Argument analysis: Justices hard to read on Arizona redistricting plan

on Dec 8, 2015 at 5:41 pm

“Where’s the beef?” That was the question from Washington attorney Paul Smith, arguing at the Court today on behalf of the five-member independent commission charged with drawing new state legislative maps for Arizona. The Justices heard oral arguments in a challenge by several Arizona voters to the maps that the commission drew after the 2010 census; the voters allege that the commission violated the principle of “one person, one vote” when it intentionally put too many residents into Republican-leaning districts while putting too few into Democratic-leaning districts. The Court’s four more liberal Justices seemed inclined to agree with Smith, but some of the Court’s more conservative Justices were harder to read. Because a ruling in favor of the challengers could potentially affect redistricting maps around the country, both sides could be on tenterhooks waiting for the Court’s eventual decision.

As I explained in my preview of the case, the first issue before the Court was the role of partisan politics in the creation of the over- and under-populated districts and how courts should determine whether that role crossed constitutional lines. Attorney Mark Hearne, representing Wesley Harris and the other challengers, told the Justices that partisanship was “rank” in the redistricting process. But some Justices were unconvinced, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg telling him that she found it “odd” that he was alleging partisanship when “the end result was that the Arizona plan gave Republicans more than their proportionate share of seats in the state legislature.” If this was, she continued, an effort to “to stack the deck” in favor of Democrats, “it certainly failed.”

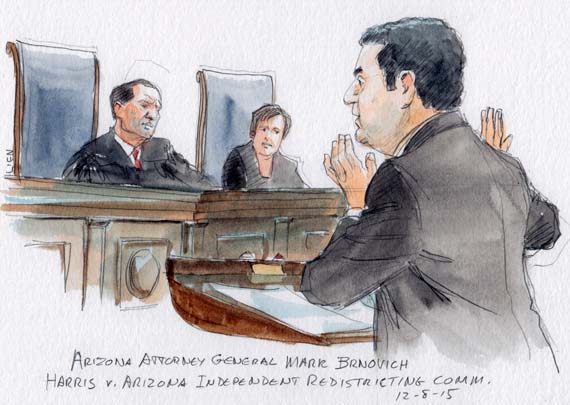

Attorney Paul Smith, representing the independent redistricting commission, painted a very different picture. He asserted that partisanship had played such a “tiny role” in the redistricting process, and its effect was so minimal, that “it’s simply not something that ought to be taken seriously as a constitutional problem.” Justices Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor seemed to agree with him; Breyer suggested that any deviation of less than ten percent from the ideal equal population was “minor,” while Sotomayor emphasized that, if the Court were to rule for the challengers, virtually every redistricting plan in the country would face a vote-dilution challenge. Justice Elena Kagan made a similar point in a question for Arizona attorney general Mark Brnovich, who argued in support of the challengers. Describing a hypothetical in which a state has a policy to respect county lines when drawing districts, even if it will “cause a little bit more deviation on the one-person, one-vote metric,” she asked him whether the “one person, one vote” principle would preclude an intentional decision to draw maps that would increase the deviation from four to five percent, or from seven to eight percent. “Yes,” Brnovich responded, if it was done in “a systematic and intentional manner.”

But Smith’s defense of the districts also met with pushback from some Justices, with Justice Samuel Alito reminding him that the lower court in this case had indeed found that “partisanship played some role” in the redistricting process. And Justice Antonin Scalia referred back to a case from last Term, in which the Court upheld the Arizona commission’s authority to draw federal congressional districts. Observing that the Court had previously been assured that the commission “was going to end partisanship, get politics out of redistricting,” Scalia told Smith that he would “be very upset if . . . there were any motivation of partisanship” and added that he wished “this case had come up” before last Term’s case.

Much of the argument, though, focused on a second question in the case: whether the commission’s desire to comply with the Voting Rights Act and obtain pre-approval (known as “preclearance”) for its redistricting plan from the U.S. Department of Justice justified the deviations from the ideal equal population. Hearne insisted that the commission could have drawn a redistricting map that complied with the VRA and would receive preclearance without over-populating the Republican districts. That assertion found a skeptical audience even among some of the more conservative Justices. Chief Justice John Roberts asked Hearne how confident he actually was that the over- and under-populated districts weren’t necessary to comply with the VRA and obtain preclearance. The preclearance process, Roberts noted, is “fairly opaque.” Scalia added that the commission “thought that they were doing this in order to comply with the Justice Department.” Even if they were mistaken, Scalia continued, “that doesn’t show a bad motive on their part, does it?” Kennedy echoed that thought, telling Hearne that bad legal advice is different from an impermissible motive.

However, later on, some of the same conservative Justices had tough questions for Smith on this issue. Roberts, for example, asked Smith whether “the Justice Department’s procedures can trump the requirements of the Constitution. ” And Scalia threw Brnovich a softball, telling him that Scalia “thought you were saying that it doesn’t matter whether you were doing it to obtain Justice Department clearance. You cannot do something that is unconstitutional.”

Interestingly, none of the Justices addressed the remaining question in the case: whether, even if the commission’s desire to comply with the Voting Rights Act and obtain preclearance might have once justified the creation of unequally apportioned maps, that justification no longer existed because – since the Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder – no state or local government is currently required to obtain preclearance at all. This could cut two ways. On the one hand, because this question only comes into play if the commission wins on the threshold preclearance question, it may signal that the Court’s more conservative Justices are confident that the challengers, rather than the commission, will prevail. On the other hand, it could simply mean that none of the Justices, of any ideological stripes, take the question seriously. We’ll know more when the Court issues its decision – almost certainly sometime next year.