Empirical SCOTUS: Getting rid of those amicus blues

on Jul 16, 2018 at 2:16 pm

Good writing makes a world of difference in appellate practice. In an era when some scholars question whether oral arguments have very much utility, briefs, and especially amicus briefs, are thought to play a unique role in Supreme Court decision-making. The court receives briefs in large numbers, with amicus briefs leading the way. Cases with broad national repercussions may garner 100 amicus briefs or more (one example of a case with over 100 such briefs is Obergefell v. Hodges). With so many filings, the justices tend not to read each brief and may instead delegate the bulk of this task to their clerks.

Groups filing amicus briefs have several ways to capture the attention of clerks and justices. Certain groups with already established credibility like the Office of the Solicitor General are known to have an impact on the court’s opinions through their amicus briefs. Others that lack this institutional standing must seek out alternative means to persuade justices and clerks to read their writings.

Studies suggest that aspects of brief-writing can positively affect the evaluation of briefs. Even though there are several off-the-shelf metrics for writing quality, few if any have been successfully employed by a large number of legal writers.

Recently, software has started to fill in this gap with multi-dimensional writing-analysis tools. One tool that has received praise from several industry analysts is BriefCatch (Empirical SCOTUS also recently used BriefCatch to evaluate Supreme Court cert stage filings, and evidence suggests that BriefCatch’s popularity is beginning to permeate through legal practices.).

The sample for this post is the over 800 amicus briefs filed in the Supreme Court on the merits for the 2017 term. BriefCatch was run on plain-text versions of each brief in the dataset. BriefCatch provides five quantitative measures of writing quality. To collapse these measures, this post uses the average (mean) as the focal variable.

BriefCatch’s scores run from zero to 100 for the five measures, which are Flow, Plain English, Punchiness, Reading Happiness and Sentence Length. To get a sense of how briefs performed on these individual measures, the first figure shows box-plot distributions for each score. Box plots show the median score (the middle of the box) along with the distribution of scores around the median. Each dot reflects an individual brief’s score.

From this we see that brief authors tended to score higher on some scores like punchiness than they did on other scores like sentence length. (If you have ever read a legal brief you probably understand why.) When these scores are combined into one average score per brief, a separate distribution is created that is displayed in the following figure.

This shows that most of the briefs’ average scores were between 78 and 80, but that some scores were in the low 50’s and others were in the high 90’s.

These composite BriefCatch scores were then used to make comparisons between briefs and between groups of briefs. To start we can look at the scores on a case-by-case basis. The following shows the number of amicus briefs evaluated for each case this term and the average composite scores across all briefs by case.

Many of the highest average brief scores are based on only a few briefs. Briefs filed in Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky have the highest average composite score in a case with 10 or more briefs. The case with the most briefs for this past term, Masterpiece Cakeshop, ranks in the top half for average brief score.

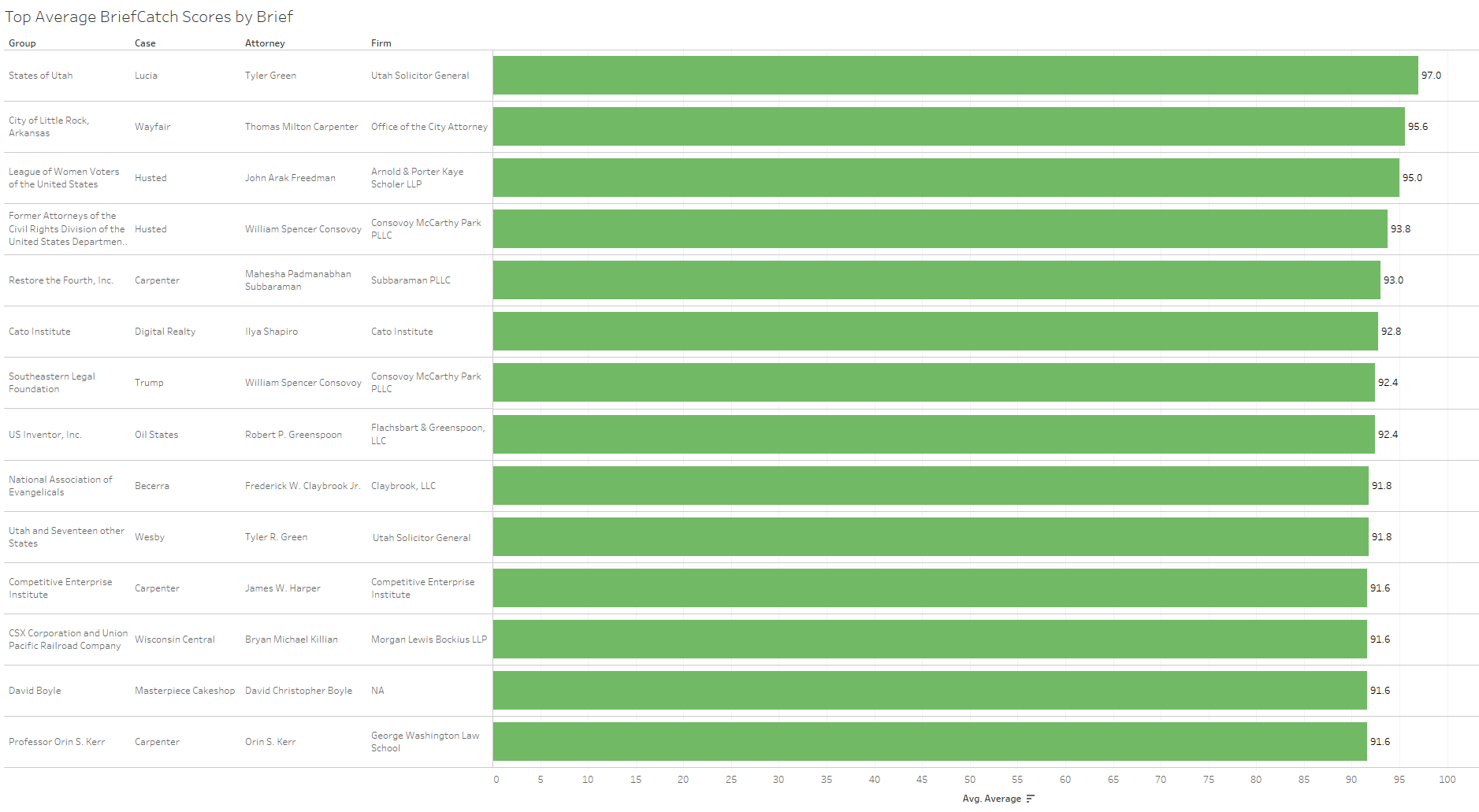

Next, these average scores by case are disaggregated into individual briefs’ scores. The following figure shows the top-ranked briefs from the term. All of these briefs had average scores greater than 91.5 and, referring back to the previous figure, fall to the right edge of the distribution.

The top-scoring brief was from Utah’s Solicitor General Tyler Green in Lucia v. SEC. Another one of Green’s briefs, the one from D.C. v. Wesby, ranked in this top group as well. The second-ranked brief in the set was also from a state or local level attorney, Thomas Carpenter from the Office of the City Attorney in Little Rock, Ark., in the Wayfair case. The third-ranked brief was the top brief authored by an attorney in a private law firm. The counsel of record for this brief, filed in the Husted case on behalf of the League of Women Voters, was Arnold & Porter’s John Freedman.

Consovoy and McCarthy’s William Consovoy is the other attorney, along with Tyler Green, with more than one brief in this figure. Consovoy’s briefs were on behalf of Former Attorneys and the Southeastern Legal Foundation in the Husted and Trump v. Hawaii cases respectively.

The figure for top-scoring average attorney with multiple amicus briefs for the term correlates strongly with the top briefs figure: Several attorneys are present in both, including Tyler Green.

The second- and third-ranking attorneys on this list, Mahesha Subbaraman and Frederick Claybrook, also have briefs that made the top briefs chart, while the fourth listed attorney, David A. French, did not. Among the attorneys on this list are two of the most prolific Supreme Court attorneys presently in practice, Carter Phillips and Charles Rothfeld.

Along similar lines, the law firms of record on the briefs come primarily from the top-ranked amicus attorneys in this post. The firms of record can be distinguished from filing groups, as they are on the Supreme Court docket. The example below shows an entry from the court’s docket in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case.

To the right of the attorney is the attorney’s law firm or place of practice, Mauck & Baker in this instance, and below is the name of the group on whose behalf the brief was filed, here C 12 Group, et al. The docket usually contains the name of the first listed firm and group and tends not to include multiple entities even if they appear on the brief itself.

The two top-ranked repeat player amicus firms for the 2018 term, Subbaraman PLLC and Claybrook, LLC both include top-scoring attorneys: Mahesha Subbaraman and Frederick Claybrook. Other firms that ranked in this top tier include the National Review Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute and First Liberty Institute. UCLA School of Law’s Supreme Court Clinic was the top-ranked law school clinic. The Cato Institute was the most active amicus filer in this top tier, as it often files as many or more briefs than any other amicus producer for the Supreme Court on an annual basis. Nine of the Cato Institute’s briefs were evaluated for this post.

The United States regularly is the most active amicus filer before the Supreme Court. This post evaluated 19 amicus briefs filed by the United States on the merits. The next figure compares the United States’ composite brief scores by case.

The United States had one amicus brief this term with a composite score of over 90. This was in Murphy v. NCAA. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the United States’ lowest scoring brief was in the Wayfair case.

The final figure in the post looks at the top five amicus groups by average composite score. The group is the “party name” on the docket sheet. which comes below the name of the amicus attorney and is the entity on behalf of whom the brief is filed.

The Cato Institute, which was one of the top-ranked amicus firms, was the top-ranked group overall for the term. The second-best-faring group was the Pacific Legal Foundation, followed by the Institute for Justice, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and the ACLU. The range for all five of these groups’ composite scores is less than five points, indicating that the scores at the top are tightly packed compared to the range of scores conveyed by the total distribution.

The number of amicus briefs filed each term far outweighs the number of briefs filed by direct parties. These amicus groups vie against one another for the court’s attention, because the resources for evaluating these briefs are limited. High-quality writing remains one of the best ways for groups to get the court’s attention, especially when the group does not have the institutional presence of the United States.