A “view” from the Courtroom: A final bite at the apple

on Jun 27, 2016 at 3:48 pm

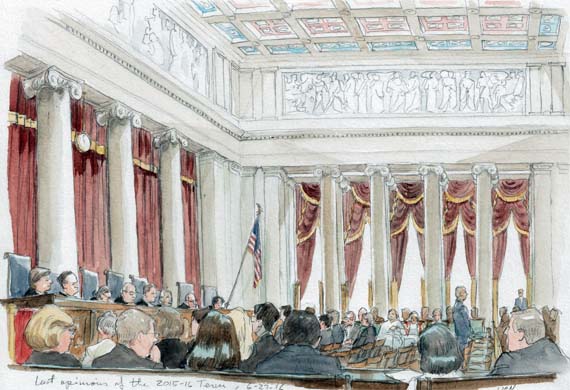

We’re down to the last day of the Term. Outside the Court building, loud demonstrators have taken to the sidewalk in anticipation of the abortion decision. But inside the courtroom, all is cool and even serene.

The public gallery is full, except for some seats between the columns that will be filled with a lucky last group of spectators just before the Justices take the bench. The bar section, as is often the case in the final days of the Term, is not full at all.

Wide-shot of courtroom on last day of opinions, October Term 2015 (Art Lien)

The real action is in the VIP section. Art Lien, court artist extraordinaire for NBC News and SCOTUSblog, points out to me that Judge Emmet G. Sullivan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia is in the section. (Lien has been in his courtroom many times.) Sullivan is involved in any number of high-profile cases, including the matter of Hillary Clinton’s State Department e-mails, so worlds are colliding. We don’t know why he is here to observe today.

Joanna Breyer, the wife of Justice Stephen G. Breyer, is here again today. She is followed into the section a few minutes later by Jane Roberts, the wife of Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. In the front row of the VIP section, three longtime Court employees who are retiring, or recently retired, get to sit in the big comfy chairs, in one of the Court’s nicer traditions. The Chief Justice will recognize them at the end of the morning.

At 9:55 a.m., retired Justice John Paul Stevens gently bounds into the courtroom. He has his cane, but doesn’t seem to need it this morning. He takes a seat next to Reporter of Decisions Christine L. Fallon, who is always in the Courtroom as the Justices perform the part of their job that she is charged with facilitating: the dissemination of opinions.

One person who is not here today, unless he is wearing a very good disguise, is former Gov. Robert F. McDonnell of Virginia.

When the Justices take the bench, the Chief Justice announces that Justice Elena Kagan has the opinion in Voisine v. United States. (For at least the second time on a Monday this Term, Roberts forgets to mention from the bench the traditional statement that “today’s orders of the Court have been duly entered and certified, and filed with the Clerk.” Nevertheless, they were.)

Kagan explains that Voisine is about whether misdemeanor assault convictions for reckless assault, as contrasted with knowing or intentional assault, trigger a federal ban on firearms possession for any person convicted of a crime of domestic violence.

She gives a short lesson on the distinctions between intentional, knowing, and reckless “mindset” for assault, and she explains that the Court has already held that the first two categories trigger the gun possession ban. To explain why the Court is holding today that reckless behavior also triggers the ban, she briefly provides the example from her written opinion of the “person who throws a plate against the wall,” with his wife standing nearby, with a shard of the plate ricocheting and injuring the wife.

Congress’s definition of a “misdemeanor crime of violence” has no exclusion for convictions based on such reckless behavior, she says.

Justice Clarence Thomas has dissented, joined in part by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. There is a pregnant pause, so to speak, as we wait briefly to see if Thomas will dissent from the bench. Thomas was so concerned about this case’s implications for gun rights that during oral argument, he asked a question for the first time in more than ten years. (Not to mention several follow-up questions.)

But Thomas remains silent. The Chief Justice moves on to say that Justice Breyer has the opinion of the Court in Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the case about Texas restrictions on abortion clinics. People in the public gallery perk up a bit.

“We here consider the constitutionality of two statutory provisions of Texas law, which regulate facilities where abortions are performed,” Breyer says. He describes the challenged requirements, which require that physicians at abortion clinics have admitting privileges at a hospital within thirty miles of the facility, and that “minimum standards for an abortion facility must be equivalent to” the state’s standards for “ambulatory surgical centers.”

Breyer doesn’t play it too coy, announcing pretty quickly that these requirements “are not consistent with the constitutional standards set forth” in the Court’s 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, “and we hold both provisions unconstitutional.”

“Wow,” says a young woman in the front row of the public gallery, in a loud whisper.

Breyer delves into the ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit that, because these challengers had already brought a facial challenge to the provisions, their new, as-applied challenge was barred by principles of res judicata. Breyer says that is “a legal doctrine that says, in essence, that you only get one bite at the same apple.”

Breyer says that this case isn’t really the same apple because, as the Restatement of Judgments points out, “material operative facts occurring after the decision” in a first cause of action may provide a “basis for” a new action, even where the action in other respects resembles the first.

He has more to say about this, and we will hear more about res judicata this morning from the dissenting side. But soon enough Breyer moves to the merits.

“We find adequate legal support in the record for the district court’s conclusion that the admitting-privileges requirement imposes an ‘undue burden’ on a woman’s right to have an abortion.” He points out that while the purpose of the requirement is to ensure that women have easy access to a hospital in the case of complications, the district court found abortion procedures in Texas to be “extremely safe.”

Breyer points to the district court’s finding that when the state began to enforce the admitting-privileges requirement, the number of facilities providing abortions dropped from about forty to about twenty.

“The closures mean fewer doctors, longer waiting times, increased crowding, and significantly greater travel distances, all of which, when taken together, burden a woman’s right to choose,” he said.

The ambulatory-surgical-centers standard for abortion facilities also imposed an undue burden, Breyer says, because under Texas law such facilities were already required to meet a host of health and safety standards. The surgical-center provision calls for facilities to meet many extra requirements, but the district court found the requirements will not provide women with better care or more frequent positive outcomes.

He gets into the mathematics of safety rates for abortion procedures as compared with childbirth, colonoscopies, and liposuction, all of which have higher mortality rates yet which Texas permits to take place at home or in a doctor’s office.

Breyer announces the line-up, with Justice Anthony M. Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg joining Sotomayor and Kagan in his opinion (with a concurrence by Ginsburg). Thomas has filed a dissent for himself, while Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. has filed a dissent joined by Roberts and Thomas.

Alito speaks up for his second dissent from the bench in as many court sessions. (Last Thursday, he read at length from his dissent in Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin.)

He starts with res judicata, or “claim preclusion” as it is known in modern terms, he tells us. He acknowledges that it is a “dry legal doctrine” but an important one.

“If we did not have that rule, litigation would never end,” Alito says. The majority’s interpretation of it means litigants will follow a mantra of “If at first you don’t succeed, sue, sue again.”

He has more. “The doctrine of res judicata predates the founding of this country,” Alito says. “That’s why it’s in Latin.”

This brings some chuckles from a crowd that has been pretty silent up to now.

Alito makes his second big point about the severability clause of the Texas statute, saying the majority has run roughshod over it. For example, many of the law’s innocuous requirements that abortion facilities meet the standards for ambulatory surgical centers (though he first says “ambulatory circular centers” before correcting himself) could easily be severed and kept in place.

For example, a requirement that patients be treated with “respect, consideration, and dignity,”—“That’s gone,” Alito says.

The requirement that facilities have fire alarms and emergency communications: “That’s gone,” he says.

One requiring the elimination of slip-and-fall hazards: “Gone,” he says.

“This is an abuse of our authority,” Alito says.

“When we decide cases on particularly controversial issues, we should take special care to apply settled procedural rules in a neutral manner,” Alito concludes. “The Court has not done that here. I therefore respectfully dissent.”

Chief Justice Roberts announces that he has the opinion in McDonnell v. United States. Based on the tenor of oral arguments in late April, when Roberts led the Court’s skepticism of the government’s prosecution of the former Virginia governor, no one is surprised by this opinion assignment.

“Now, there is no doubt the facts of this case are tawdry,” Roberts says, though only hinting at the background about a businessman’s gifts of expensive watches and designer clothing to McDonnell and his wife, Maureen (who was also convicted of federal corruption charges, but whose appeal is not before the Justices in this case). The businessman, Jonnie Williams, was hoping that the state’s universities would conduct research studies on a nutritional supplement made by his company.

The Chief Justice explains the Court’s concern about the government’s expansive interpretation of “official acts.” He cites the Court’s 1999 decision in United States v. Sun Diamond Growers of California, a decision that rejected a broad interpretation of public corruption statute dealing with gifts to public officials.

The opinion “by our late colleague Justice [Antonin] Scalia” made clear that it was not an official act for the president to host a championship sports team at the White House, or the Secretary of Education to visit a high school, or the Secretary of Agriculture to deliver a speech to farmers on agriculture policy and receive small gifts such as a replica jersey, a hat, or a free lunch.

“Hosting an event, setting up a meeting, or giving a speech is not, standing alone, an official decision or act,” Roberts says.

Deputy Solicitor General Michael R. Dreeben, who in April had made the government’s arguments defending McDonnell’s conviction and calling for the more expansive outlook on official acts and corruption, is at the counsel’s table just a few feet away from the bench. (It was Dreeben’s one-hundredth argument, which Roberts recognized with a special tribute at the end of that day.)

“Conscientious public officials arrange meetings for constituents, contact other officials on their behalf, and include them in events all the time,” Roberts says. “The whole notion underlying representative government assumes that public officials will hear from their constituents and act appropriately on their concerns—whether it is the union official worried about a plant closing or the homeowners who wonder why it took five days to restore power to their neighborhood after a storm.”

“The Government’s position could cast a pall of potential prosecution over these relationships if the union had given a campaign contribution in the past or the homeowners invited the official to join them on their annual outing to the ballgame,” the Chief Justice says. “Officials might wonder whether they could respond to even the most commonplace requests for assistance, and citizens with legitimate concerns might shrink from participating in democratic discourse.”

“There is no doubt that this case is distasteful,” Roberts continues. “It may be worse than that. But our concern is not with tawdry tales of Ferraris, Rolexes, and ball gowns. It is instead with the broader legal implications of the Government’s boundless interpretation of the federal bribery statute. A more limited interpretation of the term ‘official act’ leaves ample room for prosecuting corruption, while comporting with the text of the statute and the precedent of this Court.”

Roberts announces that the decision vacating McDonnell’s conviction and remanding his case is unanimous.

The Chief Justice then launches into the traditional closing “ceremonies.”

“I am authorized to announce that the Court has acted upon all cases submitted to the Court for decision this Term,” he says. “Disposition of items scheduled for conference today will be reflected on an Order List that will be released at 9:30 tomorrow morning.”

“The Court will be in recess from today until the first Monday in October 2016, at which time the October 2015 Term of the Court will be adjourned, and the October 2016 Term of the Court will begin, as provided by law.”

He then thanks Court employees for their “outstanding work and dedication,” and the members of the Supreme Court Bar for their “professionalism and cooperation.”

He next recognizes the three retiring Court employees who have been sitting in the VIP seats. Special Agent Gilbert Shah is retiring after twenty-five years of service on the Supreme Court Police force; Elizabeth Brown, a former assistant clerk for judgments, retired late last year after twenty-six years of service; and Sheila Rogers retired last November as a telephone operator after thirty-three years at the Court.

Ms. Brown shouts a “thank you” back at the Chief Justice just as Marshal Pam Talkin bangs her gavel to end the session, and the eight members of this Court disappear behind their curtain with this sometimes tragic, sometimes disjointed Term behind them.