A “view” from the courtroom: Judicial restraint

on Mar 26, 2018 at 4:01 pm

The first case for argument in the Supreme Court this morning has a very interesting underlying issue: whether a policy of shackling all criminal defendants at pretrial appearances in a federal district court is constitutional.

But as United States v. Sanchez-Gomez comes before the justices, the questions presented are more procedural in nature, including whether the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit had the authority to review the “interlocutory” appeal of a group of detainees after the federal district court upheld the U.S. Marshals Service restraint policy in the Southern District of California, which is based in San Diego.

A reporter colleague says before the argument that he doubts that the word “shackling” will even come up. This reminds me of the 2015 case of Kimble v. Marvel Entertainment LLC, an intellectual-property dispute over a Spiderman toy in which the superhero was not mentioned even once during a legally dense oral argument (though Spiderman did make a playful cameo in Justice Elena Kagan’s eventual opinion in the case).

Spiderman will not be mentioned once during today’s argument in Sanchez-Gomez, either. But it doesn’t take long for the justices to at least touch on the underlying issue of the shackling policy.

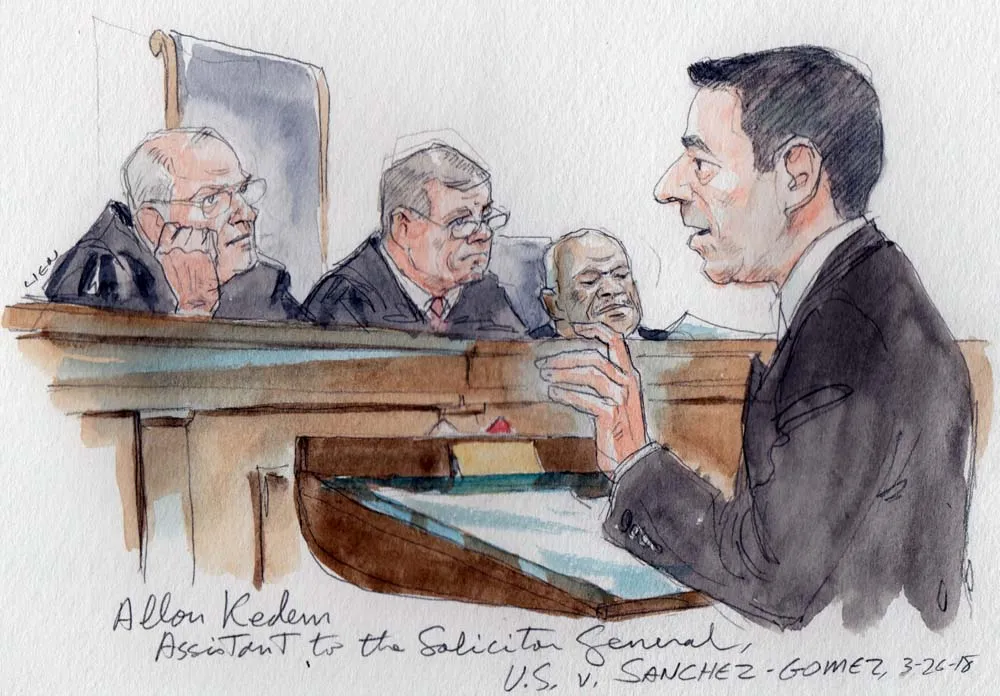

“It seems to me there may well be a legal violation in shackling people, particularly people with disabilities and so forth, and that doesn’t have anything to do with the trial,” Justice Anthony Kennedy says to Allon Kedem, an assistant to the U.S. solicitor general who is arguing, among other things, that the shackled detainees could have challenged the practice as part of an appeal of their criminal convictions.

Allon Kedem, assistant to the U.S. solicitor general (Art Lien)

To be clear, the so-called five-point-shackling policy, which involves handcuffs, leg irons, and chains, is used only in pretrial proceedings, not in a jury trial. As Justice Stephen Breyer put it in his 2005 opinion in Deck v. Missouri: “The law has long forbidden routine use of visible shackles during the guilt phase; it permits a state to shackle a criminal defendant only in the presence of a special need.” (Deck went on to hold that the Constitution bars the use of visible shackles in the penalty phase of a capital trial, absent a special interest.)

The challengers contend they have a due process right to appear unshackled before a judge. But here they are defending their victory in the 9th Circuit, which held both that it could hear the appeal because the challengers essentially brought a class action-like claim covering a widespread policy and that their claims were not moot even though the four had resolved their criminal cases.

Kedem is facing off this morning against Reuben Cahn, the head of the federal defenders’ office in San Diego. Cahn is representing the challengers, who include an Iraq war veteran charged with making an interstate threat, a woman charged with a drug offense, and two aliens charged with immigration-related offenses.

Watching Kedem, who is essentially acting as a federal appellate prosecutor today, go up against Cahn, a federal public defender,reminds us of “For the People,” the new ABC legal drama that premiered this month from “Grey’s Anatomy” and “Scandal” producer Shonda Rhimes.

The network promotes the show this way: “Talented young lawyers work on opposite sides of the law handling the most high-profile and high-stakes federal cases in the country. In the new Shondaland series, these young lawyers will be put to the test both personally and professionally as their lives intersect in and out of America’s most prestigious trial court.”

That court is the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, in Manhattan, which ABC says is “a.k.a. the ‘Mother Court’.” Those talented young lawyers are new hires in the U.S. attorney’s office, on one side, and the federal defender’s office, on the other.

Of course, neither Kedem nor Cahn quite qualifies as a fresh-faced “new hire.” Kedem is a former Kennedy and Kagan clerk who has argued multiple cases as an assistant to the solicitor general. Cahn has been the executive director of the Federal Defenders of San Diego since 2005 and has argued before the Supreme Court at least once before, in a 2011 case.

The justices and their cadres of four TV writers — er, law clerks — have come up with some tough questions for each side.

Breyer asks Kedem about an “absolutely hypothetical” courtroom security policy in which “people will come in bound and gagged in body armor, hung upside down. Okay, you’re saying even if that’s so, that person in this country has no way of challenging that order?”

Kedem says that would be an abuse of discretion and challengers to such an extreme policy could get a writ of mandamus striking it down. But he pushes back on Breyer’s premise, pointing out that the standard use of restraints is “a practice in roughly half of the U.S. Marshal field offices. Other field offices use leg restraints at initial hearings. So I don’t want to accept the premise that this is something truly exceptional.”

If Kedem comes across as the strait-laced, able Washington lawyer for the prosecution, Cahn has a bit of a Southern California vibe in his voice and manner.

“We believe the courtroom really is a sacred space,” he says, sometimes sticking his hand in his pocket and swaying back slightly from the lectern. “We believe judges control that space and assure that individuals come before the court with dignity and with autonomy and with their liberty interest protected, and that there was a well-established right at common law that, under this court’s precedent, is incorporated in the Due Process Clause to appear before courts free of bonds.”

Cahn mentions the notorious Newgate prison in London, where for centuries detainees faced “terrible conditions, shackled hand and foot, and without question, their bonds would be struck off for their arraignments.”

Chief Justice John Roberts tells Cahn there is a “countervailing interest.”

“Which, of course, is the safety of those in the courtroom and the safety of the judges,” Roberts says. “And your scenario of the person coming in from Newgate, I understand, that’s one individual. Here, according to the record from the marshals, you have many situations where there are a lot of people and the idea that [judges are] going to undertake an individualized determination in every case is just something that they don’t have the resources or time for.”

For a case in which the justices specifically declined to take up the constitutional question of whether the shackling at issue violates the Constitution, the argument over the procedural questions provides a pretty good hour of drama.

Unlike during a television show such as “For the People,” there is no time-editing to propel us to the outcome of the case. For that, we’ll have to tune in sometime later this season, probably in June, at 10 a.m. Eastern time/9 a.m. Central. Check your local listings.