A “view” from the courtroom: An audience of luminaries for the final argument of the term

on Apr 25, 2018 at 3:26 pm

It’s a warm but drizzly day in Washington as people line up for the last argument of October Term 2017. Some have spent a night or two in the public line, while the well-connected have tickets. Today, the latter will include one star of the Broadway stage, a few members of Congress and at least one senior White House official.

The first familiar face we spot in the courtroom today is Scott Keller, the Texas solicitor general, who argued his state’s redistricting case yesterday and is the counsel of record on the amicus brief of Texas and 14 other states (or their governors) in support of President Donald Trump’s proclamation restricting travel to the United States by nationals of certain countries.

The case, Trump v. Hawaii, is the only one for argument today.

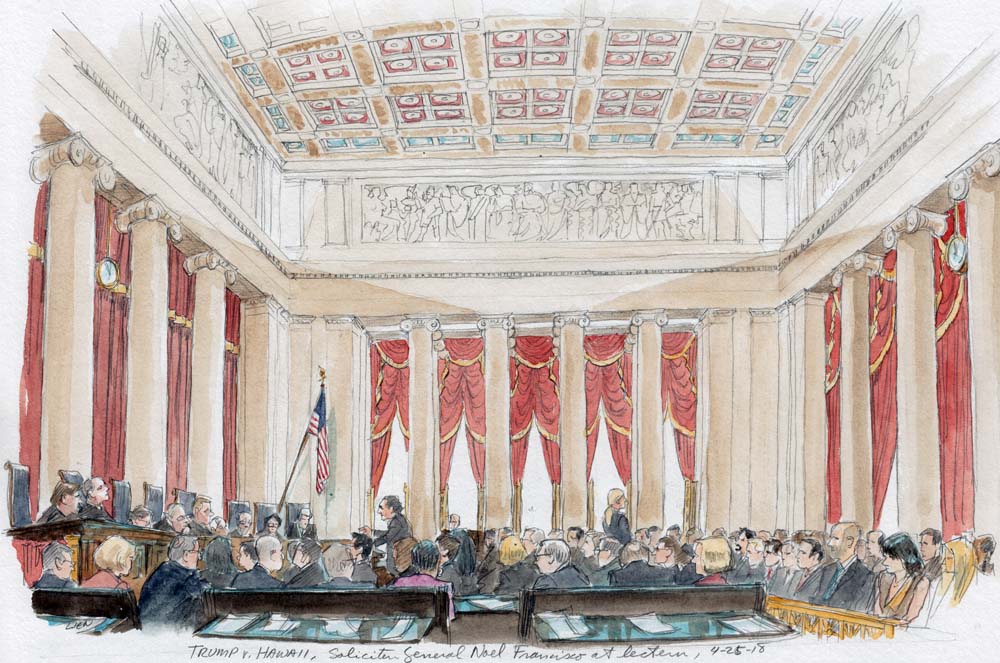

Wide-shot of courtroom during travel ban argument, Solicitor General Noel Francisco at lectern (Art Lien)

Sen. Mazie Hirono, Democrat of Hawaii, arrives and takes a seat in the front row of the public gallery. She is one of 31 senators and dozens of House members who have signed an amicus brief supporting Hawaii’s challenge to the president’s proclamation.

Sen. Orrin Hatch, Republican of Utah, who has not signed on to that brief, arrives and takes a seat in the bar section. But he soon stands up to gladhand a bit and chat with another bar member.

At 9:35 a.m., the courtroom receives a touch of true celebrity and talent when Lin-Manuel Miranda, the author (and original player of the title role) of the Broadway hit “Hamilton” arrives, accompanied by his wife, Vanessa Nadal, a lawyer and scientist. They are seated in the third row of the public gallery. Later, Josh Blackman, a professor at South Texas College of Law in Houston and frequent observer of the court, will tweet a picture of the Miranda autograph he got before the argument on his pocket copy of the U.S. Constitution, a version published by the libertarian Cato Institute. (Miranda will also take to Twitter, writing, “I was @VAMNit’s +1. Honored to be in the room where it happened today. Proud of our friend @neal_katyal.”)

The VIP section has some familiar faces today. We spot four spouses of the justices — Mary Kennedy, Joanna Breyer, Martha-Ann Alito and Louise Gorsuch. Absent are Virginia Thomas and Jane Roberts, who accompanied her husband, Chief Justice John Roberts, to the state dinner at the White House last night in honor of President of France Emmanuel Macron.

Also in the VIP section is Harvard Law School professor Richard Lazarus, a close friend of the chief justice. And three staff members and court aficionados from the Heritage Foundation also get prime seats — John Malcolm, Hans von Spakovsky and Tiffany Bates (the co-host of the foundation’s “Scotus 101” podcast).

White House Counsel Don McGahn arrives and is seated in the second row of the public gallery. A few minutes later, Cecelia Marshall, the widow of the late Justice Thurgood Marshall, arrives with a small group of friends and is seated by the court’s staff right next to McGahn. Neither seems to recognize each other. They will observe the argument from virtually the same view, but likely very different perspectives.

When the justices take the bench, Roberts recognizes Hatch to perform the function of introducing several lawyers to be admitted to the Supreme Court bar and to vouch for their qualifications. No one seems upset when Hatch departs from the script slightly to say to the justices, “I’m glad to see all of you this morning.”

After just a couple more bar admissions, and mercifully no large groups of lawyers being inducted as there are on most court days, Roberts calls the entry-ban case. (Hatch is evidently not interested enough in the case to stick around, and he slips out at the end of the bar-induction ceremony.)

What follows is a fast-moving, hard-hitting hour (slightly more, actually) that more than lives up to its billing as a fitting finale for arguments this term. Amy Howe has this blog’s main account of the back and forth.

U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco argues passionately for the legality and constitutionality of the third iteration of Trump’s entry ban, this one barring immigration from six majority-Muslim countries: Chad, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. (Chad has since been dropped from the list.)

“This is not a so-called Muslim ban,” Francisco says. “If it were, it would be the most ineffective Muslim ban that one could possibly imagine since not only does it exclude the vast majority of the Muslim world, it also omits three Muslim-majority countries that were covered by past orders, including Iraq, Chad, and Sudan.”

Justice Elena Kagan presses him with a hypothetical involving a president “who is a vehement anti-Semite and says all kinds of denigrating comments about Jews and provokes a lot of resentment and hatred over the course of a campaign and in his presidency” before ending up with “a proclamation that says no one shall enter from Israel.”

“This is an out-of-the-box president in my hypothetical,” Kagan says, to laughter in the courtroom.

Francisco responds that it is a “very tough hypothetical,” but “if his cabinet were to actually come to him and say, Mr. President, there is honestly a national security risk here and you have to act, I think then that the president would be allowed to follow that advice even if in his private heart of hearts he also harbored animus.”

Neal Katyal, representing Hawaii and other respondents who have challenged the president’s orders, tells the justices that “if you accept this order, you’re giving the president a power no president in 100 years has exercised, an executive proclamation that countermands Congress’s policy judgments.”

Katyal receives considerable pushback. Justice Samuel Alito tells him that “if you look at what was done, it does not look at all like a Muslim ban. There are other justifications that jump out as to why these particular countries were put on the list.”

When Roberts presses Katyal about how much authority the president has to act in a national security emergency, Katyal says the president would have broad authority.

“But here we are 460 days later, Mr. Chief Justice,” Katyal says. “He’s never even introduced legislation about this.”

“Well,” the chief justice replies, “Imagine, if you can, that Congress is unable to act when the president asked for legislation.” This evokes knowing laughter in the courtroom.

Later, Katyal is able to sum up his central argument.

“Our fundamental point to you,” he says, “is that Congress is in the driver’s seat when it comes to immigration, and that this executive order transgresses the limits that every president has done with this proclamation power since 1918. And to accept it here is to accept that the president can take an iron wrecking ball to the statute and pick and choose things that he doesn’t want for purposes of our immigration code. That can’t be the law of the United States.”

The chief justice, who had indicated that Francisco would be given some time for rebuttal because the last few minutes of the solicitor general’s argument had been eaten up by questions, does the fair thing, as he usually does, and also offers extra time to the respondent.

“Take five extra minutes,” Roberts says to Katyal.

But Katyal, who has argued this case several times in the court below and had seemed satisfied with his closing, is slightly thrown by this offer.

“Okay, okay,” he says, mulling what he might add. The chief justice says, “You don’t have to.”

So, with no further questions from the bench, Katyal declines the extra time.

Francisco returns to the lectern for his rebuttal. After answering a few questions, he seeks to make his conclusion, which ends up coming out a little bit jumbled.

“The president has made crystal clear on September 25th that he had no intention of imposing the Muslim ban,” Francisco says. “He has made crystal clear that Muslims in this country are great Americans and there are many, many Muslim countries who love this country and he has praised Islam as one of the great countries of the world.”

He evidently means Muslims who love this country and that Islam is one of the world’s great religions, but he presses on.

“This proclamation is about what it says it’s about: Foreign policy and national security,” Francisco says. “And we would ask that you reverse the court below.”

And with that, arguments for the day, and the term, come to a close.