Argument analysis: Still no clarity on partisan gerrymandering

on Mar 28, 2018 at 2:28 pm

The Supreme Court heard oral argument today in a challenge to Maryland’s 6th congressional district, which stretches north and west from the Washington, D.C., suburbs. For two decades, the predominantly Republican district was represented in Congress by Republican Roscoe Bartlett, but in 2011, redistricting altered the political composition of the 6th district; the following year, Democrat John Delaney beat Bartlett by over 20 percentage points. The plaintiffs in the case live in the 6th district and contend that Democrats in Maryland engaged in partisan gerrymandering – that is, drawing a redistricting map to favor one political party at the expense of another – to retaliate against them for their past support of Republican candidates like Bartlett. And that, they argue, violated their First Amendment rights of speech and association. Maryland officials deny that any gerrymandering occurred. But even if it did, they maintain, courts should stay out of these kinds of First Amendment retaliation claims because there are no manageable standards for them to use to determine when partisan gerrymandering goes too far. After an hour of oral argument this morning, it was hard to say where the justices are headed, on either this case or partisan gerrymandering more generally.

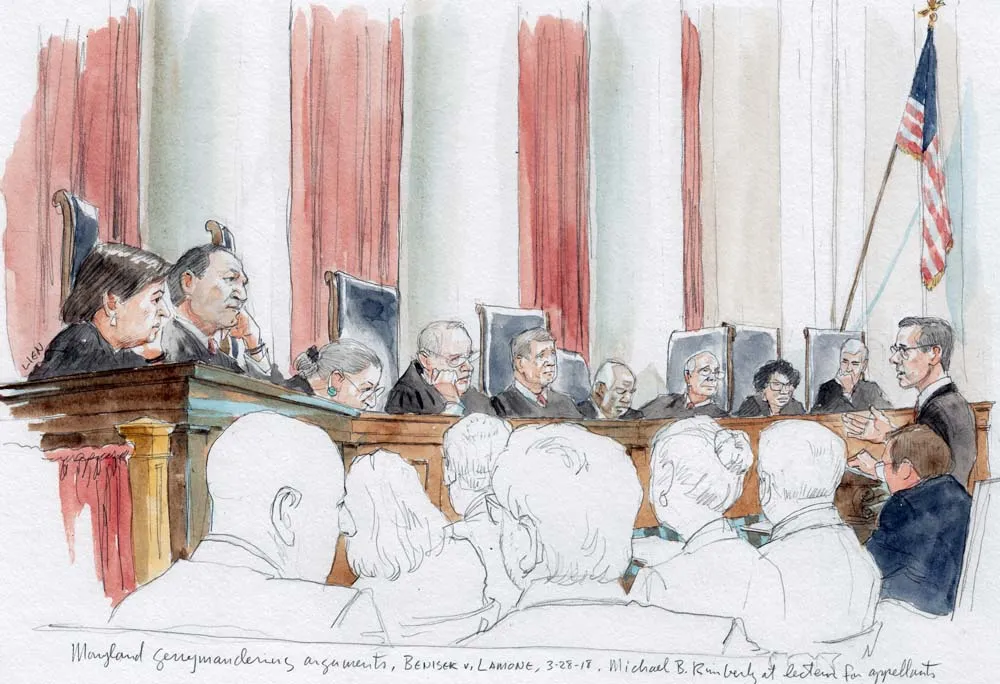

Michael B. Kimberly at lectern arguing for appellants (Art Lien)

The issue of partisan gerrymandering and what (if anything) to do about it has bedeviled the justices for years – as today’s oral argument once again demonstrated. In 2004, a deeply divided Supreme Court declined to step into a dispute over Pennsylvania’s redistricting plan. Justice Anthony Kennedy provided the pivotal vote in the case: He agreed that the Supreme Court should not intervene, while at the same time leaving the door open for courts to review future partisan-gerrymandering cases if a workable standard could be found. And last October, the justices heard oral argument in a partisan-gerrymandering challenge to the statewide redistricting plan enacted by Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled legislature. Although there seemed to be a fairly broad agreement in the Wisconsin case that partisan gerrymandering is, as Justice Samuel Alito indicated, “distasteful,” there was no apparent consensus beyond that. Two months later, the justices announced that they would also review the Maryland case, known in the Supreme Court as Benisek v. Lamone.

If spectators had hoped that today’s oral argument might shed some light on how the justices had voted on the Wisconsin case, they were – unless the justices have excellent poker faces – largely disappointed. Instead, it seemed entirely possible that the justices were counting on the oral argument to give them new insight into a solution to the thorny problem of partisan gerrymandering. But before they even got that far, justices of all ideological stripes expressed doubt about whether they should rule on the partisan-gerrymandering question at all when the case came to them as a request for preliminary relief, rather than for a decision on the merits, and their ruling would come too late for any changes to the state’s congressional maps before the upcoming 2018 election.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the justice most likely to pay attention to procedural issues, kicked off the questioning. She asked attorney Michael Kimberly, who argued for the challengers in the case, how his clients would be irreparably harmed if preliminary relief were not granted when nothing would happen to the 6th district until 2020.

Michael B. Kimberly for appellants (Art Lien)

Justice Sonia Sotomayor chimed in, telling Kimberly that his clients had waited “an awful long time” to bring their lawsuit.

Chief Justice John Roberts then joined the fray, noting that several elections in the redrawn 6th district been held before Kimberly’s clients challenged the map. If the challengers were “willing to let go” of the earlier elections, he suggested to Kimberly, doesn’t that mean that they would not be irreparably harmed if the 2018 election went forward under the existing map?

When the justices did eventually turn to the question of partisan gerrymandering itself, the concern at the heart of the Wisconsin case resurfaced: How should courts evaluate claims of partisan gerrymandering? As Justice Samuel Alito stressed to Kimberly, the Supreme Court has recognized that redistricting is an inherently partisan process, and that a desire to give the party in power an advantage is not, standing alone, problematic.

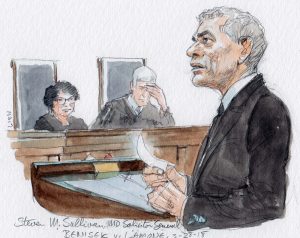

Moreover, there was no obvious consensus among the justices on how courts should determine when politics has played too strong a role in redistricting. Sotomayor and Justice Elena Kagan clearly believed that, under any standard, the 6th district would fail because of the “strong evidence” that Maryland officials had indeed engaged in partisan gerrymandering. Kagan told Maryland solicitor general Steven Sullivan that even if the state is correct and the challengers have not “shown how much is too much” – that is, come up with a workable standard – “however much you think is too much, this case is too much.” Everyone was very upfront about what they were doing, Kagan observed: The 6th district went from being 47% Republican and 36% Democrat to exactly the opposite. How much more evidence of partisan intent do we need, Kagan asked?

Steven M. Sullivan, Maryland solicitor general (Art Lien)

Justice Stephen Breyer, however, was not ready to join Kagan in declaring the 6th district a partisan gerrymander, without more. That won’t solve the other cases, he emphasized. And going forward, he noted, courts won’t have such clear evidence of the officials’ intent, because mapmakers “aren’t stupid.” How, he asked, do we deal with the broader problem of partisan gerrymandering?

Breyer proposed a solution: The court should hold reargument not only in the Maryland and Wisconsin partisan-gerrymandering cases, but also in the North Carolina partisan-gerrymandering case that is currently on hold for the first two cases. He characterized the three cases as presenting “slight variations” on the same theme, in the sense that there is a constitutional violation – partisan gerrymandering – and the Supreme Court has been asked to provide a practical remedy that won’t result in the courts getting pulled into each and every redistricting dispute. Holding simultaneous reargument in all three cases, he suggested, would allow the justices to review all of the theories in the cases (not to mention the pros and cons of those theories) at once. Breyer’s colleagues on the bench, though, didn’t seem to share his enthusiasm for the idea of reargument.

Kagan later pushed back against Sullivan’s contention that allegations of partisan gerrymandering are simply too complicated for courts to resolve. Courts regularly review allegations of racial gerrymandering, which she characterized as involving many similar considerations but “harder circumstances.”

Sullivan was unconvinced, but – much more importantly – so was Roberts, who distinguished between allegations of racial and partisan gerrymandering: The court has recognized that some degree of partisanship is acceptable in redistricting, he reiterated, but it has never said the same for racial discrimination.

During his final moments at the lectern, Kimberly pleaded for “guidance” from the justices. Referring back to the Wisconsin case, in which Roberts worried aloud that most people will interpret a decision in a partisan gerrymandering case as a ruling for the prevailing political party because they won’t understand how the court arrived at its result, Kimberly depicted the dilemma as an easy one. “When plaintiffs succeed in proving that mapdrawers have succeeded in rigging an election, they ought to be entitled to relief.” There may well be five justices on the Supreme Court who agree with him in principle, but today’s oral argument once again demonstrated why the issue of partisan gerrymandering has vexed the justices for so long.

This post was originally published at Howe on the Court.