Argument preview: Warrantless DUI tests and the Fourth Amendment

on Apr 15, 2016 at 9:44 am

In 2012, North Dakota had the highest per-capita rate of deaths attributable to drunk driving in the United States: 11.3 deaths per 100,000 people, more than three times the national average. Many of the drivers arrested for driving under the influence in the state – nearly one in five in 2011 – refused to take any test that would allow police to measure the alcohol in their blood, making it harder to bring criminal drunk-driving charges against them. In an effort to cut down on drunk driving in the state, North Dakota legislators passed a law that imposed criminal penalties on suspected drunk drivers who declined testing. North Dakota says this strategy – which is similar to laws in eleven other states, including Minnesota, and on National Park lands – has worked and is now an important weapon in the fight against drunk driving.

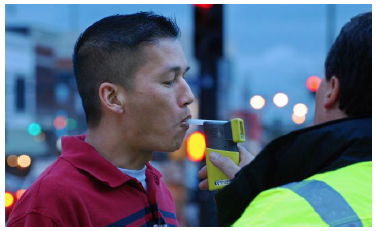

But drivers who have run afoul of the test-refusal laws see the law very differently: not only is it a violation of their Fourth Amendment rights to be free of unreasonable searches, they say, but there are other, even more effective ways to curb drunk driving. Three of those drivers will make their case next week at the Supreme Court, which will consider whether states can, in the absence of a warrant, make it a crime for a suspected drunk driver to refuse to take a blood or breath test.

In 2012, William Bernard was arrested on suspicion of driving while impaired. Bernard had come to the attention of the Dakota County, Minnesota, police when a truck became stuck while trying to pull a boat out of the water. Bernard – who was wearing only his underwear – denied that he was the driver of the truck, but he was holding the keys to the truck in his hand; moreover, witnesses told police that Bernard, who admitted that he had been drinking, was in fact the driver. When Bernard refused to take a breath test, he was charged with violating the state’s test-refusal law.

The following year, Danny Birchfield of North Dakota found himself in a similar predicament. After he drove his car off the road, Birchfield failed a field sobriety test. When a preliminary breath test suggested that Birchfield’s blood-alcohol concentration was well over the legal limit, he was arrested, but he refused to allow his blood to be tested. Like Bernard, that refusal led to criminal charges against him. Birchfield pleaded guilty but reserved the right to appeal: among other things, he was sentenced to thirty days in jail (with twenty of those days suspended) and one year of unsupervised probation, and he was ordered to pay fines and court fees totaling $175.

A third driver, Michael Beylund of North Dakota, consented to a blood test after being told that he would otherwise face criminal penalties, leading to the suspension of his driver’s license for two years.

As the end of April approaches, it seems only fitting that the facts and arguments before the Court bear more than a passing resemblance to a law school exam, drawing on several different strands of the Court’s case law. All sides start from common ground: the Fourth Amendment allows a search only in two scenarios: when law-enforcement officials have a warrant (which, there is no dispute, none of the police officers in this case did), or when one of several recognized exceptions to the warrant requirement applies.

The Minnesota Supreme Court relied on one such exception, for “searches incident to arrest,” to uphold the charges against Bernard. It reasoned that the exception allows police officers to conduct a full-body search of an arrestee, which would include requiring the arrestee to take a breath test without a warrant. And if the arrestee can be required to take the breath test without a warrant, the thinking goes, the state can also make it a crime to refuse the test.

Bernard (who is represented by the same attorneys as Birchfield and Beylund) contends that the Minnesota Supreme Court got it all wrong: the search-incident-to-arrest exception does not apply to his case. The U.S. Supreme Court’s Fourth Amendment cases, he argues, make clear that the rationale for the exception rests on two rationales only: to protect the arresting officers and guard against destruction of evidence. Neither of those rationales are implicated here, he maintains: once a suspected drunk driver has been arrested, his breath does not pose any danger to the arresting officers, and he can’t change or otherwise destroy the alcohol content of his blood. The state court’s ruling, he adds, also is difficult to reconcile with McNeely v. Missouri, a 2012 case in which the Court rejected a bright-line rule that would allow blood tests of suspected drunk drivers without a warrant under an exception for “exigent circumstances.”

Minnesota echoes its state supreme court’s reasoning on this point. Over forty years ago, it insists, the Court’s decision in United States v. Robinson “created a categorical rule holding that police officers are authorized to conduct a full search of a person who has been lawfully arrested.” That ruling, it argues, allows both a warrantless breath test for a suspected drunk driver and criminal charges for refusing to take the breath test. And, the state continues, the breath tests do advance the rationale of preventing the destruction of evidence: even if the Court in McNeely ruled that alcohol does not disappear from the bloodstream so quickly to justify warrantless blood tests in all cases, the Court in that case “did not dispute” that blood-alcohol levels decline as time passes.

North Dakota defends its test-refusal law on the ground that there is no search, much less a search without a warrant. Rather, it argues, a driver on the state’s roads is deemed to have consented to the blood test; the law merely criminalizes the refusal to take that test. The drivers counter that states can’t make a benefit like driving contingent on giving up a constitutional right. There is no reason, they say, to believe that drivers “understand that they have granted consent to be tested simply by virtue of driving in North Dakota.” This is particularly true, they contend, in a large, car-dependent state like North Dakota, that has little in the way of mass transit; driving is an essential part of residents’ lives.

But there is no bright-line rule that prohibits the government from ever putting any conditions on the exercise of constitutional rights, the state retorts. Rather, the federal government adds in its brief supporting the states, the test is whether the government is asking someone to surrender a constitutional right to obtain a benefit that “has little or no relationship to the condition imposed.” That is not the case here, the government contends, because there can be no serious argument that “a test of whether a driver poses a danger to others on the road somehow lacks a nexus to driving privileges.”

The states add that their test-refusal laws can still survive for another reason: the Fourth Amendment only bars unreasonable searches and seizures, and the chemical tests in this case are reasonable. Whether a search is reasonable, Minnesota contends, hinges on whether the government’s interests in the search outweigh the intrusion on the privacy of the individual subject to the search. Here, Minnesota argues, the government’s interest in protecting the public and prosecuting drunk drivers is substantial. By contrast, it asserts, the breath test is only “minimally intrusive” – essentially requiring the suspect to blow into a straw for four to fifteen seconds – and measures only the arrestee’s blood-alcohol level, without disclosing any other facts about the driver. Moreover, drunk drivers have relatively few expectations of privacy either while they are driving on a public road or in police custody. And the sweep of the law is narrow: it applies only to drivers whom the police have probable cause to believe are drunk.

As Fourth Amendment expert Orin Kerr noted recently, this case is “like a game of ‘whack-a-mole‘” for the drivers challenging the test-refusal laws: they have to convince at least five Justices that none of the justifications for the laws offered by the states are correct; if the states are right on at least one ground, then they can prevail. Given how common the test-refusal laws are, this is sure to be a case that lawyers, legislators, and law-enforcement officials will all be watching closely.