Argument analysis: Justices grapple with preclusion and “occupation” in Crow Tribe treaty case

on Jan 9, 2019 at 10:42 am

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court heard argument in its latest foray into Indian treaty interpretation, Herrera v. Wyoming. The case concerns the persistence of the Crow Tribe’s hunting right in the 1868 Second Treaty of Fort Laramie. In an occasionally meandering argument, the Supreme Court repeatedly circled the three issues at the core of the case: issue preclusion, the implications of the court’s holding in its 1999 decision in Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, and the meaning of the treaty term “unoccupied.”

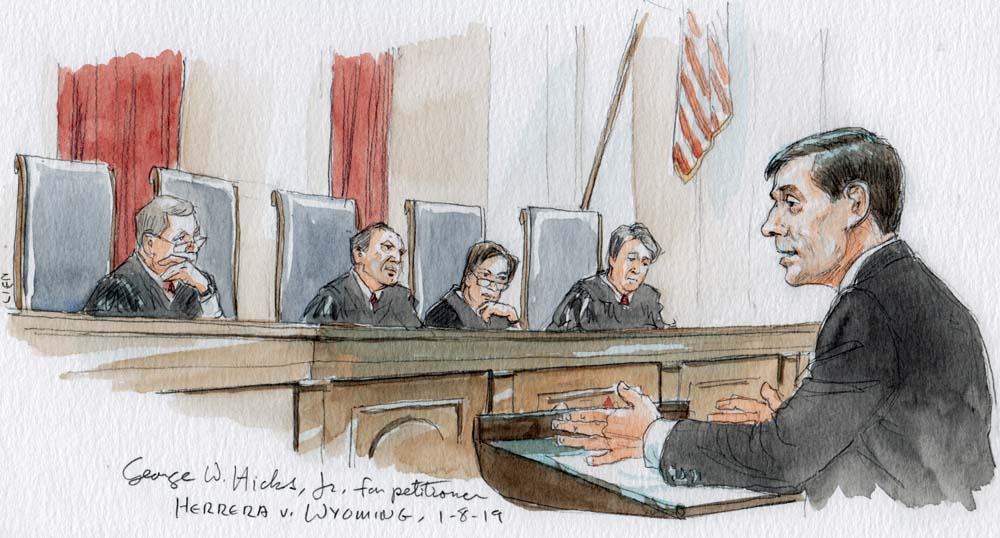

The argument began with George Hicks, counsel for the petitioner, Clayvin Herrera, confronting questions about why the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit’s 1995 decision Crow Tribe v. Repsis, which found that the Crow’s treaty right had been abrogated, did not bar Herrera from relitigating the treaty issue. In a discussion that Justice Samuel Alito likened to law school, the justices pressed Hicks on the effect for future litigation of decisions like Repsis that reached multiple, alternative holdings. But when John Knepper, counsel for Wyoming, rose, the justices had pointed questions on this topic for him, too, particularly about his insistence that Mille Lacs (which undermined the doctrinal foundation for Repsis) was not a significant enough change in the legal context to warrant an exception to the normal preclusion rules. When asked what the test for such a change would be, Knepper offered up a “a major doctrinal shift.”

In fact, much of the argument focused on the puzzle of what, exactly, the Supreme Court had done in Mille Lacs, and how large a shift the case represented. In the 1999 decision, the court effectively repudiated a century-old ruling called Ward v. Race Horse that statehood could abrogate Indian treaty rights, yet the court stopped short of explicitly overruling Race Horse. Justice Brett Kavanaugh pushed Hicks, Herrera’s attorney, on the seeming anomaly that this situation might create. The Crow treaty contained the “exact same treaty language” as the Shoshone-Bannock treaty at issue in Race Horse, but, if the Supreme Court found for Herrera, the Crow would enjoy their treaty right while the Shoshone-Bannock would still be bound by Race Horse. Hicks pointed to historical distinctions between the situation of the two tribes. Confronted with the same question, Frederick Liu, arguing for the federal government in support of Herrera, invited the court to expressly overrule Race Horse.

Yet Knepper, arguing for Wyoming, also faced tough questions about his claims that anything from Race Horse survived Mille Lacs. As Justice Stephen Breyer outlined, Mille Lacs had rejected every rationale from Race Horse. As for why the court did not just overrule Race Horse, Breyer pointed out that there were compelling practical reasons that “I can understand” as to why the justices might have declined to explicitly overrule a prior case even when they were effectively doing so.

Finally, many of the justices’ questions related to whether the Bighorn National Forest, where the disputed elk killing occurred, constituted “unoccupied” federal lands on which the Crow treaty guaranteed hunting rights. When Liu for the federal government argued that it did, Chief Justice John Roberts suggested that Liu was ”walking a really thin tightrope” because he was arguing simultaneously that the mere proclamation of a national forest did not render the land “occupied” but that the federal government could, in certain instances, administer forest lands in ways that would make them “occupied.” Liu posited as the relevant test whether the land was settled, and pointed to federal regulations barring firing a gun within 150 yards of an occupied area as a sensible line. Arguing for Wyoming, Knepper offered a more intricate test, drawing on history to posit that “occupied” was a “term of art” that encompassed only “lands of such a character as would be embodied in hunting districts.” The justices were skeptical of Knepper’s claim. Roberts characterized it as a “bit of a stretch”: “[Y]our argument is … what did they mean by ‘cow’ and you’re saying they meant ‘horse.’”

Ultimately, Herrera will likely yield a narrow decision that breaks little new doctrinal ground. The Supreme Court may clarify, or even formally overrule, Race Horse, and may also construe the treaty term “occupied.” But the justices seemed to have little appetite to resolve uncertain issues about the federal law of preclusion, with several suggesting that those be left for state courts on remand.

But there were also moments when the justices addressed the broader issues at stake, particularly when they discussed Wyoming’s ability to regulate the Crow treaty right for conservation reasons. Knepper for the state suggested that the doctrine of conservation necessity, under which states can regulate Indian treaty hunting and fishing to conserve natural resources, would only partially vindicate Wyoming’s concerns, because it might not encompass safety or disease measures (although several justices seemed to think that existing doctrine could, in fact, vindicate these interests). Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out that there were interests on the other side, too: The Crow had ceded millions of acres of land in return for the promised preservation of an economically and culturally central right. “The balance is not yours alone to make,” Sotomayor suggested to Knepper. “It belongs to the [federal] government and it belongs to the Indian tribes as well.” This colloquy served as an important reminder of the significant stakes for Wyoming, the Crow Tribe and Clayvin Herrera in what lawyers might deem a doctrinally narrow case.

Editor’s Note: Analysis based on transcript of oral argument.