A “view” from the Courtroom: The Justices return to a black and gray bench

on Feb 22, 2016 at 3:59 pm

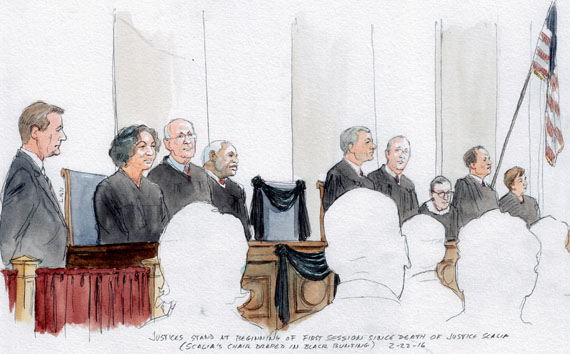

The Supreme Court returned to the bench on Monday for the first time since the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.

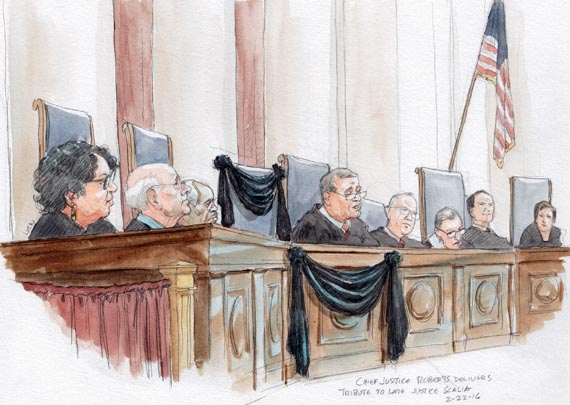

“The memorial drapery on the Bench and chair beside me signifies mourning for a Justice who has died in active service on the Court,” Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., said as he and his seven remaining colleagues took to that bench. “Today, it marks the loss of our friend and colleague, Antonin Scalia, who died unexpectedly on February 13, 2016.”

Justices stand at beginning of first session since Scalia’s death. Black bunting adorns the bench and Scalia’s chair. (Art Lien)

The memorial drapery was attached in the days after Justice Scalia was found dead at a ranch resort in West Texas. It will remain in place until March 14, thirty days after his death.

Roberts recounted key aspects of Justice Scalia’s biography – his birth in 1936 in Trenton, N.J., attendance at public grade school in the New York City borough of Queens, a Jesuit military school in Manhattan, his enrollment at Georgetown University in Washington, and attendance at Harvard Law School.

The Chief Justice noted Scalia’s “devoted union” to Maureen McCarthy, and he named all nine of their children: Ann Forrest; Eugene; John Francis; Catherine Elisabeth; Mary Clare; Paul David; Matthew; Christopher James; and Margaret Jane.

Then, Roberts gave the outline of the late Justice’s professional career: private practice in Cleveland; teaching law at the University of Virginia and later the University of Chicago law schools; general counsel of the White House Office of Telecommunications Policy “at the dawn of the cable television age”; and, among other positions, assistant attorney general for the Office of Legal Counsel in the Department of Justice.

“In 1976, during his tenure at the Justice Department, Justice Scalia argued his first and only Supreme Court case,” Roberts said “He prevailed, establishing a perfect record before the Court.”

(The case was Alfred Dunhill of London, Inc. v. Republic of Cuba.)

The Chief Justice noted Scalia’s service on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and his 1986 nomination by President Reagan to the Supreme Court.

“Justice Scalia devoted nearly 30 years of his life to this Court in service to the Country he so loved,” Roberts said, noting that the late Justice wrote 282 majority opinions for the Court. (The last of those was his Jan. 20 opinion for the Court in Kansas v. Carr, an 8-1 decision about sentencing procedures in death penalty cases.)

“He was also known, on occasion, to dissent,” the Chief Justice said, drawing laughter in the Courtroom. (The last of Justice Scalia’s dissents came Jan. 25 in Federal Energy Regulatory Commission v. Electric Power Supply Association. Justice Clarence Thomas joined his dissent from the ruling upholding FERC’s power to regulate wholesale power suppliers.)

Chief Justice Roberts went on, “We remember his incisive intellect, his agile wit, and his captivating prose. But we cannot forget his irrepressible spirit. He was our man for all seasons, and we shall miss him beyond measure.”

Roberts said a traditional memorial service of the Court and the Supreme Court Bar to honor Scalia would be held in the Courtroom “at an appropriate time.”

“And now we turn to the business of the Court,” the Chief Justice said.

That meant bar admissions, and argument in two cases. In the first, Kingdomware Technologies Inc. v. United States, a pall seemed to remain over the Courtroom. That may have been in part due to the arcane nature of the question raised in the case about statutory contracting preferences by the Department of Veterans Affairs for veteran-owned small businesses.

Eventually, the Justices would start peppering the lawyers with questions. Justice Thomas would converse privately with Justice Stephen G. Breyer. (This was also the day when Thomas reached the ten-year mark for not formally asking a question during oral arguments.)

The second argument of the day, in Utah v. Strieff, was much more lively. The question was whether evidence seized incident to a lawful arrest on an outstanding warrant should be suppressed because the warrant was discovered during an investigatory stop later found to be unlawful.

This argument was underscored by recent controversies involving the police and the public, with references to Ferguson, Mo., to police stop-and-frisk practices, to shootings of police officers, and debate over how many people in the country have outstanding warrants for their arrests.

It was an argument that Justice Scalia surely would have jumped into, whether to display his conservative side’s sympathies for law enforcement or his liberal streak — concern that Fourth Amendment protections not be infringed.

Last week, Justice Breyer told an audience at Yale Law School that the Supreme Court is “going to be a grayer place” without Justice Scalia.

Even after the memorial black drapery is removed from the Courtroom next month, and the Justices move into their new seating arrangement, the gray will remain.