Academic highlight: Hinkle and Nelson look at why some dissents become doctrine

on May 4, 2018 at 5:06 pm

Some of the more memorable phrases from the Supreme Court’s history come from dissents, not the court’s majority opinions. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s analogy in her dissent in Shelby County v. Holder – that invalidating a section of the Voting Rights Act is “like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet” – made its way into a new documentary about the justice and arguably contributed to her rise to social media stardom.

Two political scientists, Rachael Hinkle and Michael Nelson, take a look at the memorable language in this dissent and others in a forthcoming article, “How to Lose Cases and Influence People.” As Hinkle and Nelson note, “anecdotal evidence of change in doctrine fueled by a past dissent abounds.” At the same time, there’s little in the way of empirical scholarship as to why some dissents eventually change doctrine, and others don’t. According to Hinkle and Nelson, theirs is “the first large-scale empirical examination of the legal influence of dissenting opinions in the US Supreme Court.”

The authors focus their analysis on “the language used to craft” dissents, which they consider the “one key factor … squarely in [a justice’s] hands – how much effort they devote to making their words memorable.” “The sine qua non of influence is recall,” Hinkle and Nelson suggest, because “a dissent that is forgotten cannot be expected to influence legal development.” Starting from a dataset of 5,795 dissenting opinions written from 1937 to 2014, the authors identify 923 dissents that “received a non-negative citation from at least one subsequent majority opinion.”

According to the authors, existing research in political and computer science has determined that two types of language are particularly memorable – emotional language and distinctive language.

Borrowing from linguistic tools and approaches, Hinkle and Nelson use the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count software to calculate “word counts for a number of psychologically significant categories of vocabulary including words that indicate both positive and negative emotion.” This approach requires some modification because some words, like “complaint,” do not carry the same emotional weight in the legal context as in common English usage.

Hinkle and Nelson define as distinctive “any word that is in the bottom ten percent of the relevant frequency distribution.” Both “umbrella” and “rainstorm,” from Ginsburg’s Shelby County dissent, are classified as distinctive by this measure. As an example of the divergence between legal English and everyday English, the authors note that the words “omnibus” and “butt” have each been used an identical 250 times in Supreme Court majority opinions through the October 2015 term. In general usage, “these two words are clearly not used with similar frequency,” the authors write, just as “umbrella” and “rainstorm” might not seem like distinctive words outside the Supreme Court.

The authors find support for two hypotheses. First, their research shows that increases in the amount of emotional language are positively associated with a dissent’s effect on legal development. However, this effect only applies to negative emotional words; “positive emotion words do not have a statistically significant impact.” Although they had not originally expected this result, it does accord with existing research showing that “negative emotion is more easily recalled than positive emotion.”

Second, Hinkle and Nelson’s research shows that increases in the amount of distinctive language are also positively associated with a dissent’s influence on future cases.

Abortion caselaw provides an example of this phenomenon. As Hinkle and Nelson explain, the Supreme Court in the 1992 case Planned Parenthood v. Casey applied an undue burden test to abortion restrictions, a significant shift from the strict scrutiny test applied in the 1973 case Roe v. Wade. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor first suggested this change in legal doctrine in her 1983 dissenting opinion in City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health. O’Connor’s City of Akron dissent used 55 negative emotional words and 126 distinctive words, well above the averages in those categories across all dissents of 27 and 31, respectively. Although many factors contribute to the development of legal doctrine, O’Connor’s use of negative-emotion words and distinctive words likely made her dissent “stand out and, therefore, have a greater effect on the development of the law.”

Hinkle and Nelson also address a third possible explanation for a dissent’s future impact – the strength of the dissenter’s views on the matter. To address this possibility, the authors contrast dissents concluding with “I respectfully dissent” with those simply saying, “I dissent.” The “seemingly innocuous” latter phrase “is rendered vituperative,” the authors explain, because of a norm established under Chief Justice Earl Warren of justices explicitly stating their respect for their colleagues. In accordance with this norm, only six percent of the dissents in the first five terms of the Roberts court included the blunter ending. Nevertheless, although the authors caution against “interpreting a null result with meaning,” they find no statistically significant relationship between this variable and the likelihood of a dissent’s future citation in later terms.

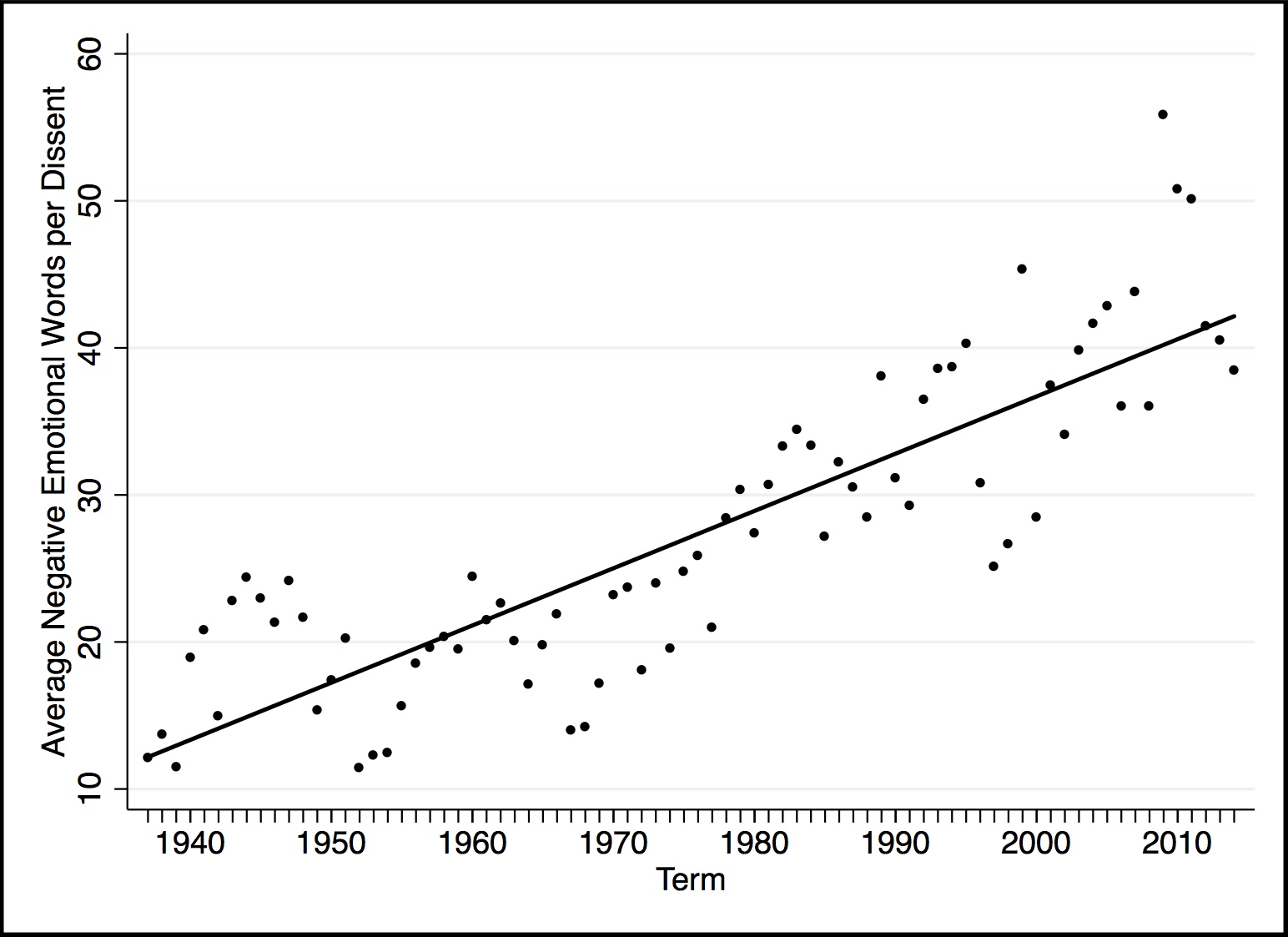

Hinkle and Nelson’s data concerning the average number of negative words justices use in dissenting opinions reveal an interesting trend. In looking through their tables, I noticed that out of 37 justices who joined the court in 1937 or later, the 10 justices with the highest average number of negative words per dissent written through 2014 all joined the bench after 1981. Ginsburg, the one justice to join the bench since 1981 who is not part of the top 10, comes in at 16. (Justice Neil Gorsuch is not included because he joined the bench after 2014.) After I pointed this out, Hinkle produced the graph below, which shows a consistent increase in the average number of negative emotional words.

Hinkle, who has not been able to do extensive analysis on this new graph, told me that this increase in the usage of negative emotional words over time “is a bit of a puzzle.” One possibility might be that the total number of separate opinions is increasing over time. As a result, “justices may feel an increasing need to make their dissents stand out.” It’s also “conceivable that justices have long realized that negative emotional language is a way to catch attention and that the observed pattern is the result of a sort of ‘arms race’ in which justices realize they have to keep using more and more negative emotional language in order to garner readers’ attention.”