Argument analysis: Looking for limits on frozen assets

on Nov 11, 2015 at 5:41 am

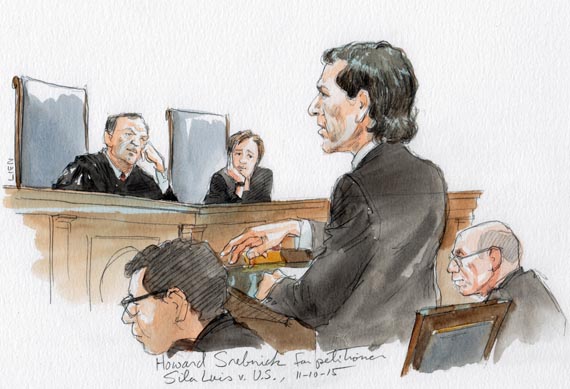

In 2012, Sila Luis was indicted on charges that she had defrauded Medicare by paying illegal kickbacks and billing the federal government for services that the employees of her home health care agency had not actually provided. Yesterday her case was in the U.S. Supreme Court, where she hoped to convince the Justices that a court order freezing all of her assets, including those unrelated to her alleged crimes, violated her Sixth Amendment right to hire and pay the lawyer of her choice to defend her. Luis’s attorney, Howard Srebnick, didn’t seem to be making much headway with his arguments during his first stint at the lectern, but – as it turned out – neither did Deputy Solicitor General Michael Dreeben, who argued on behalf of the federal government. Both sides faced tough questions from the Justices, particularly with regard to the limits of their respective proposed rules, and by the time Chief Justice John Roberts concluded the hour of oral arguments, the case appeared to be too close to call.

During his half-hour before the Justices, Srebnick reiterated that – going as far back as the Founding – the Sixth Amendment has always recognized the right to spend your own money to hire a lawyer. This means, he asserted, that a defendant must be allowed to use the assets that she rightfully owns to pay for her defense.

But Srebnick had to grapple with the Court’s 1989 decision ruling that “tainted” assets could be frozen before trial to ensure that they would be available for forfeiture if the defendant is convicted. As he had in Luis’s briefs, Srebnick maintained that the earlier case was different because no one has a right to drug money, allowing the government to freeze it before trial. By contrast, he told the Court, in this case Luis is the exclusive owner of her “untainted” assets. If she is eventually convicted, he conceded, then the U.S. government may seek money, but it is hers until then.

Justices of all ideological stripes appeared unconvinced. Justice Elena Kagan told Srebnick that there is a “powerful intuition” to his argument, but “it seems that the distinction you’re making is one the Court explicitly rejected in” its 1989 ruling. Your case, she continued, “doesn’t seem to present any different circumstances.” Roberts was also skeptical, telling Srebnick that, “if you can freeze tainted assets without running afoul of the Sixth Amendment, I don’t understand why you can’t freeze untainted assets.”

Justice Samuel Alito seemed to agree. He asserted that, “as a matter of economics and common sense,” “money is fungible.” He described a hypothetical in which twin brothers rob a bank and steal $10,000, which they divide between the two of them. They also each receive $5,000 as a birthday present from a rich uncle. The first twin spends all of his money from the robbery but saves the birthday money, while the second one spends all of his birthday money but saves the money from the robbery. Under Luis’s position, Alito emphasized, the first brother could use his money to hire a lawyer, but the second one couldn’t. “What sense does that make?” Alito asked. Justice Anthony Kennedy chimed in, telling Srebnick: “The law that you want this Court to say is ‘spend the bank robbery money first.’”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg also appeared sympathetic to the government, telling Srebnick that Congress had singled out some crimes – including the health care fraud alleged in this case — for special treatment, and it declined for such crimes to draw a line between tainted and untainted assets. “They seemed to want to come down very hard on these crimes,” she suggested.

The Justices also expressed concerns about how far Luis’s proposed rule would reach. Justice Sonia Sotomayor told Srebnick that the “logic of your argument would suggest that you can’t freeze untainted assets for anything, because the government has no property interest.” Srebnick tried to reassure her that he wasn’t asking the Court to go that far, but she countered that “once we announce a rule, we have to carry it to its logical conclusion.” Sotomayor (herself a former federal district judge) also expressed concern about the practicalities of Luis’s proposed rule, asking Srebnick how the district court can “ensure that” Luis “doesn’t use every penny” for her defense, leaving nothing for the government if she is convicted.

Antonin Scalia also tested the limits of Luis’s rule, describing a scenario in which a defendant is “a devout Muslim” who “makes an annual trip to Mecca every year.” If her assets would otherwise be frozen, Scalia asked Srebnick, “does she have a constitutional right to” access to her money so that she can make the trip? Srebnick tried to distinguish Scalia’s hypothetical, telling him that Luis has “an immediate need for a lawyer”; by contrast, the Muslim woman could wait and go another year. But Scalia appeared unconvinced, telling Srebnick that he didn’t “know how you can limit your principle to the Sixth Amendment.”

Deputy Solicitor General Michael Dreeben, arguing on behalf of the United States, emphasized that the same principle animating the Court’s decision allowing restraints on tainted assets before trial applies equally to untainted ones: if the government can get the money at the end of the day, he told the Court, it needs to be sure that the money will be available. The statute on which the government relied to freeze Luis’s assets, he added, “negates the premise that there is a clean line between tainted and untainted assets.”

But if the Justices were worried about the limits of Luis’s proposed rule, they had similar concerns about how broadly the government’s rule would sweep. Kennedy asked Dreeben to explain what limits the law puts on the government’s ability to freeze assets. If the government wins, he predicted, states could freeze assets for any number of reasons, prevent the private bar from representing them unless they did so on a contingent basis. Kennedy would return to this point again later on, telling Dreeben that the consequence of his position was that any state can freeze assets pending trials for all kinds of offenses, from assault and battery to date rape, even if – as a result – most people cannot afford to hire lawyers. Roberts echoed this thought, telling Dreeben that, on the government’s reading, the asset freezes could “apply to every crime on the books.” Sotomayor weighed in as well, predicting that, if the Court were to rule for the government, in three-and-a-half years Congress will change similar federal laws to allow the government to freeze “untainted” assets before trial in all kinds of crimes, preventing even more defendants from retaining their preferred lawyers.

Kagan acknowledged that the government’s reasoning is “a fair, strong argument” as long as you are “comfortable” with the Court’s 1989 decision allowing courts to freeze “tainted” assets before trial. But she suggested that she might not be. She agreed with Dreeben that “you might be right that it doesn’t make sense to draw a line here, but it leaves you with a situation in which more and more and more we’re depriving people of the ability to hire counsel of choice in complicated cases. And so what should we do,” she asked, “with the intuition that” the 1989 case sent the Court down the wrong path? She also tried to find a middle ground, asking Dreeben whether there is any way to read the statute allowing the untainted assets to be frozen to allow a defendant to spend his assets for his lawyers, but not to meet other expenses. No, was the response.