 and 1865, and the Supreme Court was affected by the war like all national institutions. During the second year of the war in 1862, the court decided 41 cases by signed decisions, and in 1864 the court decided 57 such cases. According to the U.S. Supreme Court Database, these were the fewest decisions the court had rendered in any year since 1849. If the Supreme Court decides all the cases already argued this term along with the additional cases slated for argument in May by signed decisions, the number of decisions for OT 2019 will reach 56. Even with several recent terms in which the justices’ opinion output dipped to historic lows, 56 signed decisions would be the fewest since 1862, and, aside from the blip due to the Civil War, the fewest since 1849.

Unlike recent terms, in which most cases have come from the federal courts of appeals, the bulk of cases in the 1860s came from a smattering of federal courts, ranging from the Wisconsin and California Northern U.S. District Courts to the U.S. Circuit Courts for Illinois and New York (federal appellate courts that existed prior to the current system of 12 circuits). While almost all cases currently arrive at the Supreme Court through petitions for writs of certiorari, a discretionary mechanism of appeal, all cases in 1862 were appealed by writs of error or mandamus, direct appeals, or through certified questions to the court. Suffice it to say the court functioned very differently in 1860s than it does today.

This term the court has decided 19 cases by signed opinions so far. Justice Samuel Alito has the most majority opinions, with four, followed by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, with three. Chief Justice John Roberts is the only justice who has yet to author a majority opinion.

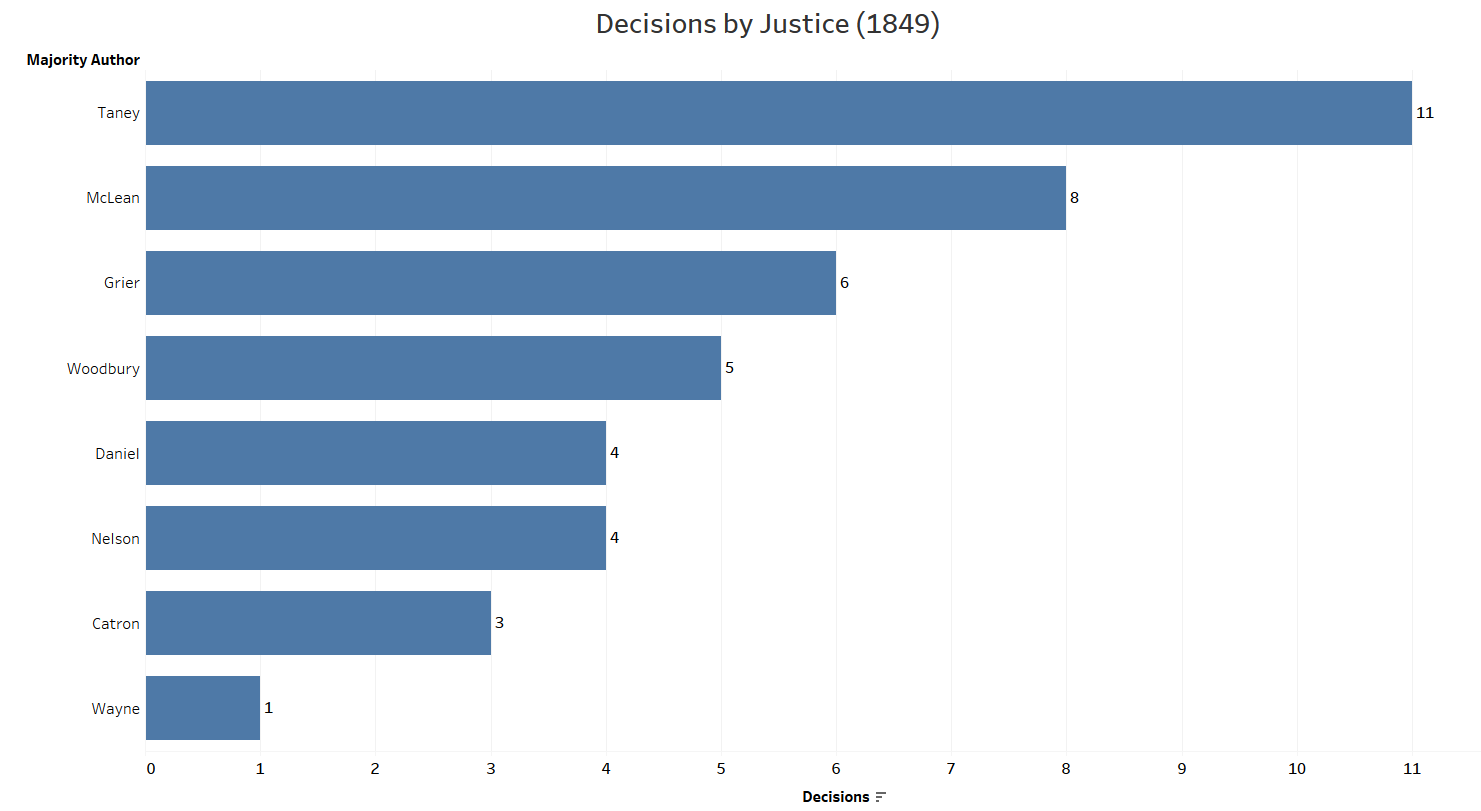

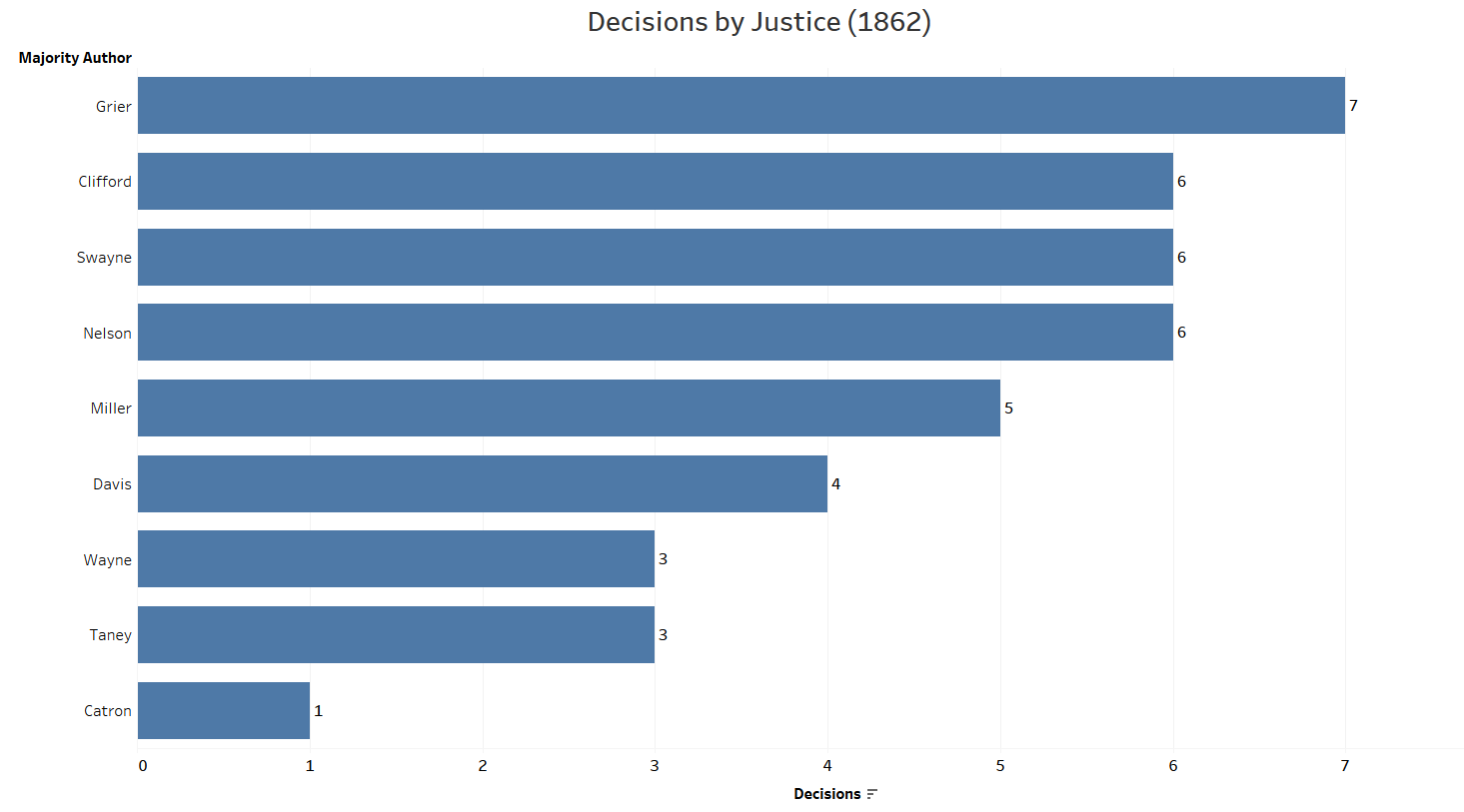

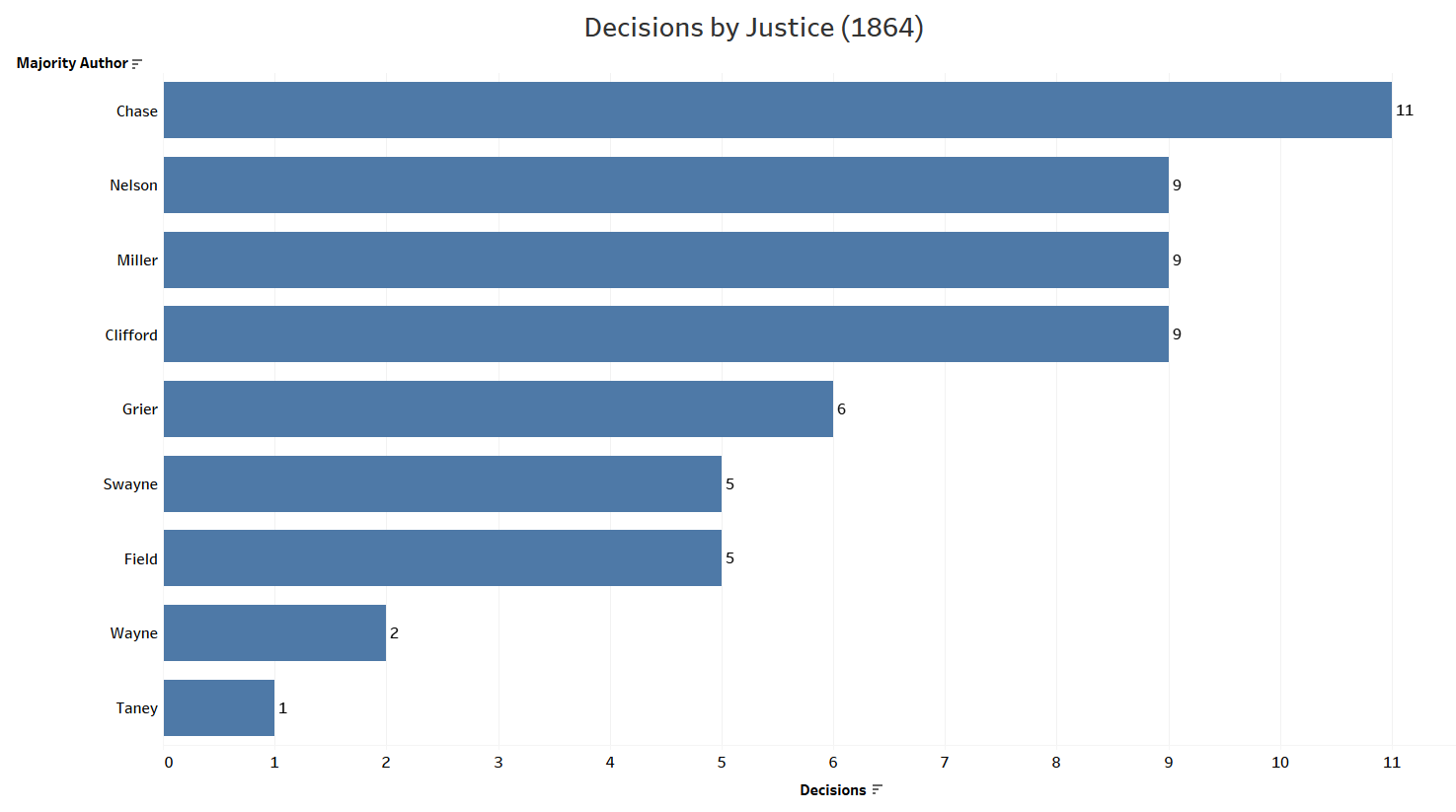

The chief justice from 1832 to 1864 (thus for two of the terms under inspection, 1849 and 1862) was Roger Taney, who in 1857 authored the infamous majority decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford. Taney died in 1864, and Salmon Chase was then appointed chief justice.

In 1849 Taney authored the most majority opinions of the justices.

In 1862, two years before his death, Taney authored the second fewest majority opinions of the justices.

Including Taney, five justices sat on the court both in 1849 and in 1862. The new chief justice in 1864, Chase, authored the most majority opinions of the justices that term.

Unlike current terms, in which majority opinions are generally dispersed evenly among the justices, opinion assignment in the mid-1800s was skewed, so that some justices authored the bulk of opinions, leaving others with very few authorship opportunities.

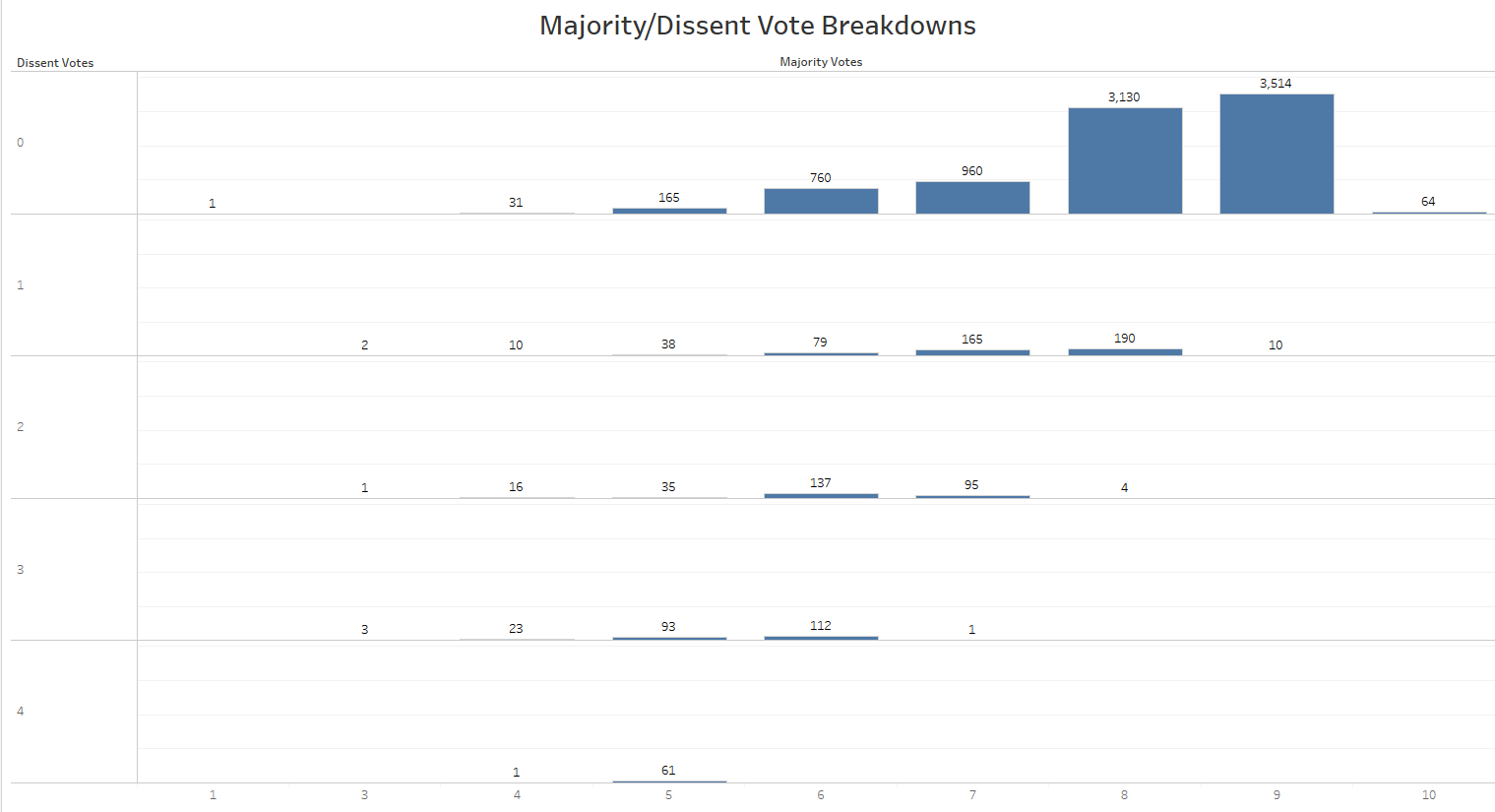

So far this term three cases were decided 5-4, which amounts to 16 percent of the signed decisions. Nine cases so far, or 47 percent of the signed decisions this term, had at least one dissent. Although the small sample size of opinions this term makes it difficult to draw comparisons across entire terms, this marks a significant change from Supreme Court decision-making historically. In 1862, at least one justice dissented in five decisions, or 12 percent of the court’s cases, and only one case had four dissenting votes. In 1864, five decisions included dissents, amounting to 9 percent of the decisions for the term, and none included four dissenting votes. The historic frequency of unanimity is made clearer by the following chart depicting vote breakdowns for all the court’s signed decisions between 1794 and 1894.

As is evident from the chart, the disparity between decisions with unanimous votes and those with four dissents shows that the justices were much more averse to dissenting in the court’s first 100 years or so.

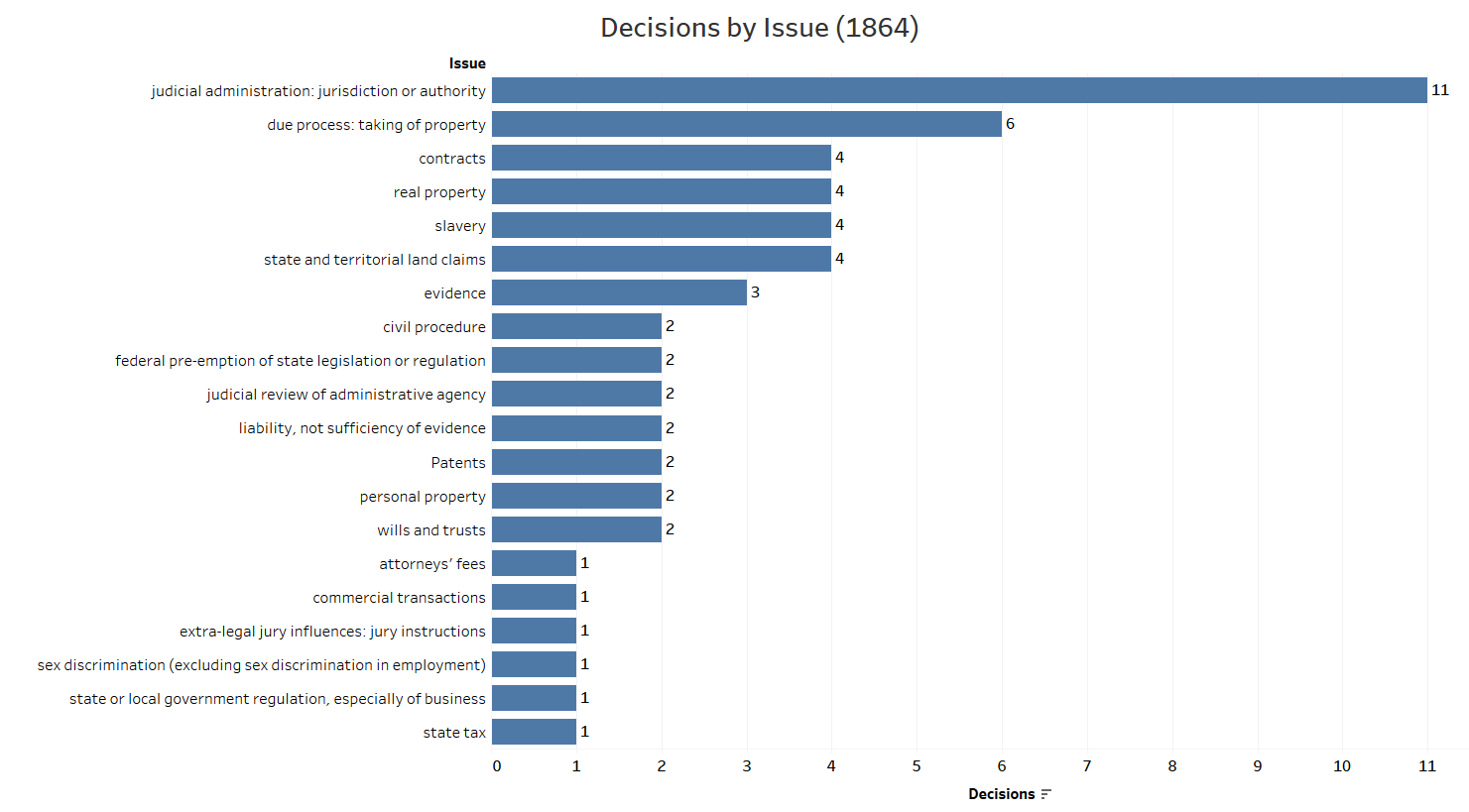

This term the court heard a mix of cases dealing with issues ranging from discrimination based on sexual orientation or transgender status, to gun rights, to an upcoming argument over the release of President Donald Trump’s financial records. Not surprisingly, the issues the court faced in the mid-1800s were much different, though there are some similarities.

Looking at the 1864 term, for example, the court decided more cases dealing with jurisdictional issues, related to when the court had the ability to hear a case, than any other case type.

As in the current term, the court in 1864 also heard a case dealing with a discrimination claim. In that case, Drury v. Foster, the court examined a wife’s right to mortgage property separately from her husband and the right of a mortgagee to foreclose on that property — quite a different type of discrimination action from the cases argued in OT 2019.

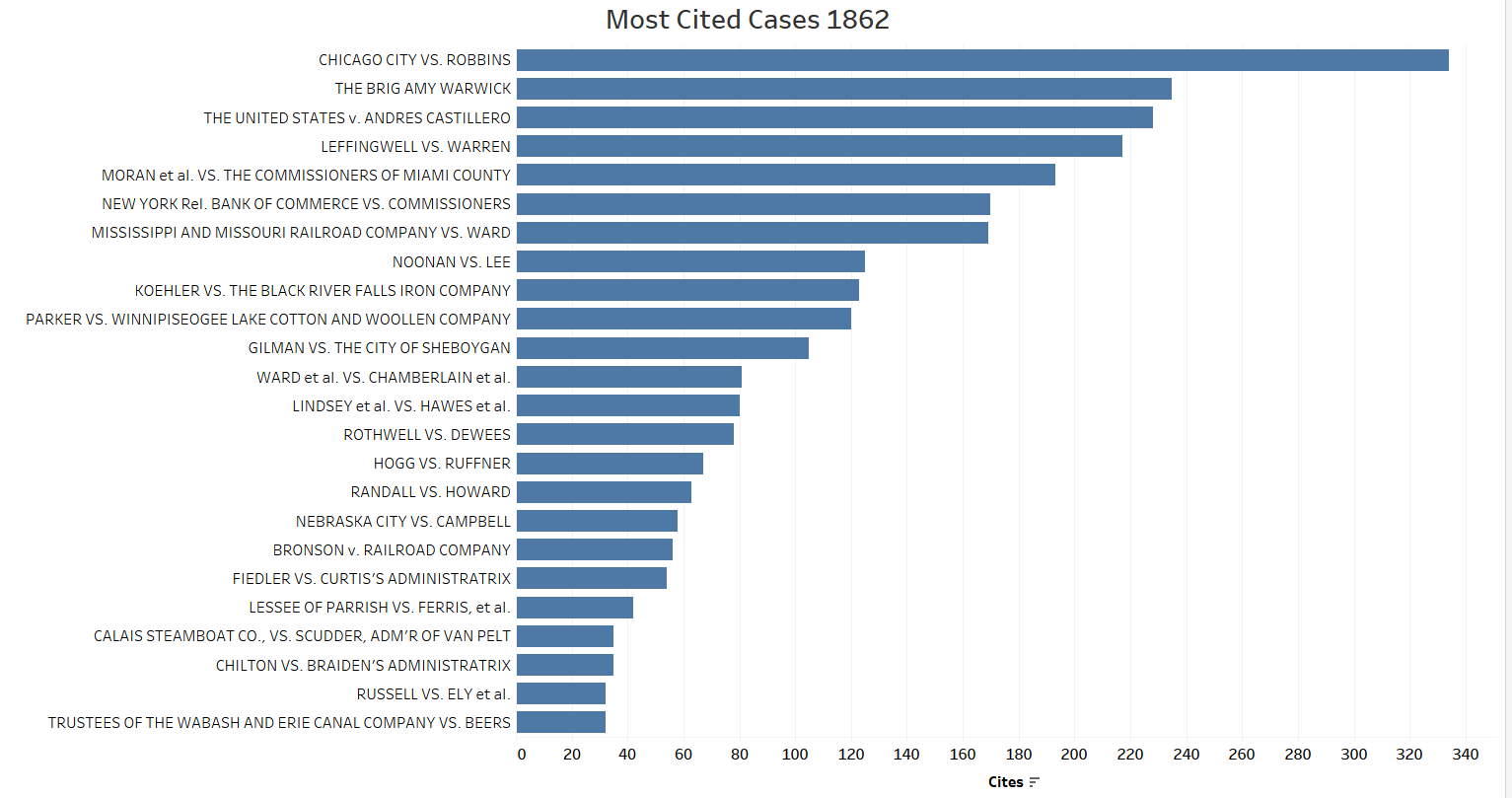

Another way to examine the cases in these terms is by citation counts. In 1862, the case with the most subsequent citations, Chicago City v. Robbins, has been cited in 334 combined state and federal court opinions. The figure below shows all decisions from the 1862 term cited in at least 30 court opinions.

This chart gives a sense of the relative jurisprudential importance of the cases from the 1862 term. Robbins is a tort case, in which the justices determined whether the city or a private owner was negligent in a dispute over the injury of a third party who fell through an excavated portion of the sidewalk.

The differences between the modern court and the court in the 1860s, the last time it decided as few or fewer cases than it will this term, are readily apparent. Since 1849, however, what is similar between the low output this term and in the 1860s is the ability of an issue of grave national importance, the Civil War in the 1860s and COVID-19 currently, to force such case curtailments.

This post was originally published at Empirical SCOTUS.